You are here

Home ›Crisis, Hunger and War: Class Struggle Knows No Borders!

...the focus of the class organisation of the proletariat lies in the International...

Rosa Luxemburg

Billions are being pumped into the swirling financial markets to prop up stricken banking houses and to stem the effects of the crisis. On the other hand, across the world, new programmes of cuts are always being developed, social benefits are being cut, wages lowered and jobs phased out. Now, as before, the world situation is marked by growing polarisation and increasing instability. The crisis in the financial markets, hunger revolts in Haiti, Africa and Asia, global warming, the terrifying implications of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan - there can be no talk of the "end of history" (F. Fukuyama). Even the most eloquent apologists of the "markets' powers of regeneration" are expressing themselves in an increasingly restrained fashion. Admittedly, at first it seems a good laugh when a figure like the head of the Deutsche Bank, Ackermann, calls for state aid to fix the debacle on the finance markets, but, nevertheless, it should be clear who, in the end, will really foot the bill.

War against the Poor

Here, too, following the so-called reform of the social state, the chasm between the rich and the poor has deepened considerably. Since 1992, the incomes of the poor have fallen by 13% relative to prices, while the earnings of the so-called "top earners" have gone up by nearly a third. The tendency towards impoverishment will be further continued by the soaring prices for gas, electricity and food. The middle classes, once celebrated as the backbone of the German model, are trapped inside a process of continual decline. While so-called "experts on the social state" are active in the media, wondering whether child or pensioner poverty is now the biggest problem, companies report record profits. Following the company tax reform, in 2007 corporation tax for profits of listed companies fell from 25% to 15%, just as the taxes on profits and interest and dividends went from 44% to 26%. All in all, therefore, a tax gift of about €10bn! At the same time, under the standard cliché of empty tills, wages were cut, the retirement age increased, working time made longer and jobs done away with...

The tendency towards job insecurity and low wages is also increasing ever faster. In the period between 1994 and 2005, the number of part-time workers went up from 6.5 to 11.2 million. According to a study of Duisberg-Essen University's Institut Arbeit und Qualifikation (IAQ - Institute of Work and Qualification), 6.5 million people belong to the low-wage sector. The proportion of low-paid workers of the total employed was over 22% in 2006. In 1995, it was 15%.

The Return of the Strike

After years of wage sacrifices, many people are fed up. This is shown not least by the train drivers' struggle, the strike movement in public services and the confrontations in the retail trade, in the Berliner Verkehrsbetrieben (BVG - Berlin local transport) (1) and the post. Even if, in these cases, it was primarily a question of defensive struggles, the "new appetite for striking" (Der Spiegel) shows that class confrontation is back. That is worth saluting, but it is not yet a reason for triumphalism. Despite the growing rank and file discontent and dissatisfaction, the unions are still able to control struggles and to keep them small. With consequences which are sometimes devastating: the supposedly so successful GDL (Gewerkschaft Deutscher Lokomotivführer - Union of German Train Drivers) deal turns out to be very modest on closer inspection, and was bought at the expense of totally taking the piss out of the conductors. Just as thin pickings were delivered by the supposed "healthy compromise" in the public services, which obviously was the result of a calculation of how to quickly operate a safety valve. As a result, the comrades from the post and the weak retail sector were at the time fairly isolated in their struggles. In the clash in the BVG too, Ver.di's (2) wheeling and dealing in the negotiations led increasingly to the demoralisation of the workers. If the union leads the strike into a dead end, and it seems at the moment that it will, this will weigh heavily against resistance in other areas of the public services in Berlin.

The Unions: for the Status Quo and against the Working Class!

Trades Unions work well as centres of resistance against the encroachments of capital. They fail partially from an injudicious use of their power. They fail generally from limiting themselves to a guerilla war against the effects of the existing system, instead of simultaneously trying to change it, instead of using their organised forces as a lever for the final emancipation of the working class that is to say the ultimate abolition of the wages system.

Marx, 1865, in Wages, Price and Profit

Today, we can see the absolute failure of the unions to even defend the most basic interests of the workers. Their transformation from "centres of resistance against the encroachments of capital" to a state-supporting bureaucratic apparatus is irreversible. Today, the unions function on the basis of the political acceptance of the wages system and as moments of bourgeois mediation between workers and capitalists. They no longer see themselves as exclusively obliged to improve the working and living conditions of their members, but, on the contrary, primarily to maintain the "status quo", that is, to the smooth functioning of the national economy. Every "leftist" who continually explains the actions of the unions by betrayal by the current leadership, which should be replaced by another, show themselves to be just as naïve as they are idealist. In the end they express a desire, all too frequently disguised as "Leninist", for union posts and state support. Unions betray nothing and no-one, least of all themselves. If they sabotage struggles, take people for a ride and make themselves indispensable for capital as assistants in negotiation and maintaining order, then they are only acting consistently and logically in harmony with their very own concerns, wanting to negotiate the business conditions for the sale of the labour-power commodity with the capitalists as an equal partner. The unions cannot be reformed, "reconquered" or transformed into instruments of liberation! The problem is not simply just one of leadership, it is the form of organisation itself which is based on the politics of letting someone else represent you. This stands against any perspective of greater freedom.

This doesn't mean that we simply call for leaving the union or tearing up the membership card, which would only be on the same level as many of the illusions of co-management fed by the union. The old argument about whether private legal insurance or union membership offers the better protection from the sack and employers' despotism is a debate about false solutions, as long as workers face the boss singly and in an isolated fashion, and hope for protection from "above" in this desperate situation, which mostly ends badly. Nor do we call for the construction of new, better unions, which, sooner or later, would end up just as mired in the politics of representation as the old ones. It is a question of understanding that the unions' legalistic framework, fixated on the national state, is a straitjacket which subjects resistance and militancy to the law of the bourgeoisie. Our aim is that the working class itself should decide on the goals of its struggles and that the organisation of these struggles must remain firmly in its own hands.

Struggle Internationally Instead of Losing Patriotically

In view of the international sharpening of the crisis it is becoming clearer that the unions' stubborn national framework for action is the main obstacle to the defence of our living interests. The Nokia example shows this in great clarity. Thanks to its monopoly of information and its apparatus, the union was in the position to strangle the initial dynamic of the struggle (for example, the spontaneous demonstrations and, especially, the Opel solidarity strike). With gossip about the "emotional coldness" of the Finnish bosses, racist resentment against so-called "Roumanian cheap labour" and patriotic throwing away of mobile phones, the union, the media and the politicians succeeded in bringing the conflict into the nationalist arena. At the end of this spectacle, all we got was paltry compensation and the closure of the works. Anyone who gets involved in this nationalist logic gets caught up in an inescapable competition to undercut wages, a downward spiral into misery. Only with an international strategy is it possible to do something against the continued attacks on wages, working conditions and social rights. All the more important to see local confrontations in an international context, and to free ones vision for the perspective of a class struggle across borders. The racist prejudice, stirred up by union bigwigs and politicians, of supposedly pliant Roumanian low-paid workers was impressively refuted by the strike of the Dacia workers. A conflict which, in the meantime, has also encouraged other sectors of the Roumanian working class to struggle. In the same vein, there have been strikes in Poland and Bulgaria against wage cuts. Without waiting for an eventual union announcement, workers in the FIAT factory in Pomigliano (Southern Italy) started a spontaneous strike to defend themselves against a bosses manoeuvre to lay them off (see articles in this issue). In Egypt, confrontations in the textile industry have lead to real mass strikes. All in all, a movement, which, in combination with protests against rising food prices, could take on a special dynamic...

For Communism!

The fact that these and other struggles have taken place is without doubt encouraging. Nevertheless, by themselves they will at best remain isolated episodes of resistance, if they do not succeed in pushing back bourgeois ideologies and opening up a perspective which goes further. The task of revolutionaries consists of keeping the overall interest of the working class in mind, supporting its struggles, criticising limitations and seeking to strengthen the wage-workers' consciousness of, and trust in, their own power. Revolutionary politics develops when revolutionaries are in the position to learn from workers in struggle, to generalise experience of struggle and to carry consciousness and perspectives to the movement. This demands an organisational framework. In our understanding, this can only be a political structure, an international and internationalist revolutionary organisation. International, because capitalism can only be fought and overcome on a world scale; internationalist, because the rejection of every nationalist ideology is the basic pre-condition for the production of class unity; revolutionary, because it is only in a radical break with capitalism that the perspective of living not just in conditions fit for human beings, but as human beings. The construction of such an organisation, the international regrouping and unification of revolutionaries in a new communist world party will be a long and difficult process. But it is necessary, in order to replace bourgeois society with its wars, crises, classes and class contradictions by an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

For a stateless, classless society!!

Gruppe Internationaler SozialistInnen (www.gis.de.vu)(1) See German Train Drivers' Fight to Avoid Isolation in _Revolutionary Perspectives 44 and Striking is the Only Language the Bosses' Understand!_ in_ Revolutionary Perspectives 45.

(2) Vereinte Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft - United Service Union .

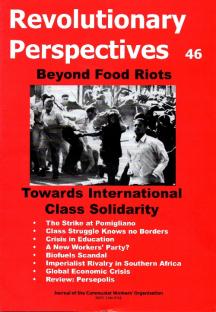

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #46

Summer 2008 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.