You are here

Home ›Lomov's Economic Notes

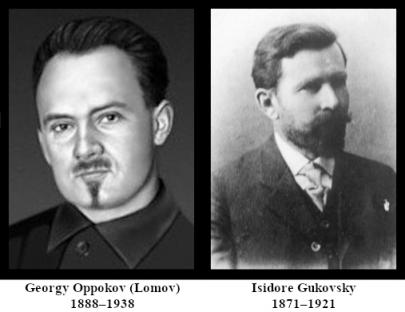

We have already introduced readers to Afanasi Lomov (Georgy Oppokov) when printing the first of his “Economic Notes” which appeared in Kommunist No.1 [see leftcom.org]. This is the second such document which he wrote for Kommunist No.2 and, like the first, it is an attack on the conservative financial policies of the Bolshevik Right in the person of the People’s Commissar for Finance, Isidore Gukovsky [more on him can be found in the already-cited article and in the critique of him by Ossinsky in the same issue, see: leftcom.org].

A tedious-looking discussion about “financial reform” is, at first sight, hardly likely to quicken the pulse of readers. However the issue that the article raises is a much deeper and more important one. It reveals a real problem of an isolated workers’ revolution which has overthrown capitalist power. Do the workers simply administer the existing state of affairs until the rest of the world working class join them so that a real transformation of economic and social relations take place, or, do they begin that process by at least starting on the road to transforming society in the direction of communism? The Russian Revolution took the working class into uncharted territory where there was no easy political map or Google app to guide them.

Contrary to what their critics often argue, the Bolsheviks had no preconceived notions on the matter. As Steve Smith noted;

On coming to power the Bolsheviks had little sense of the form or tempo of the transition to socialism. The party was agreed on the need to nationalise the banks and a number of syndicates in the oil, coal, sugar, metallurgy and transport sectors, but beyond this there was little agreement about the extent of the socialist measures that could be undertaken.

Red Petrograd, p. 223 Cambridge 1985

They all agreed though from the start that socialism could not be built in Russia without an international working class revolution. This was not just because the working class in Russia was a relatively small part of the population or because it was not culturally capable of doing it (in Moscow and Petrograd literacy rates amongst workers were equal if not better than in some cities in places like Italy). It was simply impossible to overturn capitalist relations in a single country on its own in the face of a hostile capitalist world.

As it was the direction of the events was not decided simply by policy debates inside the Bolshevik Party, but by the reality on the ground. And the biggest part of that reality, both before and after October 1917, was the activity of the workers in the factories. More and more workers found that Tsarism had bequeathed a situation of increasing economic chaos. As Smith again tells us

…it was not until the summer of 1917 that the economic crisis fully manifested itself. The chief symptoms of the crisis were severe shortages of food, fuel and raw materials … By September the output of manufactured good throughout Russia had fallen by 40% since the beginning of the year. Shortages, spiralling costs, declining labour productivity and the heightened tempo of class conflict, made industrialists reluctant to try to maintain output. Increasingly they faced the stark choice of bankruptcy or closure

op. cit. p.145

The workers faced an even starker choice of unemployment and starvation so factory committees had been trying to keep their own plants going (who owned/ran the factories was not at first the issue). This rapidly worsening economic crisis did not end with the October Revolution. As the economic situation worsened the workers concluded that there was nothing for it but to take over themselves either when the boss fled or when it was clear that he intended not to organise the basic running of the establishment. As Soviet power had now been established they saw no alternative but to push on towards what they saw as socialism. Within three weeks of the October Revolution, Lenin recognised that workers’ control was a fact and thus the document that recognised this fact was not called a “Decree” (as was used to institute every other policy of soviet power) but “Instructions” or “Regulations” explaining how workers were to go about it in each factory and limiting the power of the employers to hinder them. [See Y. Akhapkin, First Decrees of Soviet Power, pp. 36-8, Lawrence and Wishart, 1970]

This was enthusiastically supported by the Left of the Bolshevik Party and Lenin was at their head at this point. He was encourager-in-chief of proletarian initiative, repeatedly stating that socialism could not be established “by a minority, by the Party”.

Its spirit rejects the mechanical bureaucratic approach; living creative socialism is the product of the masses themselves

Lenin, Collected Works Vol 26, p.288

However the situation was becoming dire. The Soviet Government could pass decrees of peace and land which tried to address those issues, but bread was an entirely different problem. Three years of war and the poor harvest of 1917 had its sequel in famine in the winter of 1917-18. According to Marcel Liebman “most parts of Russia were receiving only 12 or 13 percent of the amount of bread officially “provided for” by the food commissariat. In April this fell by half.” [Leninism under Lenin, p. 223].

The human misery this involved is difficult to exaggerate. In his Rethinking the Russian Revolution, Edward Acton compared its impact to that of the Black Death in the Middle Ages. There are multiple eyewitnesses to the unfolding tragedy from Jacques Sadoul, the French officer who came round to supporting the revolution, to Florence Flamborough, the pro-Tsarist British nurse, whose middle class Russian friends supplemented their two potatoes a day ration by selling their “family heirlooms”.

The consequences for the cohesion of the working class were just as dire. In Petrograd, the shortages of food and the lack of raw materials led to the closure of 266 of the 799 enterprises [Liebman loc.cit.]. 40% of the working class had abandoned the city by April. Of those who remained 60% were unemployed. Any party based in the working class had to share the same fate. Of the 43,000 who were in the Bolshevik Party in Petrograd in October 1917 only 13,472 remained there by June 1918. No surprise then that in March 1918 Bukharin spoke of the “disintegration of the proletariat” at the Seventh Party Congress.

This was the background to Lomov’s criticism of Gukovsky’s so-called Financial Reform Programme which E. H Carr [The Bolshevik Revolution Volume 2, p.147] tells us was actually just an admission that he could not draw up a state budget since he lacked the resources to do so. Lomov, Smirnov and the other Left Communists were arguing that there was no need to worry about balancing a budget if the money was spent on projects that helped develop socialism. They were following Marx’s injunction in 1850 that “if the democrats demand the regulation of the state debt, then the workers must demand national bankruptcy” [Address to the Central Committee of the Communist League]. Here the “democrats” were the right wing of their own party as represented by Gukovsky. They linked these arguments to their insistence that the economic collapse was nothing to do with the faith the revolution had put on workers’ initiative but on the fact that the revolution was not going far enough, fast enough. The workers in the factories were calling for nationalisation and the soviet power was dragging its feet on this. For the workers nationalisation would mean that the state would take over investment and supplies as well as guarantee the factory stayed open. For Lomov nationalisation, as long as it was accompanied by workers’ management of production would mean socialisation and lead to the dismantling of capitalist credit. This was in line with moving “coherently towards an organisation of market exchange without money”.

In the spring of 1918 Lomov was writing at a critical time. The Bolshevik Right could point to the massive economic problems and won over Lenin to the idea that one man management and the reintroduction of bourgeois specialists were necessary steps to restore industry. The Left would have to content themselves with the fact that the decree on nationalisation was finally brought in on June 28, 1918 and during the next few years the civil war meant that as government supplied most food rations and money was simply printed to finance the war it had virtually lost its value. However the policies that did arise (and later would be called “war communism”) were simply expedients forced on soviet power by circumstances. The question of the economic crisis would not go away, and famine and disease accounted for the vast majority of what the American economist Frank Lorimer has estimated were 14 million deaths in the period 1918-22. However, by then the RSFSR was already heading in the wrong direction...

The Financial Reform Programme of People's Commissar Gukovsky

- Economic Notes -

Truly, the blindest are those who do not wish to see(1)

Svoboda Rossii

With new tendencies come new songs…

Since the violent days of the proletarian assault on power, the irritated, exasperated bourgeoisie has sought everywhere to slander and spit on the great movement of the Russian working masses. Every new decree has enraged them. Every new victory has terrified them.

Now, reality has begun to offer them a few nice surprises. On the one hand, the Soviet power is inviting the old generals and officers to command the army, on the other hand, it begins to court the sharks of Russian capitalism. In these last few days, we have heard new “socialist” revelations from the People’s Commissar of Finance, Gukovsky, with which many representatives of the banking world feel at ease. But every conscious worker must wonder – are these leaders leading us down the right path?

The political economic and financial aspects are fundamental aspects of our revolution because its future greatly depends on the decisions which will be taken in these areas. In October-November the Soviet power adopted an absolutely consistent policy in this domain: the nationalisation of production, supported by the management of enterprises by the workers, also instantly including the banks. We knew that these economic and financial measures would completely destroy the bourgeois system of credit. During the period of destruction of all the economic basis of the bourgeois order, the bourgeoisie and the kulaks, who were driven out of the mills and factories which had fallen under the control of workers’ organisations, could not trust the financial measures of the socialist government and could not decide to trust it with their capital. In such a situation, the amount of money necessary for maintaining exchange must always grow, since credit in its old form collapses as long as direct exchange is no longer guaranteed. Following this, the financial policy of the working class is forced to reduce the issuing of banknotes as exchange is established, and as it is insured by a sufficient amount of money. The idea of restoring credit in its bourgeois form did not occur to those who made the Russian Revolution. In contrast, the Commissar of Finance of Soviet Russia found this idea necessary and in keeping with the programme. In the theses of his report read out at the Central Executive Committee (CEC) Comrade Gukovsky writes, “We must take urgent measures to restore the apparatus of credit in our country to clean up and reinforce the circulation of finances, in order to make paper money flow into the banks.” By logically developing his propositions, the Commissar of Finance reaches conclusions that are completely in keeping with the bourgeois order. (2) The budget of the Soviet republic is too large, it must be greatly reduced. Taxation must be unified and centralised. In his speech, Comrade Gukovsky declared that this year the budget is forecast to increase to 80-100 billion roubles compared to the 3.2 billion of the previous budget. This incredible increase in expenditure only makes him fear reading its accounts. Trying to comprehend the figures mentioned by Comrade Gukovsky, Sokolnikov (3) has already pointed out errors in his calculations. It turns out that the budget from 1917, including military expenditure, must have come to around 40 billion roubles, not 3 to 4 billion. The local Soviets must be denied the right to tax the population; the productivity of work must finally be increased, etc. This programme of financial policy has very little in common with that of the October Revolution. It is not by accident that Svoboda Rossii took on this new Commissar as their own. “Gukovsky proposes,” states the journal, “a fairly prosaic and ‘bourgeois’ programme of reforms which can be reduced, in short, to the restoration of what others destroyed, whether or not this is conscious, and or whether it is just not thought out, it sweeps everything off the road of socialism”. The other bourgeois groups have welcomed this programme. Thus Mr Bernatsky (4) regards Gukovsky’s report as “a challenge stamped with good sense against the reigning nightmare”, etc. Moreover, appetite grows with eating, and in its following issue, the bourgeois journal, Svoboda Rossii softly reproaches Gukovsky and his measures “part of which doubtless seem reasonable… However, in these same theses of Gukovsky, we see no overt and direct refusal of the old economic and financial policy of the Soviet power”.

The bourgeoisie is encouraged by sweet dreams of their lost paradise. The communist Commissar Gukovsky, in whom the bourgeoisie have discovered some “good sense”, and, most importantly, a “fairly bourgeois” programme, has unfortunately stopped in his tracks – there is no “overt and direct rebuttal” of the Bolshevist past, but everyone knows that it’s only that first step that will come at a cost.

But is the programme of the Commissar of Finance Gukovsky not perhaps characteristic of Soviet power? Let us listen to the Assistant Commissar, deputy Professor Bogolepov. (5) Summarising his analysis of Gukovsky’s theses, he declares, “the programme of Comrade Gukovsky, which we could modify a little – softening some parts, strengthening others – will make it possible for us to reach a better future.” All we need is an experienced apprentice at a university to touch it up just a little, and there you have the newly ready “programme”. It is fashionable to put all sorts of sticking plasters on one’s body; it “radically heals” rheumatism, gout and consumption! So what parts does the Assistant Commissar want to touch up?

Just like Commissar Gukovsky, Bogolepov is dissatisfied with the fact that “the Soviet power has quickly begun to raise taxes in the form of contributions. This form has a defect, it is poorly developed.” And then he says modestly, “We need a well designed fiscal apparatus.” Alas, it is true that the form of contributions is “poorly developed”, but the esteemed Assistant Commissar has forgotten one thing: during the revolution it is necessary to take the inappropriateness of the fiscal apparatus into account. The growth of the budget must be noted (whilst also accounting for the fall in the price of the rouble). What is the cause for this? Is it because there are too many functionaries paid by the Republic? Alas, it is very unlikely that this response would satisfy everyone. Professor Friedman (6) offers a far better explanation: “Socialism means the existence of a single regulated and planned economy. The budget of the state is integrated with the national economy.” As we have gone down the path of nationalising production, our budget naturally had to be increased. Comrade Gukovsky does not see this, he is terrified by these figures, he is their prisoner. The growth in our budget attests to that of the socialised economy. Comrade Gukovsky wants to reduce and make cuts to the budget, halting thus the process of organisation of socialised production and nationalisation of industry. The rest of us, whose programme opposed that of the Commissar of Finance, do not propose to retreat, but to move towards the rapid nationalisation of production, and so towards an inevitable growth in our budget. These expenditures are productive expenditures for our Soviet economy and for the construction of a socialist economy; in this time of profound disarray of the national economy, limiting the growth of the budget is a senseless and impossible task. We must choose: either we renounce the construction of socialism and reorder our finances through a series of bourgeois measures, or we construct socialism without fear of productive expenditure. Is the flaw of the revolution that it started to “zealously” tax these contributions? No, or it would deny itself any financial basis. The flaw of the revolution is that its financial commissariat is led by equally “zealous” commissars. How is the Commissariat intending to build a fiscal apparatus? “If the local authorities, which have no relation to the centre, get involved in business, it will inhibit working together… We must struggle decidedly against this.”

In other words, down with the power of local Soviets, long live the power of the Commissariat of Finance!

But where are we with the fiscal apparatus? I hear you ask. Alas, nobody is telling us anything. They merely respond that even the existing fiscal apparatus must be destroyed, despite it being born in the revolution and having worked more or less fine: that is, the local Soviets. Certainly their work did not please the bourgeoisie too well, but according to the revolutionary experience of several Soviets (in Siberia, Simbirsk, Moscow, Ivanovo-Voznesensk), they are not just limited to contributions, they have taxed gross revenues, in particular those of the village kulaks, which is the most important thing (in Siberia, in Simbirsk etc). Now (given that times have obviously changed), it has been resolved that we should “struggle decisively against” them. With such a decision, the leaders of our Commissariat of Finance condemn them to degeneration into a mere bureaucracy, incapable of realising their functions as Soviets.

But we have to save the day! It is no coincidence that Comrade Gukovsky has shown the supposed expenditures to a shocked Russia. It is true that credulous speakers and readers have not asked to examine the figures in detail, otherwise they would have discovered some interesting facts. For example, you, reader, think in your innocence that all of our foreign debts were cancelled long ago (even if comrade Gukovsky considered their non-payment an error, to the great pleasure of the bourgeoisie). You are wrong. Our financiers are politicians, realists and enemies of the “revolutionary phrase”, they “intervene” and, probably by intervening in the future, Comrade Bogolepov has the intention of allocating one billion four hundred thousand roubles of the budget to paying interest on foreign loans. And it is undoubtedly on these figures that Comrade Gukovsky is basing his report!

Why do the comrade commissars not say a word about this in their speeches? And where do these figures come from? No doubt “from themselves”. This is why we are persuaded that the comrades have committed an unforgivable error by not analysing all of the figures. It is entirely likely that there are many interesting and instructive things to be found there, and in particular for the partisans of the “revolutionary phrase”.

Saying that, we do not wish to deny the terrible danger of a financial crash. Indeed, if we impotently hesitate, looking back with nostalgia to the peaceful past, or by “softening some parts” and “strengthening others”, the crash will be inevitable. Instead of “strengthening” it, the revolution must sweep away without ambiguity all forms of discourse and political lines that are in reality nothing but the lamentable slurs of terrified philistines. The revolution in Russia can only win by being socialist. We do not need to reform old practices, we need to subject everything to the necessities of the new socialist policy. In his speech dedicated to critiquing the programme of bourgeois reforms in their essence (which even the bourgeoisie highlights) of Comrade Gukovsky, Comrade Bukharin has shone light on a path that was not discovered by cabinet scholars but by the October Revolution itself. Without straying down the path of the bourgeoisie, without opportunistic detours, we must move coherently towards an organisation of market exchange without money. Such is the course of the development of the revolution. Currently they are trying to turn it from this path to orient it towards the restoration of bourgeois credit and towards other similar reforms. The left communist Comrade Bukharin has characterised these attempts of our commissars very well. “It is senseless to expect,” he says, “to restore the bourgeois form of credit during the socialist revolution.”

Circumstances are now forcing the Russian Revolution, fumbling and reflecting, to search for its way forward. We must summon all our strength to prevent the diversion of the revolution on to the path of bourgeois realist plans and reforms. Commissar Gukovsky proposes a heavily realist, heavily bourgeois, programme of reforms which leads, in the words of Svoboda Rossii, to “the restoration” of what the October Revolution destroyed. Comrade Gukovsky demands that the organ leading the Soviet Republic clearly express itself on this programme, and furthermore, instead of responding, that the CEC addresses it to a commission. So has it approved it? No, in the CEC we can see in certain places a strong critique of Gukovsky’s programme. So has it perhaps rejected it? Alas, no. So Soviet Russia remains with no financial programme, whether socialist or bourgeois. By contrast, it does have a recognised head, Commissar Gukovsky, and a deputy-head, Comrade Bogolepov, who together are passing the essentials of the bourgeois programme, as well as a commission before which this programme is quietly dismissed. Nothing has changed. No-one has approved nor disapproved it. Everything has gone well, thank God! We can sigh with relief. We are persuaded that the CEC was wrong to refer Gukovsky’s programme to a commission. It deserves to be consigned to the dustbin of history, to be subject to the rigorous criticism of mice along with the theses of the leaders of our financial policy. The working class must be brave enough to show the revolution the path which will not lead it into the bourgeois swamp but will open the way to the socialist future.

A. Lomov

(1) Svoboda Rossii (The Liberty of Russia) was the journal of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets). Suppressed in July 1918.

(2) Lenin’s comment on Gukovsky’s plan only underlines the enormous dilemmas which were raised by the revolution as it waited for the international proletariat to make its own class response: “I shall not dwell upon whether this plan is good or bad. One thing only is clear to me: at the present time it is impossible to fulfil even the best plan in the financial sphere because as a matter of fact the machinery has not been organised for fulfilling it.” Speech On The Financial Question At The Session Of The All-Russia C.E.C. 18th April 1918. marxists.org

(3) Grigori Yakovlevich Sokolnikov (1888-1939): Bolshevik since 1905, imprisoned in Moscow in the autumn of 1907, exiled to Siberia and then to Paris in 1909, returned to Russia after the February Revolution of 1917 on the same train as Lenin. He was elected to the Central Committee (of which he would remain a member until the mid 1920s) and to the editorial staff of the Central Organ of the Party at its 6th Congress. Member of the Political Bureau at the time of the October Revolution, he was then part of Zinoviev’s group and then rejoined the United Opposition before leaving it following its declaration on the 16th October 1926 that it would renounce the fractional struggle. He was prosecuted at the second Moscow Trial (January 1937) where he was sentenced to ten years in prison. He died in obscure conditions in 1939.

(4) Mikhail Vladimirovich Bernatsky (1876-1943): Russian economist, Minister of Finance in Kerensky’s Provisional Government from 25th September 1917. Arrested in October, he was imprisoned for a time in the Peter and Paul Fortress before being released, to then join the forces of the Whites. He effectively became Minister of Finance in the governments of Denikin, and then of Wrangel.

(5) Dmitry Petrovich Bogolepov (1885-1941): Social Democrat since 1907, academic specialising in financial law, he became Deputy Commissar of Finance, Director of the State Treasury Department and participated in the drafting of the first Soviet Constitution. Rector at the University of Moscow from 1920 to 1921, he then worked as a professor and collaborated in Gosplan.

(6) Mikhail Isidorovich Friedman (1875-1921): Russian economist, Assistant Minister of Finance in the Provisional Government from 27th July 1917, he later lectured and produced a few scientific studies on the Bolshevik government accounts.

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.