You are here

Home ›The Tours Congress and the Birth of the French Communist Party

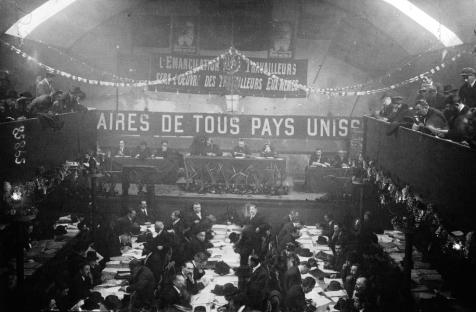

It is now 100 years since the Tours Congress of 25 to 31 December 1920, when the majority of delegates of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) voted to join the Third International.

Whilst the Communist Party of Italy (PCd’I) was formed on the basis of a real, open split from the pacifist, opportunist and parliamentarian Social Democrats, the French Communist Party (PCF) adhered to the positions of the International but held onto the gangrenous parliamentarist and opportunist majority that led it.

It was an evolution in a completely opposite direction. The left fraction(1) would have to wait several years before it came to lead the PCF (from 1923 to 1924) before being rapidly expelled from it by the bolshevisation, and then the stalinisation, of the party. The PCd’I, on the other hand, was led by its left wing from its creation, having broken quite cleanly with the opportunists of all shades, before being marginalised by the leadership in 1924, then being officially expelled from the party in 1926 at its third congress in Lyon.

Within the SFIO, a compromise was reached between a very weak left (since its two principal spokesmen, Loriot and Souvarine, were in prison at the time of the Congress) and a strong majority current from the old Socialist Party. This current had remained, at best, “centrist”, not to say “opportunist”. Thus from its beginning, the Communist Party was led by a centre infested with opportunists, more or less “remorseful” for having betrayed the sacred union during the imperialist war.(2) Its most typical representatives were Frossard, a born conciliator and a skilled manœuvrer, and Cachin, ex-emissary of the French government of national defence and given the job of bringing Italy into the First World War.(3)

The PCF could have been a true communist party from its creation like the PCd’I if the Committee of the Third International (CTI), which had raised the banner of the proletarian International during the war, had been able to lead it.

In order to understand the challenges in creating the PCF, we must return to the first imperialist world war.

1. A promising start: the Committee for the Third International (CTI)

For Souvarine, chief animator of the left tendency in the SFIO, the creation of the Comintern in March 1919 paved the way for a break with the war-happy Social Democrats. It was therefore definitively part of the movement of Zimmerwald and Kienthal. From his point of view, it was necessary to join the Comintern and adhere to its political principles. The international conferences accelerated the movement in France against the old opportunist Social Democracy, which had betrayed the principle of proletarian internationalism. On 17 April 1919, the Committee for Reviving International Relations (CRRI, a regroupment committee for socialists, syndicalists and anarchists who opposed the war) approved the creation of the Comintern and decided to join it. Thus on 8 May 1919, the CRRI decided to transform itself into the CTI.

Absent from the leadership of the CRRI, which at this time (late 1918 to early 1919) included non-members of the SFIO, Souvarine however maintained close relations with its most prominent members: Monatte, Loriot, Rosmer, etc. At this time, Souvarine was still a member of the SFIO and because of this, he sought to be able to write as many articles as possible in the organs of the Socialist Party to win over as many comrades as possible to communism. And it was he who was in charge from 1919. It is also through him that we may understand what happened next.

So for the first half of 1919, Souvarine did not directly oppose the Socialist Party, but argued for the necessity of supporting Russia and its revolution in the various press organs of the SFIO wherever he could.

He eventually decided to write his open letter to Citizen Frossard in Le journal du peuple (“The People’s Paper”) on 18 October 1919, denouncing the fact that “the Socialist Party remains silent”, and asking whether “the leadership of the Socialist Party will persist in its mutism?” Then, in Autumn 1919, in order to better defend the Third International, he gave up on staying with the “centrist”(4) fraction of Jean Longuet, Raoul Verfeuil and Paul Faure, which would found a Committee for the Reconstruction of the International (CRI, i.e. the Third International). Souvarine would derisively dub them the “reconstructeurs”. When the Socialist Party lost the national election in November to the infamous “Blue Horizon Chamber”, a radicalisation towards the left could be seen in its ranks. On 11 November, he wrote to Jules Humbert-Droz, “Our ideas are making a tremendous leap.” He joined the CTI at last.

Meanwhile, the CTI was accumulating positive results within the SFIO. At the Strasbourg Congress in February 1920, the CTI gained 4621 mandates with a tendency of militants moving more and more to the left. It was then that the CTI realised that it had no press organ worthy of the name for its propaganda. Souvarine’s role was paramount once again in creating Bulletin communiste as the organ of the CTI.(5)

The first issue of Bulletin communiste stated in its editorial,

We will be able to conclude that our thesis shall triumph easily once it becomes possible to distribute it better and more numerously than we have done so far. In other words, the task of the Committee of the Third International is to create the organ which will express its views, formulate its doctrines and above all define its conceptions ... The unanimous Committee has understood this perfectly well, and has decided to publish this Bulletin communiste, while we await the moment when we can create a newspaper which easily reaches and penetrates the working masses.

Issue 1, The Third International in France

The Bulletin would become what Lenin would call a collective organiser (meaning a revolutionary paper). The Bulletin would be the organiser that opened the path to the future Communist Party.

The Bulletin communiste would become the organ of the Communist Party (SFIC) from Issue 50, on 10 November 1921. Souvarine was its main editor as well as its head of publication. Against all odds, Bulletin communiste would survive as a journal of the opposition and of Souvarine until 1933, when he had already been expelled from the PCF for 7 years.

2. A stillborn Communist Party: a split too far to the right

At the Tours Congress of the SFIO in December 1920, the split for those who wanted to create a real Communist Party took place. However, the main members of the CTI were absent from the Congress because they were in prison. As it became a stronger force, the CTI drew the wrath of the State upon itself. In April and May, there were many arrests of members calling for revolutionary communism – that is, militants of the CTI and those of groups “some of whom called themselves a ‘Communist Party’, others a ‘Federation of Soviets’”, as Souvarine wrote. The main militants of the CTI – Monatte, Loriot, Monmousseau and Souvarine – were imprisoned on charges of “plotting against state security”, and in the case of Loriot, for “incitement to murder, pillage and arson” thanks to nefarious laws from 1893-4. Because of this, real discussions to define the political orientations of this new party did not take place.

This left the field open for the “reconstructeurs” to block every effort to fully support the Soviet Revolution and join the Comintern, and, on a more basic level, to do everything they could to prevent total solidarity from being expressed with the accused.(6) So we find in the Bulletin communiste a whole series of articles denouncing the opportunist, parliamentarian politics of the “reconstructeurs”, full of false pretences and empty words. Souvarine tersely summarises the situation in the Socialist Party thus: “We have had enough of revolutionism in words and reformism in deeds.”(7)

The only progress made consisted in the creation of a new party attached to the Comintern.

The leadership remained in the hands of the “centre”, with Frossard, who kept himself in the position of general secretary, and Cachin, who ran l’Humanité. Cachin and Frossard supported the decision to join the Comintern, but just to swim with the current rather than due to any conviction. After the split, they led a passive resistance to the transformation of the Party. The leadership did not openly oppose the decisions of the Comintern. They nominally accepted but did not apply them, they dragged their feet, bided their time, and systematically covered for everyone who publicly attacked the resolutions of the Comintern.

Souvarine recognised the difference in political clarity between the PCF and the PCd’I when he reported on the creation of the latter, writing as well in issue 4 of Bulletin communiste on 7 January 1921,

Above all, the split has brought about the welcome result of the formation of an intransigent class party, capable of orienting the revolutionary movement towards the conquest of political power and the dictatorship of the proletariat ... The old party has retained two thirds of the pre-Livorno membership. But it also retains its weakness: a cowardly staff from whom the masses increasingly turn away in favour of revolutionary solutions.

For more in-depth information on the evolution of the PCF and its left currents which were all excluded, all published issues of Bulletin communiste are available here: archivesautonomies.org, as well as the book Envers et contre tout (“Towards and Against Everything”), which recounts the evolution of all opposition groups in France from 1927 to 1939.

We have already published 100 Years Since Livorno, an article by Onorato Damen from 1971 on the creation of the PCd’I which has the immense advantage of having been written by a participant at the Congress.

MO

The above article was drafted in French in December 2020 as an introduction to the 100 Years Since Livorno document already published (and referred to at the end). The CWO translated it in January 2021 but thought it worth publishing as a separate article in English in its own right as it is an episode that is little known in the English-speaking world.

(1) Chiefly represented by Souvarine, Rosmer, Monatte and Treint.

(2) The leadership of the Socialist Party supported the various governments of national unity, its parliamentarians voted in favour of war credits and finally, after the first months of the war, the various governments contained Socialist ministers.

(3) Sent to Italy to give money to Mussolini (still a member of the PSI at the time) so that he would publish a chauvinist newspaper calling for Italy to enter the war on the side of France. This was the same Cachin who boasted of having cried tears of joy when he saw the French flag flying again in Strasbourg in 1918.

(4) The SFIO was therefore made up of a conciliatory “right”, a “centre” which tried to reconcile the two tendencies confronting each other, and a “left” which opposed the war and wished to join the communist movement and the Comintern.

(5) It is important to stress that Souvarine was able to play such a role in the creation of the Communist Party because he was completely in line with the majority of the revolutionaries of the time. So it is not a question of sanctifying an individual. We must recall that after the second imperialist war, he was “supported” by the CIA. But that’s another story.

(6) Cf. article “Loyauté des Reconstructeurs” (Loyalty of Reconstructeurs), Bulletin communiste, issue 17.

(7) Cf. article “Le Conseil national socialiste” (The National Socialist Council), Bulletin communiste, issue 16.

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.