You are here

Home ›Radek's Theses on Imperialism (1915)

The wars that capitalism is now unleashing, and the ones yet to come, are a product of the imperialist epoch. Our understanding of what imperialism means is based on more than a century of experience and reflection. Much of that we owe to revolutionaries who came before us, and in that spirit we have translated the piece below, drafted in the midst of the First World War.

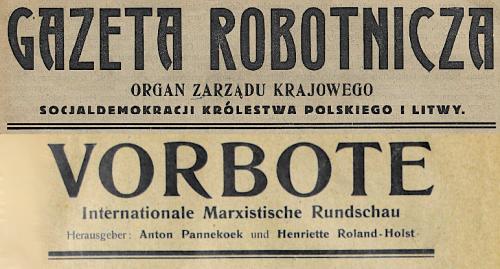

These theses were originally written around September 1915 and published in Gazeta Robotnicza (Workers’ Gazette), the paper of the ‘rozłamowcy’ faction(1) of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL). They were signed by Karl Radek, Mieczysław Broński-Warszawski and Władysław Stein-Krajewski. In April 1916 they were reproduced in Vorbote (Herald), the German-language paper of the Zimmerwald Left under the editorship of Anton Pannekoek and Henriette Roland Holst. Having read them, Lenin responded with a lengthy critique arguing in favour of national self-determination published in October 1916.(2) The upshot of their differences was that Vorbote did not appear again. The theses of Gazeta Robotnicza have been previously translated into English in 1976, but to our knowledge they are not available anywhere online. As such, we have decided to make our own translation, based on both the Polish original and the German reproduction.

This document should not be confused with the theses on the right of nations to self-determination drafted by Nikolai Bukharin in November 1915, and co-signed by Georgy Pyatakov and Yevgenia Bosch.(3) However, they are not unrelated. Lenin, in his frustration with Pyatakov and Bosch for signing Bukharin’s theses, blamed it all on the influence of Radek:

They didn’t think it out. They didn’t read. They didn’t study. They listened two or three times to Radek (he has the old “Polish” disease: he is confused on this)—and signed.

Lenin to A.G. Shlyapnikov, March 1916

The old “Polish” disease was, of course, opposition to national self-determination. This was a position first developed by Ludwik Waryński and his “Proletariat” Party in the 1880s, and afterwards taken up by Rosa Luxemburg and the SDKPiL.(4) Radek, Broński and Krajewski were all part of that young generation which came to socialist politics around the turn of the century. They joined the SDKPiL and participated in the revolution of 1905. Facing repression, they moved about Europe, extending their political connections. While Broński and Krajewski began to work closely with Lenin and the Bolsheviks, in Germany Radek joined Pannekoek and the Bremen Left. Already in 1912, Radek argued that:

the intellectual life of the [German] Party … did not keep pace with the tempo of capitalist development … Because socialism is not a ‘current’ issue for wide circles of the Party, it is not deemed a concrete answer to the imperialist questions. Socialism is not set as a rallying cry against the imperialist war-cry, but, rather, answers are sought in terms of Realpolitik.

Radek, Our Struggle Against Imperialism, May 1912

For Radek, and those around him, “the era of mass-struggles has already begun … the possibility of imperialist conflicts, as well as of economic and political conflicts between the forces of reaction and the working class, can set the ball rolling at any moment”. Two years later, the outbreak of the First World War set that ball rolling. Radek, Broński and Krajewski found themselves in the safe-haven of Switzerland, where they could continue to publish Gazeta Robotnicza. As internationalists both in theory and practice, it was only natural they joined the Zimmerwald Left. Come the February Revolution, they all sided with the Bolsheviks. While Krajewski was back in Warsaw by June 1916, Radek and Broński were with Lenin on that infamous train journey from Zürich to Petrograd.(5) In the following years, Radek, Broński and Krajewski contributed to the process of formation of communist parties in Poland and Germany, and worked for the Communist International and the Russian Party. By that point however, they abandoned their previous position on the national question (Radek in particularly appalling style, briefly becoming an advocate of “National Bolshevism” in 1923). Ultimately, having to various degrees participated in the anti-Stalinist oppositions, they all perished in the purges.

But before and during the First World War, they defended their position on the national question, even against Lenin (with whom they were otherwise in agreement). The 1915 theses are the most complete exposition of their views at the time – views which, to a large degree, still describe the reality we find ourselves in today. The authors understand that capitalism had entered the imperialist epoch, which signifies the task of the proletariat is no longer “the extension or the expansion of capitalism, but its overthrow.” In this new historical period, “appeals to Marx’s position on the national questions” are no longer relevant. The solution to national oppression lies not in “establishing new and re-establishing old national states” but in the united struggle of the international working class against the system as a whole. They see all talk of “right of nations to self-determination” as inheritance from the corrupt Second International, a “right” that not only cannot be realised in the imperialist epoch, but is also inapplicable to socialist society (where the nation will no longer take the “character of a political-economic unit”). They warn how in practice the slogan “replaces the social-revolutionary perspective” and leads to division within the working class movement. The consequence of this we can see today, as the idea of the nation has dethroned the idea of class among much of the working class (it is only the small revolutionary minority that still clings to the latter).

Where the theses leave some room for ambiguity, and maybe show residues of Second International language, is in relation to “democratic rights”, or the “the struggle for the democratisation of political conditions within the framework of capitalism”. Clearly, as the authors indicate, “the struggle for immediate demands” needs to be linked with the “revolutionary perspective”, but we have to be clear this cannot mean the separation of the communist programme into “minimum” and “maximum” parts, as we have argued elsewhere.(6) In fact, the Russian Revolution posed the question in a different manner to how the authors of the theses expected – the “abolition of Tsarism” came about as a result of the revolutionary struggle of the working class which did not stop there, and a post-war revolutionary wave was initially sparked in the “undeveloped” East rather than the “ripe” West (where the proletariat, still under the reformist influence of what remained of the Second International and facing a more powerful capitalist class, was unable to take power).

Nevertheless, the theses stand as a little known piece of the internationalist tradition, and the latter parts shed light on how these revolutionary militants from an “oppressed nation” came to the conclusion that national self-determination was no solution.

Dyjbas and TinkotkaCommunist Workers’ Organisation

October 2023

Notes to the Introduction:

(1) In 1911 there was a split in the SDKPiL between the ‘zarządowcy’, who backed the party centre in Berlin led by Luxemburg and Jogiches, and the ‘rozłamowcy’, who had personal, tactical and organisational disagreements with the centre and were closer to the Bolsheviks. This divide would later contribute to the so-called ‘Radek affair’ – a peculiar incident in which Radek was accused of stealing resources from the party and in 1912 expelled by the party centre (Lenin and Pannekoek, among others, stood in his defence). What united both factions however was their stance on war, revolution and the national question, which eventually helped the SDKPiL to reunite in November 1916.

(2) Lenin, The Discussion On Self-Determination Summed Up, marxists.org

(3) Available here though, despite what the introduction says, Bukharin’s theses were never published in the pages of the 1915 Kommunist. libcom.org

(4) On Waryński and Luxemburg, see: leftcom.org

(5) Though Radek was denied entry to Russia and had to get off in Stockholm.

(6) See The Democratic Revolution – A Programme for the Past?, available as a PDF here: files.libcom.org

Theses of Gazeta Robotnicza on Imperialism and National Oppression

Adopted by the editorial board of Gazeta Robotnicza, 9-10 September 1915, published in Gazeta Robotnicza, issue 25, January 1916. Reprinted in Vorbote, issue 2, April 1916.

I. National Oppression and International Social Democracy

1. Imperialism represents the tendency of finance capital to transcend the boundaries of the nation state, in order to conquer overseas raw material and food sources, spheres of investment and markets and to create larger state apparatuses by merging together, even in Europe, neighbouring, economically complementary areas without taking the nationality of their inhabitants into account. This latter tendency is also supported for military reasons, since imperialism generates the need for attack and defence by aggravating the contradictions between states.

The tendencies of the colonial and continental annexations of imperialism signify the increase and generalisation of national oppression, which hitherto only existed in multi-national states where, for historical and geographic reasons, one nation ruled over others.

2. This national oppression contradicts the interests of the working class. That same imperialist bureaucracy, which is the organ of national oppression, also becomes the bearer of the class oppression of the proletariat of its own nation, it applies all the means used in the struggle against the oppressed nation against the struggling proletariat of the ruling nation. As far as the working class of the oppressed nation is concerned, national oppression thus limits their class struggle not only by diminishing their organisational freedom and lowering their social level, but also by stirring up feelings of solidarity with their own national bourgeoisie. With its hands and feet bound, politically corrupted by nationalism, the proletariat of the oppressed nation becomes a helpless object of exploitation and thus a dangerous competitor (by keeping wages down and breaking strikes) of the workers of the oppressing nation.

The victorious state, by forcing foreign territories into its own framework, creates new arenas of war. The defeated state will strive to claim its territories back, because they are of economic and military importance, or because slogans of national revenge provide the best cover for the imperialist policy of the defeated state.

3. A Social Democratic Party must therefore oppose with the utmost energy the annexation policy of imperialism as well as the policy of national oppression that is its consequence. To the imperialist claim that the acquisition of the colonies is necessary for the development of capitalism, a Social Democratic Party replies that in Central and Western Europe, as in the United States of America, the time has already come to transform capitalism into socialism, and socialism needs no colonies, because socialist nations will be able to provide undeveloped nations with disinterested social aid, so that, without having to rule over them, through exchange they will be able to receive back anything they are geographically incapable of producing themselves.

The historical, and now fully realisable task of the proletariat is not the extension or the expansion of capitalism, but its overthrow. To the claim that annexations are necessary in Europe for the military security of the victorious imperialist state, and thus the security of peace, Social Democracy replies that annexations only aggravate contradictions and in so doing increase the danger of war. But even if this were not the case, Social Democracy cannot have a hand in creating any peace that is based on the oppression of nations. Because if it were to endorse such a peace, it would open up a chasm between the proletariat of the ruling and the oppressed nations. The proletariat of the ruling nation, by endorsing annexations, would be responsible for imperialist policy, and by its continued support for that policy, would become a stooge of imperialism; on the other hand, the proletariat of the oppressed nation would unite with its own bourgeoisie, it would see the proletariat of the ruling nation as its enemy. Instead of the international struggle of the proletariat against the international bourgeoisie, we would have the division of the proletariat, its spiritual corruption. It would stand completely paralysed in its struggle against imperialism, both for its everyday interests and for socialism.

4. The starting point of the struggle of Social Democracy against annexations, against the violent capture of oppressed nations into the borders of the annexing state, is the rejection of all defence of the fatherland, which in the epoch of imperialism is the right of one’s own bourgeoisie to oppress and plunder foreign nations. The struggle of Social Democracy consists in denouncing national oppression as an attack on the interests of the proletariat of the ruling nation, in demanding all democratic rights for the oppressed nation, including freedom of agitation for political separation, since democratic principles demand that agitation, in whatever form, be combatted through ideas rather than force. By thus rejecting all responsibility for the consequences of imperialist policy of oppression, and combating it without compromise, Social Democracy in no way stands for the establishment of new border posts in Europe, or the re-establishment of those that have been torn down by imperialism. In those areas where capitalism has developed without its own state, historical development has shown that an independent state was by no means an absolute prerequisite for the development of the productive forces and the implementation of socialism. Where the wheel of imperialism steamrolls the already-formed capitalist state, in the brutal form of imperialist oppression the political and economic concentration of the capitalist world is accomplished, which paves the way for socialism. Social Democracy, based on the consequences of this concentration, which stirs up the masses through national and economic oppression, must educate the working masses of both the oppressed and the oppressing nation towards the united struggle which alone can overthrow national oppression along with economic exploitation by leading humanity through imperialism towards socialism.

If Social Democracy in the developed capitalist countries can conceive of the overthrow of imperialism not in the return to old forms, in establishing new and re-establishing old national states, but in the appeal “Down with borders!”, then to clear the way for socialism, for which the economic relations here are already ripe, this task also gives rise to the demand “Down with the colonies!”, which crowns our struggle against the national oppression of imperialism. The colonies are sources of new streams of profit for capital, which hopes to prolong its life. Indeed, capitalism even seeks to draw physical power from them by creating native armies, which it will use against the revolutionary proletariat just as readily as it currently uses them in the world war against its competitors. This international rejection of colonial expansion, which can only be achieved by the proletariat in revolutionary struggle, will by no means signify a regression of the developed capitalist countries into barbarism, as the social-imperialists claim. For years in the most important countries of the East (Turkey, China, India) there has been a notable growth in bourgeois elements which are capable of carrying out independently the tasks of developing the productive forces still ahead of capitalism there. By demanding the renunciation of the colonial expansion of European capitalism, and by utilising the struggles of the young colonial bourgeoisie directed against European imperialism to intensify the revolutionary crisis in Europe, Social Democracy serves to accelerate the moment when the hour of socialism strikes also outside Europe, it will support the proletarian struggles in the colonial countries against European and domestic capital, and will also try to spread the perspective among the colonial proletariat that its permanent interest requires solidarity not with its national bourgeoisie, but with the European proletariat fighting for socialism.

5. Just as it is not possible on the terrain of capitalism to reshape imperialism in the interests of workers, to bring militarisation to an end, nor can it be stripped of its tendency towards national oppression, nor made to recognise the right of self-determination of peoples. This is why the struggle against national oppression must be conducted as a struggle against imperialism, for socialism.

In order to lead to the liberation of the nationally oppressed masses, the struggle of Social Democracy must be a social-revolutionary struggle that strives to destroy the domination of capitalism. Because only by abolishing capitalist private property can the working class also abolish the motive for national oppression, which is but a part of class domination. Socialist society will know no oppression, but will confer on all nations the right to collectively decide on all their needs, and give every citizen the freedom to determine their tasks with others.

The direction of the struggle against national oppression in the wide stream of revolutionary mass struggle for socialism means that this struggle is not to be postponed to some uncertain time, nor are the oppressed peoples to be reassured about a better future, since the revolutionising consequences of the imperialist epoch simultaneously prepare it for the period of socialist revolution, in which the proletariat shatters all its chains.

II. The So-Called Right of Nations to Self-Determination

The formulation of the right to self-determination is inherited from the Second International. In the Second International, the formulation played an ambiguous role: on the one hand, it was supposed to express a protest against all national subjugation; on the other, it was to express the readiness of Social Democracy to “defend the fatherland”. On questions pertaining to individual nations, it was utilised only to avoid examining their concrete content, and their tendencies of development. While the consequences of the policy of defence of the fatherland in the world war demonstrate the counter-revolutionary character of this formulation in the era of imperialism with full clarity, its misleading character as a formulation aimed at articulating our struggle against national oppression remains, to many, obscure. Since it sharply expresses opposition to imperialist tendencies of oppression, some revolutionary Social Democrats (e.g. in Russia) see it as a necessary tool for our revolutionary agitation. Although we fully appreciate the proletarian revolutionary aim that they pursue with propaganda containing the slogan of the right to self-determination, we do not recognise this formulation as a correct expression of our struggle against imperialism. The reasons for this are as follows:

1. The Right to Self-Determination Cannot be Realised Within Capitalist Society

Modern nations represent the political-cultural form of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie over the masses who speak the same language. Divided into classes, the nation has no common interest and no common will. “National” policy is that which corresponds to the interests of the ruling classes. This in no way contradicts the existence of political democracy in individual capitalist countries. The influence of the economic domination of capital over the masses, its systematic and continuous processing by all organs of the capitalist state (church, school, press), allows the bourgeoisie to impose the will of capitalism onto the majority of the people in a roundabout way, and to make the will of capitalism appear as that of the people. Herein consists modern democracy! In the relationships between nations, the interests of the stronger bourgeoisie or of a union of several of its national groups rules the day. Since capital cannot hold off on its expansion until it has obtained economic and cultural influence in those areas where it wants to expand, which would take decades, and since such peaceful expansion is often opposed by the conflicting will of other capitalist groups and thus made impossible, the forms of political democracy are eliminated in the questions of annexation of foreign territories, and open violence rules. Here, the referendum can only be used as open deception to sanction acts of violence. It is therefore utterly impossible on capitalist terrain to make the will of nations a deciding factor in questions of border alterations, as the so-called right to self-determination demands.

Insofar as this demand is interpreted as such, as though an individual part of a nation decides for itself whether it belongs to this or that state, it is not only utopian – because capital will never leave the determination of its state boundaries to the people – but it is also exceptionalist, and undemocratic. If the popular masses of a given country had the decision over its borders in their hands, it would have to be made at the level of the entire state, not a particular province. Indeed, where it is a dispute between two countries, democracy requires an agreement between their democratically elected representatives be reached. If, for example, the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine [then Elsass-Lothringen] by France gave rise to a national question there – as the section of the population there which longs to return to the German Empire hopes – if it led to the danger of revenge from Germany, i.e. if the latter threatened France with a new war, it is clear that it would be in no way democratic to burden the French people with all of these consequences without having had a say in the decision, simply on the basis of the will of the Alsatians.

2. The Right to Self-Determination is Inapplicable to Socialist Society

The so-called right to self-determination is also used with the note that it will only be realised under socialism and thus expresses our aspiration for socialism. To this we raise the following objection. We know that socialism will abolish every national oppression, because it will abolish the class interests that lead to it. Nor do we have any reason to assume that the nation in socialist society will take on the character of a political-economic unit. In all likelihood, it will only have the character of a cultural and linguistic unit, since the territorial division of the socialist cultural area, insofar as such a division will exist, can only be made according to the needs of production, whereby it will naturally not be up to individual nations to decide this division on the basis of their own authority (as the “right to self-determination” demands), but to all interested citizens to have a say. The adoption of the formula of “the right to self-determination” for socialism is a complete misunderstanding of the character of socialist community.

3. The Tactical Consequences of the Use of the Formula of the Right to Self-Determination

Like every utopian slogan, it spreads false conceptions about the character of both capitalist and socialist societies, and misleads the proletariat in its struggle against national oppression. Instead of openly telling the proletariat that they cannot free themselves from the danger of the arbitrary determination of their fate by the military and economic needs of a capitalism torn apart by contradictions, any more than they can from the dangers of wars, without having abolished capitalism, the slogan arouses unrealisable hopes in capitalism’s capacity to adapt to the national interests of weaker nations. In this way, the slogan, even against the will of those who preach it, replaces the social-revolutionary perspective, that most important consequence of the world war, with a national-reformist one. In the programme of the proletariat of oppressed nations, the slogan of the right to self-determination could serve as a bridge to social-patriotism. As the experience of the Polish, Ukrainian and Alsatian workers' movements shows, this slogan serves as an argument for the nationalist current within the working class, for hope in the warmongering parties, by which the international front of the proletariat is broken.

In the programme of the proletariat of oppressed nations, presented as a solution to the national question, the slogan gives the social-imperialists the opportunity to present our struggle against national oppression as historically unjustified sentimentality, and thus to undermine the trust of the proletariat in the scientific foundation of the Social Democratic programme. Indeed, it could sow the illusion among the proletariat of the oppressing nation that they, contrary to the proletariat of oppressed nations, already have self-determination over their fate, and are therefore duty bound to defend their “common” interest, their will, alongside other sections of the nation. If however the slogan of the right to self-determination is used agitationally as one that could be realised only by the social revolution, i.e. one that leads us into the struggle for socialism, then – quite apart from the impossibility of autonomy for a particular national group of citizens of socialist society over the general common interests – it is inadequate. Because in the transitional period, when socialism is economically already possible but the social-revolutionary class struggle has not yet begun, our tactical interests require sharp emphasis on the clear, undiluted slogan of socialism, of social revolution, as the central idea that expands and strengthens every part of our struggle.

4. Assessment of the Question from a Historical Perspective

Any appeals to Marx’s position on the national questions in the period of 1848-1871 have no value whatsoever, because if Marx supported the liberation of Ireland and the independence of Poland, he simultaneously opposed the independence movements of the Czechs, the Southern Slavs and others. On the contrary, Marx’s position shows that it is not the task of Marxism to formulate stances on concrete questions through abstract “rights”. The negative position of Social Democracy towards every national oppression, as we have shown in our theses, is the result of the incompatibility of the class interests of the proletariat with any support for the ruling classes. The positive position towards every concrete national problem (of Alsace-Lorraine, of Poland, of the Balkan question) can only succeed on the basis of the concrete developmental tendencies of this question itself within the framework of the whole imperialist epoch.

The characterisation of the proper Marxist position against the formulation of the right to self-determination as Proudhonist is absurd. Proudhonism negated the national question and wanted to solve all social questions not through class struggle, but through petty bourgeois association. The Marxist opponents to the so-called right to self-determination do not deny the national question, and refuse to postpone the struggle against national oppression until after the victory of socialism. While they cannot in any way be accused of Proudhonism, the method of the supporters of the right to self-determination can be characterised as that of a schematic application of democratic concepts.

5. Polish Social Democracy and the Question of the so-called Right to Self-Determination

The SDKPiL took its position on the Polish question on the basis of its analysis of the tendencies of Poland’s economic development in 1893. The twenty years that followed in the history of Poland have entirely confirmed this analysis, most recently in that during neither the 1905/06 revolution nor the world war did any serious social class express any desire for independence in Poland. The SDKPiL rejected the slogan of the right to self-determination when it was raised in the International Congress in London in 1896, to avoid taking a stance in relation to the concrete slogan of the Polish social-patriots, who had inscribed the struggle for the independence of Poland on their banner. After the slogan of self-determination became a smokescreen for social-patriotism, the representatives of Polish Social Democracy struggled against its adoption by the RSDLP in their programme of 1903. Although this happened anyway, the SDKPiL joined the party as a whole in 1906 when, on the one hand, our decisive victory over social-patriotism reduced the risk of it invoking this point of the RSDLP’s programme, and on the other hand, the revolutionary mass struggle made it imperative for all ranks to come together despite all differences of opinion. Moreover, it was possible to do this because this point of the programme played no role whatsoever in the agitation of the RSDLP during the revolution, because we had our own representatives in the central organ of that Party, and because we enjoyed the utmost autonomy in our agitation. In the period of counter-revolution, the national questions in Russia took on a great political significance, and so consequently a discussion began on the position of Social Democracy, and the Polish Social Democrats elaborated their position on these questions extensively.

We have justified and developed this position in general in these theses. We applied this position to the Polish question in a special resolution in September 1915, which we attach here to show concretely how, in our opinion, agitation from a social-revolutionary perspective among the workers of oppressed nations can be carried out.

III. The Polish Question and Social Democracy

1. The attitude of the property-owning classes during the world war showed with terrible clarity the truth of the claim of the SDKPiL that the development of capitalism has splintered the interests of Polish capitalism into opposing fractions and bound them to the interests of the dividing powers. This burial of the struggle for independence found its expression in the conscious renunciation of the slogan of independence among the Polish bourgeoisie. Their entire war programme is to be realised not only by military violence of one or the other imperialist camp, they even strive to strengthen one of these camps by uniting the Polish territories within it. All of the war programmes of the Polish bourgeoisie are directed against Polish independence.

The world war has proven that the period for creating nation states in Europe is over. In the imperialist period of capitalism, every state aims to expand its borders through annexations and the oppression of foreign nations. The attitude of the Polish bourgeoisie in all the partitions [Austrian, German, Russian] has blatantly shown that the ideal of the nation state in the imperialist period is an anachronism, and confirms the validity of the stance of the SDKPiL on the aspiration to independence.

The Polish proletariat has never made national independence its objective. It arose on the basis of the capitalist unification of all three parts of Poland with the partitioning states and carried out its struggle for democracy, for the improvement of the economic situation, for socialism in the framework of historically existing states along with the proletarians of all other nations. They sought to destroy not the existing state boundaries, but rather the character of the state as the organ of class and national oppression. Today, in light of the experience of the world war, the adoption of the slogan of independence as a means of struggling against national oppression would be not only a damaging utopia, but the denial of the simplest foundations of socialism. This slogan would mean striving to create a new imperialist power, a power that would itself strive to subjugate and oppress foreign nations. The only result of such a programme would be the weakening of class consciousness, the exacerbation of national contradictions, the division of the forces of the proletariat, and the amplification of new dangers of war.

2. The programmes of unifying the Polish lands under the rule of one of the imperialist states or a coalition of them, programmes like the one drawn up by the Polish Austro- and Russophiles, arise among the Polish bourgeoisie from the will to strengthen their own position vis-a-vis the bourgeoisie of the partitioning powers, in order to secure themselves a greater proportion of the imperialist loot of the state.

Among the partitioning powers, the tendency towards the unification of the Polish lands gives rise in turn to both strategic and general imperialist interests, which require an extension of the national territory. Born out of the imperialist interests of the bourgeoisies in power in both Poland and the partitioning states, the unification of the Polish lands under the rule of a great power or a coalition of great powers could only be an instrument of imperialist policy. Because these imperialist interests, both general and specifically economic, require the Polish lands to be kept in total submission, they cannot allow for a democratic system in these territories. Therefore there can be no talk of such a unification providing even the minimum guarantee of free social development, the only aspect of the national question linked to the interests of the proletariat.

Whether the war will lead to the unification of the Polish territories into one organism that will be affiliated with the victorious state will depend on the military result of the war and the diplomatic situation that arises from it. The war could also end with the tearing apart of Polish lands through new annexations and the new division of the map of Poland. Indeed, the fears that these new divisions and the changes to the market, customs and legal conditions caused by them could strangle the capitalist development of Poland, and with it the socialist movement of Congress Poland, are exaggerated. Poland’s relatively high degree of economic development has already created productive forces that can adapt to new conditions, and the fact that the socialist movement in one part of Poland would grow weaker is compensated for by the fact it would gain strength in others. However, the necessity for such adaptation would cause a long economic crisis, whose entire brunt would lie on the back of the proletariat.

What we have stated above relates to the idea of creating an independent buffer state which, incidentally, is a hollow utopia for small, powerless groups. In reality, this idea would mean creating a small Polish rump state, which would be the military colony of one or another superpower bloc, a football of their military and economic interests, a territory of exploitation of foreign capital, and a battleground of a future war.

3. From this it follows that the interests of the proletariat – economic, cultural and political alike – preclude all support for the war programme of the Polish bourgeoisie. The old proletarian politics that were determined by the class interests of the proletariat must remain unchanged, and the working class has not the slightest reason to abandon them in favour of any bourgeois war programme. Support for such a programme, which has no real utility to justify it, would mean abandoning independent class action, entering into an alliance with the bourgeoisie during war time, and ultimately derailing the tactics of the proletariat for many years to come. On the other hand, the proletariat cannot accept the defence of the borders of the partitioning states, because in the current era, every capitalist state has become an obstacle to development, not to mention the fact that for the Polish proletariat, the partitioning powers were an organ not only of class oppression, but of national oppression as well.

Without closing their eyes to all the dangers highlighted above which arise for the proletariat in the event of a new partition of Poland, the proletariat must take into account the fact that they cannot be eliminated within the framework of the imperialist epoch, just like all the other dangers of imperialism cannot be eliminated without the victory of socialism.

4. That the general questions that the war has raised cannot be solved, nor the national-cultural interests of the Polish proletariat fruitfully defended in the imperialist era, in no way means that the proletariat must “wait” with folded arms for the advent of socialism to liberate them from the new dangers and burdens of war and from the new dangers of national oppression. Imperialism is the policy of capitalism at the stage of development that makes the socialist organisation of production possible. The sacrifices that the proletariat makes in war, the increased tax burdens, political reaction, the deterioration of working conditions, all of the consequences of war will push the proletariat towards the revolutionary struggle for socialism, which will complete the next historical epoch. The struggle against the war opens up this new epoch. By showing the proletariat how capitalism, which in the name of its own interests sends peoples to the slaughterhouse, tears nations to pieces, tramples national needs, treats the masses like dumb cattle, and by protesting against this waste of peoples’ blood, this arbitrary splitting of nations between superpowers, this doubling down of national oppression, we prepare the proletariat for revolutionary struggle.

Irrespective of whether the exacerbation of the political crisis already allows the proletariat to play an active role during the war, or whether these struggles will only come later, the proletariat will not pursue any separatist policy (the defence of the status quo, the struggle for unification under one power), nor will it chase after the pipe dream of the independence of Poland. They will transform their protests against the consequences of war (blood sacrifice, economic damage, annexations, national oppression) into the struggle against the causes of imperialism. The Polish proletariat will conduct this struggle, as a conscious striving for social revolution, above all in solidarity with the international proletariat, in particular with that of the partitioning powers. This social-revolutionary struggle does not exclude the struggle for the democratisation of political conditions within the framework of capitalism, such as for the abolition of Tsarism in Russia, nor the struggle for national freedoms, such as for the extension of local, provincial and national autonomy. On the contrary, the revolutionary perspective must reinforce the zeal of the proletariat in the struggle for immediate demands, because the consciousness that only social revolution can pave the way to the total abolition of class and national oppression will arm the proletariat against any political compromise that would undermine the class struggle.

Editorial Board of Gazeta Robotnicza(Karl Radek, Mieczysław Broński-Warszawski and Władysław Stein-Krajewski)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.