You are here

Home ›Is the Communist Manifesto Still Relevant Today?

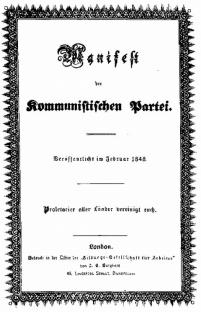

Published almost 150 years ago the Communist Manifesto remains one of the seminal documents of marxist literature. In this article we look at the importance of the Manifesto both as a historical document and in terms of its significance for today.

The Communist Manifesto was published in February 1848 on the eve of the bourgeois revolutions which swept continental Europe. The Manifesto was commissioned by the Communist League, an organisation comprising mainly of exiled German workers which was formed in London in June 1847. At its second congress in November 1847 Marx and Engels won the league over to scientific socialism, i.e. socialism based upon a historical and materialist understanding of society rather than utopian dreams. Although attributed to Marx and Engels the Manifesto was drafted solely by Marx although he borrowed heavily from earlier texts by Engels.

The Materialist Conception of History

The Communist Manifesto is significant from a historical perspective in that it was the first exposition of marxist method to appear in the form of agitational propaganda. This does not mean that the ideas contained in the Manifesto had been conceptualised overnight, rather that they represented a synthesis of empirical observations and theoretical developments by Marx and Engels in the preceding years.

In common with the prevailing trend in German intellectual life in the 1830s and 40s Marx was initially concerned with philosophical enquiry. Hegelian philosophy was predominant and was initially admired by Marx. In contradistinction to previous philosophical systems which sought to discover fixed and eternal truths, Hegelianism was progressive in that it admitted the possibility and necessity of change. Yet Hegel’s philosophy was an idealist one in which human development occurred as a consequence of the dialectical development of ideas as expressed in culture and religion. For Hegel the outcome of the conflict of ideas determined the nature of society. Marx’s radical break with Hegel inverted the Hegelian dialectic asserting that the material conditions of humanity determined the nature of human society ideas. Expressing this succinctly in The German Ideology (1847), Marx and Engels stated:

In direct contrast to German philosophy, which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven. That is to say, we do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life process … life is not determined by consciousness but consciousness by life.

The materialist conception of history as discovered by Marx and Engels conceptualises the dynamic development of human society. As material needs are satisfied through the development of the productive process, so consciousness develops as a reflection of the changes in material circumstances.

This theoretical perspective was arrived through an analysis of the development of human society from ancient times onwards and through empirical observation of contemporary capitalist society. As a young journalist with the radical bourgeois paper Rheinische Zeitung, Marx saw in practice the links between bourgeois property relations and the poverty of workers in articles such as The Poverty of the Moselle Wine Growers. In 1845 Engels had published his Conditions of the Working Class in England, an in depth analysis of the miserable social condition of the English proletariat and the nature of factory production. As living confirmation of the materialist conception itself these empirical observations conditioned the theoretical works leading Marx and Engels to conclude that the class struggle itself is a key determinant to the development of human history.

The Text of The Manifesto

The first section entitled “Bourgeois and Proletarians” opens with one of the fundamental theses of the materialist method by stating:

The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles.

Marx then goes on to illustrate this hypothesis by historical example, the struggle between free-man and slave, patrician and plebeian in ancient society, lord and serf, guild-master and journeymen in the feudal period, and in the modern bourgeois epoch:

Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other: Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.

It is the class struggle which drives history forwards leading to “either a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes”.

Marx then charts the rise of capitalism out of feudal society, how the advances in world trade and new machinery created the financial and technological base for modern industry. He shows the interests of the bourgeois class coming into conflict with the restrictions of the feudal mode of production and the revolutionary role of the bourgeoisie in destroying the old order and finally acceding to state power. In what is almost an aside in the text Marx the essence of the class nature of the state which is still valid today:

The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

Despite the exploitation and misery caused by advancement of capitalism, it is seen as a historically progressive both economically and politically, forging bourgeois nation states out of feudal enclaves, rapidly advancing the productive forces and creating a global economy.

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations put together.

Yet notwithstanding these wonders capitalism is a system riddled with contradictions. There are periodic crises of overproduction which can only be overcome by a massive destruction of the productive forces. Even though capitalism was still in its adolescence Marx observed that “The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them.” It should be remembered that the Manifesto was published almost twenty years before the first volume of Capital and that whilst noting the phenomenon of crisis Marx had not yet developed a sophisticated economic analysis of its causes.

Whilst the advent of crises reveals the fundamental economic flaw in the capitalist system, capital also creates its physical antithesis, a growing class of proletarians who will bring about revolutionary overthrow of the system.

The Revolutionary Class

It is remarkable that much of Marx’s analysis of the nature of the proletariat still holds true today. The Manifesto is an excellent antidote to bourgeois and even some supposedly socialist theorists, who claim that the working class has disappeared. Marx begins by looking at the economic nature of labour and how labour is itself a commodity just like any other to be bought and sold on the market. The proletarians are a class “who live so long as they can find work, and who find work so long as their labour increases capital”. The division of labour in the factory coupled with technological advancement results in a deskilling of labour and a consequent reduction in its price. The bourgeoisie can then reduce its labour costs still further through the employment of women and children.

In addition to economic exploitation Marx describes how the modern proletarian can derive no satisfaction from his work. The worker is merely an “appendage of the machine” carrying out the most simple and monotonous tasks and can have no interest in the product of his labour. The nature of factory production reflects a military hierarchy in which the worker is a “private” of the industrial army, enslaved by the machine, the bosses and their foremen. Marx also shows how in capitalist society the workers are ripped off twice over both as producers and consumers:

No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far, at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by other portions of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker, etc.

As capitalism develops so the proletariat becomes enlarged. The lower middle classes with their diminutive capital cannot hope to compete with large scale production and so these strata sink into the proletariat. Furthermore there is a proletarianisation even of the professional classes:

The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked upon with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.

If this was true in Marx’s day, it is even more relevant today and serves to indicate that the working class is not just comprised of factory and manual workers. Whilst professionals may prefer to think of themselves as “middle class” (which is itself a sociological rather than an economic definition of class) most of them are objectively proletarian.

In the course of its formation the proletariat clubs together to form trades unions in order to defend and advance its interests in the face of capital. Marx saw the importance of the unions in forging the basis of class consciousness. Of course this is not perspective which still holds today as the unions now form a barrier to the development of class consciousness

Marx then asserts the revolutionary nature of the proletariat. Unlike previous exploited classes in history who came to power only to exploit other classes, the proletariat is capable of abolishing exploitation as beneath the proletariat there are no other classes left to exploit.

The proletarians cannot become masters of the productive forces of society, except by abolishing their own previous mode of appropriation, and thereby also every other previous mode of appropriation. They have nothing of their own to secure and to fortify; their mission is to destroy all previous securities for, and insurances of, individual property.

This is a crucial concept which distinguishes the scientific socialism of Marx and Engels from previous thought. Whilst the idea of communism had existed for centuries it has always been based upon the utopian principle of an act of will be well intentioned people. For the first time Marx and Engels can say that communism is an objective historic possibility by virtue of the creation of the modern proletariat embodying the negation of capital.

The Communist Programme

The second section of the Manifesto entitled “Proletarians and Communists” sets out to defend communist principles against bourgeois criticism. The section begins with an outline of the role of communists in relation to the class as a whole and to other working class parties. The communists are distinguished from other working class parties by drawing out the international nature of the class struggle and by always representing the interests of the movement as a whole. At the same time “the communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working class parties”. This is not a formulation which would be valid today but in 1848 capitalism was still a historically progressive system. It was possible for reformists and revolutionaries to fraternally co-exist within the workers movement. At this time revolutionaries would also put forward reformist and democratic demands because these demands were actually obtainable and because communism was not immediately on the agenda. As Marx says, it was still necessary to promote as an immediate aim, the “formation of the proletariat as a class”, a historic process of which reformism was a part. This situation prevailed until the outbreak of the first imperialist war in 1914 when the reformist parties passed wholly into the camp of the bourgeoisie by supporting the war effort in all countries. Since then it has not been possible for reformism to subsist within a genuinely proletarian movement.

However other formulations on the role of communists still hold true. Marx points out that the ideas and principles of communism are not flights of fancy conceived of by intellectuals but are derived from the historic process of the class struggle. The Manifesto stresses that the ultimate aim of the communists is communism, i.e. the abolition of bourgeois property relations.

Marx goes on to defend communist aims against common bourgeois criticisms. In defence of the abolition of bourgeois property, Marx replies that for the majority of the population private property is already done away with. For the workers have no property and the property of the petty bourgeois artisans and peasants is in the process of being destroyed. Marx is clear to distinguish bourgeois property, i.e. capital which is utilised for exploitative purposes, from goods for personal consumption. The aim of communism is to allow all producers to share equitably in what society produces:

Communism deprives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriation.

The Manifesto then deals with the transformation of culture in a communist society and berates the bourgeois intellectual for seeing cultural values as eternal and static rather than a manifestation of the present mode of production:

Your very ideas are but the outgrowth of the conditions of your bourgeois production and bourgeois property, just as your jurisprudence is but the will of your class made into law for all…

The communists do not apologise for wanting to do away with the bourgeois family: “Do you charge us with wanting to stop the exploitation of children by their parents? To this crime we plead guilty”. For the working class there is no meaningful family life anyway and the much vaunted bourgeois family is riddled with hypocrisy, prostitution and adultery lurking behind the myth of patriarchal domestic bliss. The abolition of the bourgeois nation state is defended as “The working men have no country”. In a global economy there is no reason for the existence of the nation state if production were planned in a rational manner. Marx gives short shrift to religious and philosophical objections to communism on the grounds that their proponents are locked within a world view of the existing order:

What else does the history of ideas prove, than that intellectual production changes its character in proportion as material production is changed? The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.

As the communist revolution will be the most radical rupture with traditional property relations it is no wonder that this requires the most radical rupture with traditional ideas.

Tacked on to the end of this section, the Manifesto states that the first step on the road to communism is to win the battle for democracy and a ten point program including nationalisation, graduated income tax, abolition of property in land and free education is set out. This was not meant to be a universal program for all countries at all times. It is specific to the mid nineteenth century when the first historically progressive task was the completion of the bourgeois revolution. Those leftists who today use this section of the Manifesto to justify support for reformism and democracy, whether in the advanced countries or the “third world” show that whilst they are quoting Marx they are not marxist, Unlike Christians who claim that a quote from the bible proves the truth of the quote, for real marxists quoting Marx only proves what Marx said and not the truth of the quote unless it can be substantiated by reference to living reality.

Other Types of Socialism

The idea of socialism existed long before Marx. The third section of the Manifesto entitled “Socialist and Communist Literature” looks at different concepts of socialism which were prevalent in Marx’s day. The first category defined by Marx is “Reactionary Socialism” which harked back to the paternalist certainties of feudal society. Reactionary Socialism was a manifestation of petty bourgeois resistance to the progress of capital and is reactionary as it looks back in an attempt to restore what has become historically redundant. What Marx terms “Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism” has more significant resonances for today. This is the so-called socialism of bourgeois philanthropists and reformers “who want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom”. Bourgeois socialists claim that they are making reforms for the benefit of the working class whereas in reality they are for the benefit of the bourgeoisie. The third type of socialism defined by Marx is “Critical-Utopian Socialism”, the “socialism of St. Simon Fourier and Owen. This type of socialism stemmed from the dawn of the industrial age when the nascent working class was too small to be capable of acting as an independent class. Utopian socialism claims to be above class antagonisms and eschews political and revolutionary activity, relying on the moralistic view that society would be better if only everyone adopted socialist principles. The irrelevance of this type of socialism is demonstrated by the fact that the Owenites in England opposed Chartism which was arguably the largest independent working class movement in English history.

Completion of the Bourgeois Revolution

The final section of the Manifesto deals with the relationship between the communists and the radical bourgeois parties. This section must be viewed in its historical context as a tactic for pushing forward the completion of the bourgeois revolution. Marx had high hopes for the imminent bourgeois revolution in Germany where the capitalist mode of production and the proletariat were far more advanced than had ever been the case in the previous revolutions in France. It was therefore appropriate to support the bourgeois parties so far as they were against feudal reaction. Such support would be entirely contingent and the communists would retain their independence so that the proletarian movement could still struggle against the bourgeoisie. This section was formulated for the specific circumstances of the time and illustrates the historical method of marxism. However as the bourgeois revolution has been completed worldwide there can no longer be any historic justification for such alliances today as there are no longer any progressive sections of the bourgeoisie.

The Manifesto as Document for Today

The Communist Manifesto is still inspirational as a succinct explanation of the marxist method and moreover as an argument for the necessity (but no inevitability) of communism. The twentieth century experience of imperialist war and prolonged economic crisis has confirmed capitalism’s historical limitations and that a revolutionary transformation of society is now more necessary and objectively possible than it was in Marx’s day. Contemporary circumstances demand different tactics to those prescribed in the Manifesto which in this regard was clearly and necessarily a product of its time. This was recognised by Marx and Engels who wrote in the preface to the German edition of the 1872 that whilst there had been many changes in the preceding twenty five years the general principles set out in the Manifesto are “on the whole correct.” However they continue:

The practical application of the principals depend, as the Manifesto itself states, everywhere and at all times on the historical conditions for the time being existing and, for that reason no special stress is laid on the revolutionary measures proposed at the end of section II (the ten point reform program referred to above).

Writing in 1872 Marx and Engels witnessed the experience of the Paris Commune. This proved that the working class could not “simply lay hold of the ready made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes”, as the Manifesto had implied. In new circumstances Marx and Engels understood that it was necessary for the proletariat to destroy the bourgeois state. Other historical developments have also had major consequences for the political activities of revolutionaries. The essence of the marxist method as set out in the Manifesto is to grasp the implications of change for revolutionary theory and practice. Whilst our contemporary perspectives for struggle could not have been envisaged in the Manifesto its concluding lines are as pertinent now as they were one hundred and fifty years ago:

Let the ruling class tremble at the Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to loose but their chains. They have a world to win.

WORKERS OF ALL COUNTRIES UNITE!

PDB

Revolutionary Perspectives #2

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.