You are here

Home ›The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution

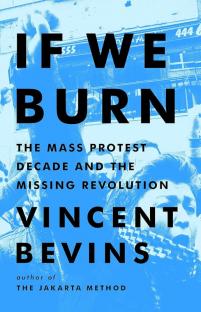

The last decade was marked by an international wave of mass protests – according to some studies, the largest the world has ever seen.(1) In some countries governments came tumbling down, in others repression put an end to any dissent, while elsewhere the movement simply petered out. But nowhere did the protesters get exactly what they wanted (difficult as that is to ascertain considering the sometimes contradictory demands being raised). The new book from the US journalist Vincent Bevins, If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution, attempts to examine why this was the case.

The title of the book is itself a reference to a slogan that appeared on the streets of Hong Kong in 2019 – "if we burn, you burn with us!" (in turn taken from the 2014 film The Hunger Games).(2) Bevins points out that a "decade" is just a construct, but it provides a convenient scope for the book. The story begins in Tunisia in 2010 with the the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, which triggered a domino effect across first the region and then the world, and ends in 2020 with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which for a time put an end to conventional forms of street protest. Over 4 years, Bevins conducted 200 interviews in 12 countries, with both protesters and politicians. He asked what led to each protest movement, what were its goals, were they achieved, and if not, why not, and what lessons could be drawn from the experience.

The anti-austerity movement in Greece, the indignados in Spain, as well as the Occupy movement, all get a mention but Bevins’ main focus is what happened outside the so-called "First World" – in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, Turkey, Ukraine, Hong Kong, South Korea, Chile and particularly Brazil (where Bevins worked as a foreign correspondent for the Los Angeles Times). In our publications and on our website, the ICT wrote about many of these movements as they were developing at the time.(3) And we completely agree with the need for "reflecting on the past and grasping at the future" (p.7), which the author attempts to do in just short of 300 pages.

"The people want the fall of the regime" – slogan of the Tunisian revolt

Bevins doesn't hide his left-wing leanings, but he is no Marxist. Neither, as he admits, is he a historian. He interprets the mass protests of the last decade primarily through the lens of a journalist – the role of media and new technologies take centre stage in the narrative. Other aspects of the question – the class composition of the various protests, the impact of the 2007/8 financial crisis on their genesis, etc. – play at best a secondary role here. While he stresses that no two protests were exactly the same, his framework inevitably produces an emphasis on organisational forms over the class content of each movement.

The bulk of the book consists of a, more or less chronological, retelling of the various protests – a brief summary of the most recent history of each country, an explanation of the political forces at play, the initial spark that gave life to the movement, how the protesters organised themselves, and what the media made of it. The anchors for each story are the real-life participants that Bevins interviewed – Mayara in Brazil, politicised by the "anti-globalisation" movement and anarcho-punk; Hossam in Egypt, a "revolutionary socialist" who set up a popular blog on the internet; Artem in Ukraine, a graduate who tried to unionise at his fast food job; and many more. They help to provide a bit of an insider's view of the dynamics of each protest but don't necessarily give a representative view of the millions who took to the streets (the interviewees tend to be primarily young or at least media savvy individuals, some with already established political or academic careers). Overall this approach makes up for quite a scattered and disjointed narrative. The majority of the book consists of vignettes, interspersed with Bevins' own autobiographical anecdotes, which hammer the point home that most of the protests had unforeseen consequences for the participants. It is in the final two chapters that Bevins draws a balance sheet.

The conclusion he arrives at, hinted at throughout the book, is that the very nature of these protests – horizontally structured, digitally coordinated, leaderless – allowed not only for a “tyranny of structurelessness” to emerge, as once described by the US feminist writer Jo Freeman(4), but also for reactionary political forces to take advantage of the energy unleashed on the streets for their own ends. In many cases, the protests led to the strengthening of populist, nationalist, military or religious organisations (Bolsonaro in Brazil, Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Pravy Sektor in Ukraine, Houthis in Yemen, etc.). Bevins doesn't completely disregard spontaneous protest, which he says will play a part in any uprising. But drawing on Marx and Lenin, and also the US sociologist Charles Tilly(5), he asserts that movements that cannot speak for themselves will be spoken for – so you have to create formal organisations that allow for the exercise of collective action before there is an explosion. He points out that most of the protesters he spoke to, after reflecting on the last decade, admitted they did not think about the endgame (p.259), wished they had “studied revolutionary history more deeply” (p.269) and in effect have since moved closer to classically "Leninist" conceptions. (p.266) They realised “there is no such thing as a political vacuum”. (p.263)

On a surface level, there is much to agree with the conclusion reached by Bevins. Our tendency has always stressed that "without the revolutionary party, every revolt will exhaust itself within the system".(6) But the way "Leninism" is evoked throughout the text poses a problem.

"The spontaneous development of the working-class movement leads to its subordination to bourgeois ideology" – Lenin, 1902

Bevins draws a dichotomy between "horizontalist" and "Leninist" approaches. In this way, "Leninism" becomes a simple synonym for discipline and organisation – "as an organisational philosophy, ‘Leninism’ can be adopted by groups of diverse ideological stripes" (p.17). He just about stops short of describing the Muslim Brotherhood or the Pravy Sektor as "Leninists". But this is to decontextualise Lenin. Bevins claims the "Russian revolutionary leader was obsessed with discipline and secrecy" (p.240), when in fact Lenin never proposed such an approach as some eternal principle. He was formulating tactics in response to the constraints imposed by the Tsarist regime and the particular state of the Russian workers’ movement at the time, conditions which had already evolved by the time of the 1905 revolution:

The basic mistake made by those who now criticise What Is To Be Done? is to treat the pamphlet apart from its connection with the concrete historical situation of a definite, and now long past, period in the development of our Party. ... What Is To Be Done? is a summary of Iskra tactics and Iskra organisational policy in 1901 and 1902. Precisely a “summary”, no more and no less.(7)

But we have addressed all this before.(8) The other issue is Bevin's lack of critical investigation of basic political terminology when it comes to socialism/communism. He variously talks of "the very radical Marxist-Leninist tradition" (p.285), of "Gorbachev, a true believer in the socialist project" (p.27), of "Communist China" (p.191). Taken at face value, he seems to buy into the old Stalinist myths. Which raises the question of the author's politics.

Bevins seems to be on the fence. In the case of Brazil, he clearly has sympathies with both the activists of Movimento Passe Livre, who organised the initial protests against the rise in cost of public transport, as well as the politicians of Lula’s Partido dos Trabalhadore, at the time the ruling party in Brazil (and today once again in power). It's never quite clear if his recommendations are intended for those aiming for a successful revolution, or successful reform, or both. Nor is it clear what Bevins thinks the protests should have achieved or what a "better world" would actually mean. The examples of formal organisations he provides at the end – political parties and unions – gives the impression that, when all is said and done, maybe instead of unruly protesters he'd rather the return of old school social democracy. The irony is that the likes of Tsipras, Iglesias, Corbyn, Sanders or now Boric can be criticised on the same basis – what did they achieve? Except for redirecting the energy unleashed on the streets into avenues safe for capital…

"The condition of the working-class is the real basis and point of departure of all social movements of the present" – Engels, 1845

Bevins argues mass protests took off in the 1950s and 1960s thanks to the emergence of mass media. Of course the arrival of first television, then the internet, and finally social media and instant messaging apps, has changed the scale of how people respond to perceived injustices (which can now be observed in real time). But mass protest has a much older history, and it forms just one tool in the arsenal of the working class movement. On this note, Bevins laments the fact strikes are no longer the go-to form of dissent. And while he's right that the increasing individualisation of society under capitalism fosters particular forms of organising over others (e.g. digitally coordinated spectacles over real workplace activity), the missing piece here is the defeats endured by the working class over the last 50 years. The attacks on working conditions and the economic restructuring of the 1970s and 1980s, a capitalist response to the crisis of profitability, had an enormous effect on the composition of the class and its ability to fight back. We are only now slowly seeing a revival of workers’ struggles, even if still at the level of economic resistance. Which political ideas come to resonate is still up in the air. The question of what we are fighting for is just as important as how we are fighting for it.

The reason the working class, rather than a diffuse mass of protesters, is the revolutionary subject, is due to the role that workers play in the reproduction of capital. At times Bevins comes close to grasping this – “unless society actually ground to a halt, and the reproduction of the economic system became impossible, the institutions could survive” (p.80) – but the intended audience of his book is still activists, rather than the working class. We often repeat that the working class has only two weapons, its organisation and its consciousness. In this sense, Bevins is right about the lack of organisations which could serve as political reference points for new movements. But the question still remains – what kind of movements, what kind of organisations and what kind of political programmes? Bevins has no answer to this.

Anyone who in one way or another lived through the mass protests of the last decade, will find something to relate to here and some pertinent observations are scattered throughout the book. Ultimately however, looking at organisational forms is not enough by itself. The working class needs its own organisations but it also needs its own political alternative. In order to put an end to capitalism – and the wars, the crises and the environmental disasters it produces – the working class has to consciously take up the fight for a stateless, classless, moneyless society. What we wrote over four years ago, a few months before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, remains just as relevant today:

DyjbasHow to make sense of these mushrooming mass protests-cum-rebellions which have no clear class character, owe their lightning speed of organisation largely to the rallying capacity of social media, which have few distinct or established leaders and whose often contradictory demands are constantly changing and are now emulating each other? … The truth is that capitalism now spells disaster and declining life opportunities at every level. The current protests are a symptom of the malaise. In and of themselves they cannot come up with a solution. … But if a new world cannot come about simply through demonstrations, civil disobedience or other actions to pressurise the representatives of the capitalist class to act against their own interests, it is our task — i.e. those of us who are already politically organised internationally — to find a means of intervening in the social ferment to put forward an internationalist, class perspective. This, without any illusions about being able to change the direction of current protests, but with the perspective of having an organised presence in the wider struggles yet to come.(9)

Communist Workers’ Organisation

February 2024

Notes:

(1) Bevins cites the study The Age of Mass Protests: Understanding an Escalating Global Trend, CSID Risk and Foresight Group.

(2) The film was an adaptation of a series of youth adventure books, see: leftcom.org

(3) See e.g. the tag “social unrest” on our website: leftcom.org

(4) The essay, written in the early 1970s, can be found here: jofreeman.com

(5) Among others, he co-authored Dynamics of Contention (2001) and Contentious Politics (2006), influential in the field of social movement studies.

(8) Most recently in our article about Lenin and Leninism: leftcom.org

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.