You are here

Home ›The Colombian debt: a manifestation of the international crisis

The following article has been translated from Prometeo, the theoretical magazine of our Italian comrades in the IBRP, the Partito Comunista Internazionalista (Battaglia Comunista). Note that $1 is approximately 2600 Colombian pesos.

In the last ten years, the Colombian government has tripled its debt without this meaning the modification of its infrastructure or even the minimum improvement in the general standard of living of the population. In the meeting of the Banco Americano de Desarrollo (American Bank for Development) held in the second week of March, it emerged that the per capita income in Colombia had increased by less than 5% in the preceding 10 years, while in Argentina, Costa Rica, Brazil and Bolivia it had increased by between 17 and 27%. (1)

The population and its labour-power, compulsorily placed under distraint by the banks, have been given up as security. In the capitalist economy, the boss class and its state impose on each member of society a share of this class’s infamy: without having ever entered a loan agreement and having paid all their dues, all the inhabitants of the country - from the newborn baby, through the poverty-stricken who wouldn’t even recognise a 10 000 pesos note, through the austere family father who has never been in debt, up to the financial agent who has had tens of millions of dollars in state transfers - all owe the international banking system thousand of dollars and the interest accruing. Those who have to cover the debt with their own bodies are not the ridiculously small 2% of the population who are the sole concrete and direct beneficiaries of the debt, but the 76% who know nothing but super-exploitation, the state’s bullets, unemployment and the pitiless usury of the bankers and businessmen. Without ever knowing the benefits and services promised when the rulers contracted the debt, without ever having visited the streets of Paris, New York, Tokyo, Madrid or London, every inhabitant of this country is a debtor.

While the benefits of the prosperity based on the debt are enjoyed by very few, the sacrifices connected to the debt - and to the war, which today is extending across this martyred territory - are imposed on the whole society. (2)

In this context, the left operates as the reasonable alternative to the bankrupt neo-liberal administration and the IMF/World Bank. Through inertia, its present functionaries always limit themselves to explaining to the avaricious bourgeoisie the paradoxes of its present situation: although to practice an economic and social policy a fiscal balance is necessary, seeking fiscal balance on the basis of spending cuts and tax increases, totally excluding a debt moratorium and the use of a fraction of the expenditure to stimulate growth and the aggregate demand, is utopian. For the left, capitalism is not just economics, but politics: the government’s measures should not just aim at healthy money and a fiscal balance, but also at growth and employment. The left has grown hoarse in shouting for a Keynesian solution to the crisis, consisting of raising aggregate demand and assigning to saving and investment the role of the fundamental motor for growth. Its formula consists of the injection of extraordinary resources into sectors which have a great capacity to generate employment, through the normal mechanisms of public and private investment, without excesses which could exacerbate inflationary pressures. The left threatens capitalism’s orthodoxy with anarchy by stirring up the spectre of revolution, if capitalism doesn’t listen to the left’s theses for containing this anarchy.

The debt and social policy

The component parts of the debt should be called pauperisation credits. If the government successfully completes the socialisation of the debt, the recipes of the IMF will be repeated, which consist of robustly achieving a stabilisation from the fiscal point of view and its consequent structural reforms. (3)

This means deepening the liberalisation of business, the deregulation of the banking sector, the privatisation of state concerns, the reduction of taxes on capital, etc., and increasing the tax burden on wages and consumption. In addition to all this, the reform of pensions is proposed [in a country which is not experiencing demographic aging, or, at least, not to the same extent as in Europe - editorial note], as well as an increase in deductions for social security and a new order in public services (water, gas, electricity, etc.) which guarantees monopoly profits. Overall, these measures belong to the oligopolistic structure of capital on the local level and the subordination of economic processes to the mechanisms of “financialised” capital on a planetary scale. The direction of capital’s political economy clearly shows that national administrations do not set themselves the task of maintaining a level of demand adequate to best utilise the capacity of the economy and to orient it towards the aims of “full employment”, but to guarantee the speculative income of capital. The repercussions of this are visible and are present in all the relations of economic institutions: loss of wages’ purchasing power, dearer and reduced public services and growth in the percentage of absolute misery.

The Colombian economy is tending to go more and more downhill, the unemployment rate of 20.4% and the under-employment rate (part-time working) of 31% are tending to increase, the construction industry is at rock-bottom and the fundamental statistics for consumption betray a profound depression in the internal market. Many interpret the present economic situation as a result of a lack of liquid capital, which is presumed to originate from private spending insufficient to utilise the available productive capacity. This forgets the profound motive for the reluctance of individuals and companies in increasing their spending, no matter how much money they have and despite the conventional monetary policies which, as is happening in Colombia, and despite registering annual increases of up to 35% of the means of payment, achieve no stimulating effect.

Other bourgeois analysts admit that the recession is not due to accidental factors, but deny its international character and maintain the anachronistic distinction between an “internal crisis” and an “external crisis”, which is far from conceptually representing the present structure of capitalism. They attribute the right cause to its effects: the reduction of the aggregate demand, which determined the policy of high rates of interest, retrospectively revised; to the indirect taxes; to the fixing of wages below the expected rate of inflation; to the reduction of public spending in general and, in particular, of social spending, all with the aim of drastically reducing the fiscal deficit. They did not see this combination of phenomena - all stemming from the outside, so far as they referred exclusively to the field of pure consumption (effective demand) or to government policy - as part of the financialisation of the economy. The final cause of these phenomena and these measures lies in the crisis of the cycle of accumulation of capital on the world scale, within the international circuit of reproduction. Nevertheless, the country’s credit rating is described as “negative”. (4)

Despite the IMF guarantee, the capacity of the state and the economy to pay is doubtful. Considering that the value of the deficit is 4.6% of the gross national product as predicted by the government, many are alarmed by the growth of the debt being considerably greater than that of the economy. According to a parliamentary paper

the ratio between the central government debt and the GNP increased by 212% between 1994 and 1999. In 2001, the internal debt increased by 13% in real terms. In its turn, the external debt was augmented by 18% in real terms, which means it increased at a rate 12 times that of the GNP.

This rate of indebtedness is unsustainable. A figure which grows at 18% will double in four years. If this dynamic is maintained, the external debt will be unmanageable in the short-term and will end in a financial collapse. Regarding the calculation of the gross government debt - including departmental organisations - there are discrepancies between the government’s supervisory organisations. Which the so-called Council for Fiscal Policy (Confis) says the debt amounts to 58% of GNP, 110 trillion pesos, the Contralor Generale de la Republica (CGR) indicates that it has reached 68% of GNP.

The vertiginous increase in the debt in recent years, destined in large part to cover current expenses, has led to comparisons between the fiscal situations of Colombia and Argentina, although the ratio between the national debt and the GNP of the latter reached 46% at the end of 2001, much lower than in Colombia’s case. In fact, despite the fact that there has been an adjustment, the national debt continues to show a tendency to increase. The essential point is that the state returns to contract new credits - which means more debt - in order to pay the debt; in this way, the dynamic generated by the government’s needs ensures that the weight of the debt becomes ever greater for the government itself. For example, this year the government must obtain $300mn in treasury bonds to satisfy external finance, and, in this regard, the Finance Minister is preparing to contract a tied loan of $250mn. The background to this situation is to be sought in the disequilibria in the budget and the balance of payments, as well as in the historical accumulation of a debt of 5% of the GNP. Amongst other things, the increase of the debt implies that the interest payments grow more quickly than they are amortised, sharpening the middle-term difficulties and swallowing the greater part of the resources. According to Mauro Leos, of the North American risk assessors Moody’s, in his interview with the El Tiempo newspaper, 7th April 2002, Colombia “has the highest relative debt and debt payments”.

A CGR study shows that Colombia has transformed itself into a net exporter of capital over the last two years. Which means that the resources that the country receives in the form of new loans is less, by $300mn, than what it pays in interest and to pay off old loans. This year, for example, the nation turned over $2864mn to external creditors, and it is expected that a similar amount will be borrowed. “This year the government will receive from external creditors financial resources equal to the payments of interest and amortisation. For this reason, external credits will not be covered by printing money”, according to the declaration of the director of Public Credit for the Ministry of Finance.

However, it is not just the external debt which cause the torment, but the internal one too. The government owes the banks, through the so-called Treasury Titlse (TES) the fine sum of 61 trillion pesos of gross debt. A striking proof of the narrow straits in which the state finds itself in honouring its creditors is the plan for re-contracting the debt, which consists in the exchange of titles which are nearly due for ones with a much longer term. “In this way it succeeded in postponing the payment of $500mn to internal investors. The same thing was being prepared for external investors, but the attack of 11th September on New York reduced this opportunity for the Finance Ministry”. (5)

The risk is so distressing that the Confis admits that the state is breathlessly searching for money in the form of loans with the sole objective of paying the debts which are due. The CGR and other private and public entities are warning that the situation is unsustainable. This year, the government will have to pay off capital sums and interest relating to the internal and external public debt amounting to 23 trillion pesos, or 1.9 trillion pesos per month.

At the gates of financial collapse

The opinion of Confis is that, to avoid arriving at situation of moratorium like Argentina, with the risk that all the doors of the international banking system shut, it is necessary to avoid the debt assuming dangerous levels. According to it, “the national finances must begin to arrive at a gap in the budget of between 1% and 3.5% of GNP from the start of next year. And the economy must grow at 4.5% in real terms”. (6)

But the economic “growth” of 1.5% registered last year is anaemic. To have a perspective in capitalist terms, it is indispensable that a country increments its total production with a rhythm at least equal to demographic growth. When production increases at a rate inferior to that of the population, as happened in 2001, a fall in the pro capita production is registered, which is a euphemism for pauperisation.

The big problem is that the state, given the present situation, is able to contribute very little to this situation, neither in terms of the budget, nor in terms of growth in the GNP. Because of the great size of the outgoings in capital and interest payments which contribute to the budget, and because of the severe controls on spending, state investment has noticeably declined. This year, the outgoings for investment in the National General Budget (7) just reach 9.9 trillion pesos, in comparison to the 23 trillion destined to cover the debt. Of this 9.9 trillion, they are preparing to cut at least 2 trillion to use on military spending. At the first sign of increases in the spending caused by the war and the consequent deficit, the investors and the markets react by speculating on the titles of the internal public debt - the interest rates on the TES have increased by 170 points (i.e., 1.7%) - and national treasury bonds (which are due in 2012) are beginning to trade abroad at 92% of their nominal value, or even lower. This meant a loss of between $85 000 and $90 000 for every million dollars invested. Taking the increase in the country’s risk premium, external investors began to sell their Colombian titles. Just a week after the government’s declaration of war, these titles suffered a loss of 4%.

On the other hand, the pressure of the debt obliged the government to adopt counterproductive measures to rectify the deficit. In its intention to decelerate the growth of the debt, the principal rescue mechanism which is left to the government consists of augmenting the price of public services, but doing this, in its turn, obstructs the desired economic growth and lowers competitivity. In respect to this, various initiatives have been proposed: printing new “war bonds”, resorting to the constitutional mechanism of an “economic and social emergency”, which would allow the government to resort to the credits of the bank of issue (i.e., to print money), which is presently prohibited by the constitution, or, following the recommendations of the IMF, to obtain from Congress the extraordinary resources needed, to avoid emergency measures which could endanger the fiscal adjustment.

In the public service sector, they are implementing a system of charges which allows the bodies to put into effect increases in charges above inflation. It is a system which in fact constrains the lowest social sectors to suffer the greatest part of the cost of the service, without considering that they pay a greater proportion of their income for the service. This is one of the reasons why the price index for these social strata grows more quickly than that for higher social strata. By this policy, they wish to reduce even more the “returns” of labour with respect to capital and to obtain a monopolistic profit at the expense of the creation of real wealth. In March, the so-called Commission for the Regulation of Energy (CREG) proposed establishing of energy tariffs allowing the energy firms to obtain a return of 12 - 14%. (8)

It is well-known that the make-up of these concerns means that they have an extremely high organic composition, which translates into a low physical profitability. In normal circumstances, they are not in a position to operate with industrial and commercial rates of return. In fact, the levels of returns indicated for the CREG can only be obtained through monopolistic procedures aimed at setting prices at an exorbitant level and obtaining large speculative gains. The best example of this is at present given by Codensa. The present profitability of this concern bumps along between 2% and 3%. Its managers demand that, in order to continue to operate in the country they need to be guaranteed higher returns. It is not at all surprising that its plans to improve its books are not aimed at elevating productivity or reducing costs, but at lowering the firm’s capital to 1.2bn pesos. The complementary action of the government comes from the government, which has announced an increase in energy prices of 25%. In both cases, it is a question of artificial mechanisms which push up the profitability of the firms’ capital at the cost of the general decline in workers’ wages, through the augmentation of tariffs above the rate of inflation and the market valuation, and replacing capital by credits at rates lower than the profitability established by CREG. In fact, the firms are enabled to obtain large profit margins with a reduced capital. This practice implies a high cost for the economy as a whole and for the waged population: the increase of the tariffs beyond the rate of inflation means reductions in real wages. (9)

Moreover, the de-capitalisation of concerns to return capital to its origin causes a fall in internal saving: the capitals which are withdraw are replaced by internal or external credits which could have been used for other purposes.

The government’s political principals in facing the debt apply to the budget deficit. In this regard, the solutions found can be summed up as being the adoption of measures which reduce expenditure and those which generate new income. The Colombian state’s problem is that, although it has successfully increased its income through excise and revenue reform (increasing it by a further two points of the GNP), at the same time it has increased its expenditure. For all that the annual rate of growth of acquisition of public debt has been reduced in the last two years from 26% to 7%, the increase in the obligations to international creditors has progressed geometrically. It is so great that the remittance for the payment of public debt and interest thereon underwent a jump from 528bn pesos in 1990 to 1.5 trillion in 1993; afterwards, it reached 7.1 trillion in 1997 and doubled to 15.3 trillion in 2000. This year it will leap to 23 trillion. In addition, but by no means is this all, the economic recession is seriously hindering the government’s new projects for fiscal adjustment. Any adjustment necessarily implies a negative social settlement. With a decrease in the GNP of close to 7% in 1999 and the low increase in the last two years, the global framework is becoming more and more complicated for the Colombian state. The generalisation of the internal war and the consequent augmentation of military spending (10) - which today absorbs a little more than 30% of the finances destined for the functioning of the state - pose risks and additional problems from the point of view of creditworthiness. For the moment, we know that the government needs a million dollars more to sustain military expenditure. (11)

Another factor is the enormous corruption, the cost of which, according to a recent World Bank report, is greater than the destruction of the war in terms of impact on the economy: while war damage constitutes 4% of GNP, corruption reaches 7.9%, money which in the main flees the country through money laundering. (12)

Nor can the influence on the dynamic of the debt of the fall in exports, which started with the so-called “opening of the economy”, be omitted. Firstly, the “opening” - because of an industry rendered inflexible by more than 30 years of “hothouse”, that is, highly protected, economy, which was dominated by oligopolies which exploited the market as if it were a private fishing reserve - manifested itself in a structural deficit in the balance of payments and, secondly, it was financed by interest rates higher than the growth in GNP. Both these factors determined a heightening of debt relative to the GNP, which can be contained only by recessionary policies which cause the precipitous fall in imports.

The vicious circle is, therefore, clear: the massive ingress of hoped-for capital after the “opening” simply converted itself into a nominal change ownership with a low level of technological innovation - given the presence of monopolistic guarantees and the desire for a rapid return on invested capital - and led to the reinforcement of the centralisation of capital and to the elimination of industrial and agricultural sectors considered superfluous by the world market, or which produced goods at a higher price than elsewhere. Integrated into an international circuit in which finance capital generates uncontrollable movements on a planetary scale, economies became more fragile and remained exposed to recurrent recessions and severe exchange and financial crises. In fact, with the “opening”, there was importation massively above the exportation, and the difference was covered by external credits at rates above 10%. Every year it was necessary to obtain financing to cover the excess of importation and the interest due on previous credits.

At the root of the disaster of the state accounts there is also the increase of internal debt which rests on resources captured on capital markets at rates of 36 and 37%. And, as the interest rate exceeded the growth in production, the ratio between the debt and the GNP increased systematically. Although the attempt was made to correct the disequilibrium between imports and exports by adjusting the amount of money in circulation in accordance to the dictates of the market, no such mechanism worked. And, although Colombia is not at the same levels as Argentina (13), in neither case was the adjustment sufficient to compensate for the relaxation of tariffs and restore the balance of payments. At present, both countries are registering a deficit in their current accounts of the balance of payments of about 3% of GNP, which implies a great increase in the debt.

Some bourgeois analysts of the Keynesian school have drawn attention to the errors in the government’s political economy and particularly as regards the currency manoeuvres. The behaviour of exchange rates in Colombia - revaluationist tendencies relating to the abundance of foreign currency - is not consistent with any real data. Considering that imports are greater than exports and that the distribution of interest-bearing titles for the external debt exceed $3bn,

the abundance of foreign currency can only be justified by government action aimed at drawing capital above the needs of disbursement, either to cover the debt or to armour-plate the economy. (14)

The maintenance of flexible rates generates distorting economic movements. One such is that the broadening of the debt manifests itself in revaluation and the heightening of interest rates.

As is written in the schoolbooks, in these circumstances expansion is achieved through the contraction of the external sector, that is, through the reduction of exportation and the augmenting of importation. (15)

Although the state administrators are frequently reproved for not recognizing this reality, the facts are obscured: they, in the same as economic agents, simply react mechanically to movements and forces which are outside their control. As far as regards the deficit, they are engaged in breaking the process and occupying themselves with the so-called “armour-plating” of the economy with the anticipated contraction of external credits. As if it were logical that it was so, the excessive entry of foreign currency accelerated revaluation, provoking the opposite effect: in fact contracting massive external debt brought with it the revaluation, frustrating exports. (16)

Another aspect of the blind and unconscious process of the economy is the impotence of the technocrats prescriptions. Despite the periodic reduction of interest rates (the discount rate) on the part of the central bank - theoretically devoted to supplying liquidity to the economy - credit continues to stagnate. While in 1998 the portfolio of the financial system stood at 56 trillion pesos, today it is at 46.2 trillion pesos (a reduction of 17%). As well as the recession, this indicates that the revaluation of the exchange rate is giving rise to expectations among economic actors of future devaluations, and these expectations stimulate them to put savings into external investments in order to obtain advantages from the announcement of a devaluation. Nevertheless, Professor Sarmiento and his left disciples are wrong when they maintain that these “errors” would be corrected within a system where the state fixes (and continually reviews) exchange rates, rather than leaving them to the market. This would have been possible before the present globalised and liberalised economy, since governments could relatively independently sketch out the directions of macroeconomic policy. At that time, confronted by situations of crisis and having the aim of achieving budget adjustments, the state could not renounce the possibilities for obtaining credit from the bank of issue at low cost and long term. The expansive effects of credits from the central bank were - as was verified during the financial crisis in the middle of the 1980’s - perfectly manageable and could be compensated for by the use of monetary and exchange instruments to avoid the explosion of inflation. Then, fiscal deficit could operate as a factor to stimulate the economy without significant repercussions on the exchange rate. Sarmiento talks of the “Keynesian heresy” and denounces the induction of a fiscal deficit financed by external credit within a system of flexible rates in an economy with levels of indebtedness like those of Colombia, as “the royal road to financial crisis”. (17)

As an alternative, he proposes covering the hole with internal credit, passing over the immediate inflationary effect that this would provoke within the present economic framework. Subject to the heavy action of international finance capital and to a world supply which is ever more abundant, the economy would not march towards Keynesian “full employment”, but towards a deepening of the local manifestations of the crisis. Today, in fact, the currency and capital markets act through autonomous channels and have a power all of their own which neutralises monetary policies which, in other circumstances, show themselves to be efficacious. The drastic reduction of national states’ regulating capacity in the context of globalisation, the struggle in the centres of imperialist power and the specific weight of their interests on the local level limit the scope of action of the specific national governments. In other words, while for left bourgeois critics the responsibility for the situation falls on the theories which serve to justify the economic model, we see it in the structural conditions of the capitalist economy.

Another explanation for the phenomena in the current account is found in the high dependence on exports of raw materials. Returning to our parallel between Argentina and Colombia, we observe that the consequences of indebtedness are similar in both countries. They are highly unstable economies. The stability of the balance of payments is conditioned by the poor levels of productive activity. The system is becoming excessively fragile and any external perturbation could plunge it into crisis. For example, Argentina could never absorb the large devaluation of its main commercial partner, Brazil, practically the sole importer of its industrial products. Just like Argentina, more than half of Colombian exports are represented by agricultural and mining products. (18)

In such a state the amounts of incoming foreign currencies are relatively rigid with respect to the exchange rate, and excessively high amounts are needed to compensate for the tariffs and to equalise the balance of payments, something which is not always possible. Therefore, the fall in the prices of the principal export products is not compensated by new exportation. If there is not a sustained growth of two deciles in exports, the weight of the debt will be ever more onerous. According to a report given by Senator Luis Guillermo Vélez to Congress, the accumulated deficit in the current account (balance of payments) in the last three years stands at 5%; recall that this year alone there will be a deficit of $3bn, about 3% of GNP. A cofactor - with the restrictions which we mentioned earlier - is the revaluation of the peso at a rate which fluctuates according to the fluctuations of the free market. After a certain point, revaluation is transformed into a recessionary factor which ends by putting the brake on export and causing the plan to fail. The central government deficit is 10 trillion pesos.

(1) We underline the invalidity of general concepts such as “per capita income”. It is a question of a conceptualisation which abstracts from the social and class differences between the individuals who live in a territory and divides between them - making a tabula rasa of these differences - the national income.

(2) Declaration of the Industry Minister JM Santos to the El Espectador newspaper, 3rd March 2002.

(3) Among the IMF plan’s priorities are:

- reform of the pensions system;

- a law for a limitation in the growth of public spending and the gradual reduction of the debt;

- reform of the banking system;

- reform of the stock exchange and of the market in moveable goods;

- conceding powers to the executive for the suppression of public bodies.

They are preparing for, amongst other things, the sale of the Banco Cafetero, the privatisation of 14 electrical companies, the franchising of the construction of rail tunnels and of the mobile phone system.

(4) The “credit rating” shows the capacity to pay (or insolvency) of the economy. This is determined by the level of debt, the dynamic of the debt and the behaviour of the investments which are to cover it.

(5) El Espectador, 17th March 2002.

(6) Ibid.

(7) According to the Industry Ministry, the national budget in 2002 was made up in the following way: total working costs: 20 042 680 375 932; service payments on the external debt: 10 030 499 122 261; service payments on the internal debt: 12 909 299 895 668; total service payments on public debt: 22 939 799 017 929; total investments: 9 923 070 844 214; total budget 62 910 550 238 075.

(8) El Espectador, 3rd March 2002.

(9) By fixing their gaze on the GNP and the macro-economic aggregates, the economists have lost sight of the evolution of workers’ incomes. In the last 5 years, the mean real income of Colombian workers has fallen 29%. This fall means that incomes are below those of 1978. The figures for income by age allow a better analysis of the depth of the crisis. The crisis has changed the relationships between age and income. In Colombia, the income level grows in inverse proportion to the age: the older you are, the lower the income. Today, every yearly automatic promotion is paid half of what it was 25 years ago: 0.8 as against 1.4. The fall in pay by age obviously has its greatest effect on the elderly. While, during the last 5 years, the income of the young has fallen by 15%, that of the elderly has collapsed by 35%. Source: El Espectador, 27th January 2002.

(10) The daily war expenditure of the Armed Forces is 45 000mn pesos, and tends to increase to the same extent as the number of professional troops and the technological components of military operations. All this open the possibility of a collapse in public finances.

(11) At the moment, every increase of 10 000 professional soldiers costs the Treasury 260 000mn pesos.

(12) El Espectador, 3rd March 2002.

(13) In this country, internal inflation has grown less than international inflation over the last few years, and, over the last year there has been the introduction of a plurality of currencies which implies a nominal devaluation. At the end of convertibility the real rate of exchange was higher than at the start. Over the last three years there have been various devaluations which have set the real rate of exchange higher than its historical level.

(14) “Induced revaluation”, Eduardo Sarmiento. El Espectador, 27th January 2002.

(15) Ibid.

(16) In 2001, the Banco de la Republica undertook a loan for the record sum of $3.7bn. El Tiempo, 6th January 2002.

The drama is not so much in the fiscal deficit, but in the modality of the flexible exchange rate. This modality was adopted throughout Latin America at the beginning of the decade and the countries cannot adapt to these high rates. Market stimuli generate opportunities for revaluation which accumulate and explode in revaluations. The worst thing is that the system has become perverse. When there is a scarcity of capital, the exchange rate increases, giving life to serious recessionary effects. When there is an abundance of dollars, the rate of exchange is revalued, threatening the stability of exchange. The economies are tossed between recession and exchange crises.

-

... the Pastrana administration... after the tax reform and an agreement with the IMF, ended up having a higher deficit. At present, public spending increases by about 20%. However, this purely monetarist management could turn out to be the worst of all evils.

El Espectador, ibid.

(18) This data shows the industrial regression that has hit the Colombian economy with respect to the 1980’s, during which 65% of its exports were manufactured.

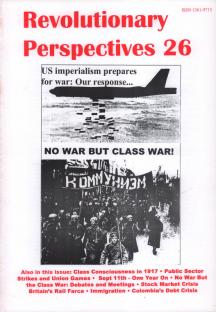

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #26

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.