You are here

Home ›The Clash for Gas - Europeans Shivered while Ukraine and Russia Haggled

If any more proof were needed that capitalism is a less than useful way to provide for social needs the latest clash between Russia and Ukraine over payment for gas was it.

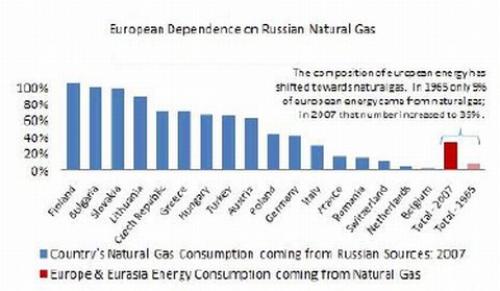

In a repeat of the gas war between the two states in the winter of 2006 Russia’s Gazprom, the world’s largest gas company, cut supplies to Ukraine on 1st January whilst disingenuously maintaining that exports to the rest of Europe via pipelines in Ukraine would not be affected. While the EU as a whole relies on Russia for around 25% of its natural gas consumption, 80% of it coming through Ukraine, some member states such as Finland or former ‘soviet republics’ like Estonia and Latvia and ex-eastern bloc countries like Bulgaria are more or less a 100% dependent on Russian gas supplies. This did not prevent the dispute escalating. As gas pressure in the transit pipes dropped and Gazprom accused Ukraine of siphoning off gas meant for wider export, Naftogaz - Ukraine’s state-run gas supplier - argued that Gazprom itself had cut off supplies. Certainly this is what happened on 7th January when Vladimir Putin, doubling up as Russia’s Prime Minister and chief spokesman for Gazprom, ordered the shutting down of all gas through Ukraine. So, at the height of the winter cold, eighteen European states found their gas supply was either completely cut off or severely disrupted for what turned out to be almost a fortnight.

The impact varied from state to state. Some, such as Austria and Germany, were not so badly hit thanks to their storage facilities and/or alternative supply routes. (Germany, for instance, gets half its gas from Russia but not all of it via Ukraine. Whilst E.ON Ruhrgas warned customers to expect cuts Wingas assured its customers they would not be affected because its supplies from Russia come via Belarus and Poland.) For some ex-Soviet states who are completely dependent on gas from Russia and with no alternative supply routes it was a disaster. In Bosnia-Herzogovina - 100% dependent on Russia and with no reserves - the gas supply stopped even before 7th January. In Sarajevo, where the temperature was -5p, shops sold out of electric heaters within hours and 72,000 households found themselves without any heating. Bulgaria immediately started rationing gas supplies to industry, warning that stocks could run out in a matter of days. Thousands of households in eastern Bulgaria had no gas heating, schools were shut and some companies shut down. Two towns in eastern Bulgaria - Varna and Dobrich - were totally without gas from the start. In Slovakia a state of emergency was declared and both the Slovak and Bulgarian governments toyed with the idea of reopening dangerous Soviet-era nuclear power stations. (At Jaslovske Bohunice and Kozloduy respectively.) And so it was throughout much of the EU. In Ukraine itself, President Viktor Yushchenko insisted that only gas produced inside the country or from underground storage facilities was being consumed. From the sidelines the UK looked on while its energy monopolies took advantage of the higher Continental prices by exporting gas through the Interconnector pipeline to the European mainland. At the same time they moaned that this still hadn’t pushed the price of gas back up in the UK. (Not that gas bills in the UK had come down. Price reductions, we are promised, will be passed on to the consumer once the winter is over (1).)

The EU was careful not to blame either side. In its notional neutral capacity it sent “observers” to Ukraine to find out who was and who wasn’t turning off the gas and Manuel Barroso spent three weeks trying to broker a deal. However, the European Commission was not party to the deal that was finally brokered. When Putin (this time in his role as Russia’s Prime Minister) and Yulia Timoshenko, Ukrainian PM, announced on 17th January that Gazprom and Naftogaz had signed a new 10-year deal which would allow the resumption of gas transit through Ukraine, the EU simply had to accept it even though its full terms remain secret. This is a far cry from the 1990s when, following the collapse of the USSR, the EU expected to have an assured supply of oil and gas from Russia and beyond by means of production sharing agreements between international (i.e. Western) energy companies and cash-strapped Russian firms who had no alternative but to sign up for joint ventures with the likes of Total and Royal Dutch Shell. However, as energy prices (oil and gas) soared between 2004-8, the Russian state, led by Putin, began to implement an overarching energy policy which Russian companies were obliged to keep in step with and which aims to use Russia’s immense “energy power” as a strategic weapon. As with oil deals, Russia began to renege on gas agreements it didn’t reckon were in its interests. Thus, a joint project to develop the Stockman gas field in the Barents Sea was cancelled. In 2006, Putin announced the complete exchangeability of the rouble, the prelude to a longer-term aim of trading gas and oil in roubles instead of dollars. This was a direct challenge to the might of the US whose position in the world owes more to its currency being the overarching unit of international trade than anything else. To this end, the construction of a prestige glass building to house a new ‘bourse’ in St Petersburg for trading gas futures in roubles was announced. It was an indication of the growing confidence of revamped Russian imperialism. In the autumn of the same year EU energy negotiators, led by Jose Manuel Barroso, were shocked to find that Russia would not sign the Energy Charter Treaty which was at the centre of an EU-Russian summit in Helsinki. The Energy Charter’s professed aim is “to develop the energy potential of central and east Europe and ensure security of energy supply for the EU”. For Russia it would have meant more, not less involvement of European companies in gas production as well as giving up its monopoly on pipeline use. But, as Putin bluntly put it:

“What will be the benefit for us? Let’s have something equivalent in western Europe and discuss how we will be let in.” (2)

It’s not that Russia is averse to joint ventures with the EU and European companies. It is simply, as Putin makes clear, whether or not Russian capital as a whole stands to gain. And, as even the most cursory enquiry into gas or oil reveals, the interests of Russian capital as a whole go far beyond the prospect of immediate financial gain for particular companies to the wider economic and strategic political interests the Russian state is impelled to follow in order to survive. As Lenin argued long ago, there is no such thing as a simple economic struggle in the age of imperialism. Today’s struggle for control over oil and gas supplies, which involves a complex intertwining of financial, military, political and economic aims, bears this out remarkably.

The Energy Ties That Bind

At one level, the latest dispute between Russia and Ukraine can be seen as a purely financial wrangle between customer and supplier over the demand that Ukraine should pay the current “market price” for its gas. Part of the deal announced on 19th January was that, after this year, Ukraine would pay for its gas according to the wider European price formula (which links gas to oil prices over a six to nine month time lag). (3) For 2009, Russia has agreed to give Ukraine a 20% discount, whilst Ukraine in turn agreed to retain discounted transit tariffs for Russia. Yet why, almost two decades since the break up of the USSR and over four years since the “Orange Revolution” which propelled Ukraine into the US political sphere of influence, was Russia still supplying discounted gas to Ukraine? The answer is that Russia has been using gas as political leverage inside Ukraine to undermine the pro-Western stance of its politicians as part of a longer term strategy to draw Ukraine back into its own orbit. That policy and strategy is not going to change but economic circumstances have changed lately. With oil and gas prices tumbling, its revenues and the rouble declining and its carefully hoarded currency reserves dwindling, Russia is going to be reluctant to sell gas at discounted prices unless there is substantial political and economic gain.

The situation of Gazprom itself only reinforces this. Though it accounts for 10% of Russia’s GDP it has massive debts of around $60 billion. Further, Gazprom is increasingly finding itself obliged to accept that it pay the market price for gas it buys from central Asia to supplement Russian sources. (Turkmenistan, for instance, has recently been able to up its price to Russia, since the Central Asia-China pipeline that is currently being built will mean that China will be competing for the same gas supply.) In strict commercial terms it now makes even less sense for Russia to be selling gas onwards below the price it is paying for supplies further east. However, there is more to this than straightforward commerce. Despite the impact of the world economic crisis on its own economy, Russia has had some success in undermining US encroachments into what it regards as more or less its own territory. Last year Germany and France, under pressure from Russia, voted against Ukraine and Georgia joining NATO and began to turn the tide of US gains in the area of the old soviet empire. The US failure to prevent Russia from invading Georgia and militarily taking over South Ossetia was an even bigger encouragement to Russian imperialism.

Inside Ukraine, the all-out enthusiasm for the US and the west has worn off amongst the architects of the Orange Revolution. The alliance between Prime Minister Julia Timoshenko and President Viktor Yushchenko has long since broken down. Now Timoshenko has adopted a much more pragmatic stance towards Russia. Unlike Yushchenko, she has shut up about the necessity for Ukraine to join NATO. While Yushchenko gave full support to Saakashvili during the invasion of Georgia, Timoshenko remained neutral and said nothing. Although the precise details are unclear, the January gas agreement she signed with Putin contained at least one clause aimed at reducing the power of Yushchenko and reflecting the merging of interests between her faction and Moscow. Since 2006, gas in Ukraine has been delivered by an intermediary company, RosUkrEnergo, a private business consortium in which Gazprom had a 50% stake. The other main shareholder is one Dimitry Firtash, a business associate and supporter of Yushchenko. In January, Putin and Timoshenko agreed not to use intermediary companies - i.e., to sideline RosUkrEnergo. In addition, apparently, an offshoot of Gazprom (Gazprom Ukraina) will receive up to 25% of the Ukrainian gas market. (4) In Ukraine, the knock-on effects of this have produced a bizarre political pantomime where the offices of Naftogaz have been raided by armed police (under the authority of the President) looking for evidence of gas that legally belongs to RosUkrEnergo. In Poland, the effect is more serious, since its gas supplies from Russia are still being interrupted while a new contract which excludes RosUkrEnergo is drawn up. (5) With elections coming up in Ukraine, it is certain there will be evidence of more Russian involvement. However, whichever faction comes out on top, Ukraine’s dire economic situation will leave little room for manoeuvre. The supposed ten year agreement is hardly likely to last. Sooner rather than later, Ukraine is going to renege on its gas bills and the president of Gazprom knows it. When it does there will have to be further negotiations and this time Gazprom will be demanding further control of gas facilities in Ukraine, including its pipelines - in return of course for a price discount. This is how Russia has used its gas monopoly for political leverage in Armenia and Belarus where, as one commentator puts it:

“Control over the gas transport system was the basis for regulating relations between Russia and Armenia and Belarus. In both countries Gazprom became the owner or shareholder of gas pipeline networks or hydroelectric stations. As a result, Armenia buys Russian gas for $110 per thousand cubic meters and Belarus for $128.” (6)

Given that the price for gas at the time was somewhere between $225-295, this is a substantial concession. In Ukraine, with its large ethnic Russian minority and historical ties, Russia will be looking to regain something of what it lost to the West with the collapse of the USSR. The influence that the West has bought from the money it has pumped into Ukraine one way or another in recent years is being quickly eroded by the economic crisis. There has been a dramatic decline in industrial output (34% year on year in January); the value of the currency has tumbled and now the IMF is imposing impossible conditions on a $16.4bn loan (the budget deficit is to be kept at no more than 3% of GDP) which will mean enormous public spending cuts as unemployment mounts. Next on Russia’s agenda will be the reopening of negotiations over the naval base it rents from Ukraine at Sevastopol on the Black Sea. Ukraine is supposed to be going to kick out Russia when the lease runs out shortly, but who knows what bargaining over the price of gas can achieve.

All this, of course has nothing to do with the situation of the working class in Ukraine who are facing an economic crisis potentially as serious as when the USSR collapsed. At the moment gas prices are subsidised. No political faction in Ukraine can afford to increase fuel prices in line with the “market” price (albeit that this must also go down), but without that Russia’s demands cannot be met. Welcome back Ukraine!

For the EU, last winter’s gas crisis only bolstered the political desire for “greater energy security”. This was possibly a calculation made by Putin and others as the taps were turned off. He claims the crisis has given added impetus to finishing an alternative pipeline, Nord Stream, which will run under the Baltic Sea and take gas from Siberia to Germany and beyond in the rest of Europe. (This is in addition to the existing Blue Stream pipeline the Russians have already got running under the Black Sea through Turkey and back up to Bulgaria.) The project is run by a joint Russian-European company Nord Stream AG, whose shareholders are presided by Gerhard Schröder, the German ex-Chancellor and - apparently a good friend of Putin. By no coincidence, on the same day as Putin ordered the gas supply to Ukraine to be completely cut off, he met with Schröder at the Tavrichesky palace outside St Petersburg and told journalists that the

“current crisis has finally convinced European consumers that the pipeline is necessary and should be completed as soon as possible.” (7)

These words were directed not towards European consumers but rather to the EU’s Energy Commissioners, first to jolt Brussels into persuading Sweden and Finland not to put environmental obstacles in the way of the pipeline and possibly also to prepare the ground for a demand for a capital injection from the EU in view of Gazprom’s investment shortfall this year as the economic crisis bites.

The Russians are also still trying to woo the Europeans with yet another alternative pipeline known as South Stream in conjunction with a subsidiary of Eni, the Italian energy company. The plan is to bring gas from central Asia and Russia to Europe from a compressor station at Bergovaya on Russia’s Black Sea coast, then under the sea to Varna on the Bulgarian coast. From there it will split with a south-western route to Greece and southern Italy and a north-western route through Serbia and Hungary to Austria. - That is, after the pipeline has first passed from the Caspian region through North then South Ossetia until it reaches the Black Sea. Last August, Russia took the opportunity of forcibly securing control for this route when it “liberated” South Ossetian territory from Georgia, i.e., from the control of the United States. But now a bigger obstacle to completing the pipeline has been put in Russia’s way: the economic crisis. Gazprom’s debts have suddenly magnified with the devaluation of the rouble and low energy prices which have reduced its revenue. Suddenly, it is faced with the difficulty of how to finance the $20bn project. Even so there is no talk yet of dropping it.

No mention either of whether this year’s planned launch of the St Petersburg bourse will be postponed or how much gas trade will be done in roubles now that the rouble has plummeted in value. (Despite Russia using up a substantial portion of the state’s currency reserves propping up the currency, the rouble has lost a third of its value over the past six months.) For the time being, the economic crisis has put paid to Russia’s ambition to break free of the dollar. However, that same crisis is not just weakening Russia. The battle for control of energy supplies and revenues is set to sharpen with the sharpening of the crisis. Policies based on Putin’s doctrine of “energy power” will be the shape of Russia to come.

Capitalist Profit Before People’s Needs

While Russia has been hammering home to Europe the need to break free of its dependence on routes through Ukraine the EU cannot have failed to be reminded of its reliance on Russian gas, or else gas from further afield coming via Russia. Indeed this may well have been a subtext of Putin’s message. On the one hand this encourages the EU to turn towards the idea of yet another pipeline which would circumvent Russia altogether and which, not surprisingly, is favoured by the USA - the so-called Nabucco project. This is designed to bring gas from central Asia and the Caspian area through Turkey by joining up with an existing fourth corridor, the joint US-EU financed Baku-Tiblisi-Ezerum route. The Nabucco project, backed by an Austrian, Hungarian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Turkish and German consortium, is even more costly than South Stream; it has its own strategic dangers (it would run through the Kurdish part of Turkey where the PKK has already attacked the equivalent oil pipeline); and it could not fully substitute for existing routes. At a conference about Nabucco - held just after the gas cut-offs last January and involving all the participant states plus the USA and the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) - Topolanek, Prime Minister of the Czech Republic and Gyurcsany, Hungarian PM, complained about the lack of interest in the project and argued that strategic interests should be put before financial ones. (8) However, as one of the EU’s energy spokesmen put it, “It (Nabucco) will be part of the solution but it will not be the solution.” (9)

In fact there is no secure energy solution for the EU although that will not stop it trying to find alternative supplies. The latest example of this is a plan by Total to join work on a trans-Saharan pipeline that aims to tap Nigeria’s gas reserves. However, Gazprom gets everywhere and it has already set up a subsidiary in Nigeria. At the same time as the EU is trying to diversify its supplies to become less dependent on Russia, Russia aims to broaden its market. At the moment, all of Russia’s existing gas export pipelines are directed into Europe. With a new project to supply LNG to Asia (North Korea and Japan) and North America from Sakhalin island in the Pacific, Europe’s position as the only foreign consumer of Russian gas will come to an end. On the supply side too, of course, Russia is intent on securing and extending its reach in Central Asia where the clash of imperialist interests has repercussions way beyond the price of gas.

Throughout the Cold War, the USSR did not once cut off the gas supply. Contrast this with today. For the EU, January’s gas crisis has only emphasised that Russia is ready to use energy as a political weapon. The era of blatant antagonism towards Russia without consequences has come to an end and rampant anti-Russian member states like Poland and the Czech Republic will have to be curbed. (Possibly aided by the new representatives of US interests in the White House.) On the gas front, Ukraine is in no position but to accept whatever Russia says and this will inevitably increase Russian influence. (Though the wrangling between pro-Western and pro-Russian factions amongst the ruling class is set to continue.)

For anyone with any sense the whole incident shows the absurdity of pretending that a world of capitalist states competing for profits can maintain the basic needs of its ‘citizens’, never mind implement a rational energy policy that would reduce carbon emissions and help save the planet. Far from that, the ‘unexpected consequences’ of an apparently local issue such as this ominously suggest how easily, at a time of serious economic crisis, a more dangerous imperialist conflict might occur.

E Rayner(1) Niall Trimble of the Energy Contract Company is quoted in The _Financial Times_ as saying, _“_We had the showdown between Russia and Ukraine, and some very cold weather, and yet the market did nothing”, 26th February 2009.

(2) Quoted in an article by Rafael Kandiyoti , “An Opec for Gas?” in Le Monde Diplomatique, English edition, February 2009.

(3) The internationally agreed price for gas is not really a market price in the sense of being determined by the cost of production and supply and demand. Instead the price is set in accordance with the manipulations of the OPEC oil cartel and speculation on the futures markets.

(4) According to an internet article by Vladimir Volkov, “The Russia-Ukraine Gas Conflict And The Geopolitical Struggle For Control Of Energy Resources”. 2nd 2 February 2009.

(5) Legally this ought not to be so easy. As The Financial Times reported before the gas crisis reached its height: “Ms Tymoshenko may be unable to squeeze Mr Firtash out of the trade altogether because Rosukrenergo holds separate rights to use Ukraine’s pipelines to export gas to the EU and orther Firtash companies have invested heavily in domestic Ukrainian distribution” (3rd December 2008). Now that Yushchenko has Russian backing the legal niceties will be less of a barrier. However, at the time of writing gas supply to Poland is still reduced.

(6) Volkov. op. cit.

(7) Kostis Geropoulos, “Gas Crisis Gives Fresh Impetus to Nord Stream, South Stream, Nabucco”, 12th January 2009, internet.

(8) “On the eve of the summit, Topolanek complained that the major member states of the EU, such as Germany, France Great Britain and Italy, were not showing the necessary interest in Nabucco since they have their own means of securing natural gas. Meanwhile the pipeline projects South Stream and North Stream, which are being built to obtain natural gas for Europe from Russia, represent a threat to Nabucco: the majority of the country-participants in Nabucco are simulataneously engaged in the Gazprom projects”, Volkov op. cit.

(9) Ferran Tarradellas Espuny, in an interview with New Europe, 7th January 2009.

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #49

Spring 2009 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.