You are here

Home ›British Capitalism and the Miners Strike of 1984-5

In February 1984 the miners in Cortonwood, South Yorkshire learned that their pit had been earmarked for closure. After a pithead meeting they voted for a wildcat strike on March 5th. They were soon to be followed by 6000 other miners. No-one at the time realised that this would lead to the biggest confrontation in the class war in Britain since the Second World War.

Many words have already been written in commemoration from different aspects. Many look on the struggle with a kind of despairing nostalgia, others on a world that has been lost, whilst others have simply focussed on the icons of the time.

For those who lived in pit villages the focus has been on the social devastation which followed, as pit after pit was closed down, and with it the only real employment in those areas. Today there are 6000 working underground instead of the 250,000 of 1984. In many villages youth unemployment rose to 70% well into the 1990s. The consequent social breakdown led to drug dealing and criminality on a hitherto unknown scale. By 1994 the Dearne Valley (which runs between Barnsley and Rotherham) was designated one of the three poorest areas in the entire European Union, and Grimethorpe the poorest village in Britain. The whole of South Yorkshire thus became an Objective 1 development zone.

Today a shopping centre stands where Cortonwood pit once was, and most of the other pithead sites in South Yorkshire, South Wales and elsewhere have been converted to mini-industrial estates offering low wage jobs to a few workers.

In other areas such as Nottinghamshire, where the miners did not strike, all but 3 pits have been shut (despite promises made that they would not) and here, they have not even bothered to “develop” pithead sites. But the impact of the strike went beyond the miners, and even beyond the shores of the UK, since the victory achieved by the British ruling class gave confidence to the rulers of other advanced capitalist countries to begin the process of restructuring of their economies in the face of the capitalist crisis. This was largely based on the de-industrialisation of the areas where the old heavy industries were located. In September 1984 we were still able to put this issue in more positive terms.

A victory for the miners will not only clear the way for a renewed offensive by the rest of the British workers who, up till now, have been cowed by unemployment and the catalogue of defeats over the past 5 years. It will also be crucial for the balance of class forces in Europe as a whole: the significance of the British miners strike overshadows all events in the class struggle in Europe since the Polish defeats of 1980-1. The embryonic revival in class struggle, as seen in the Belgian public sector general strike last year, and the struggle of the German metal workers this year, will be tipped towards upsurge or retreat by the outcomes of the present battles in the British coal industry.

Workers’ Voice 18, Sept 1984

Labour and the Capitalist Crisis

This turned out to be true and this article is an explanation not only of how that retreat came about but will also attempt to understand its significance for the future of the working class as a whole. The miners’ strike cannot be understood just by looking at 1984-5 alone. Its background was the capitalist crisis which engulfed the world in 1971-3 and which signalled that the post-war boom was over (or, as we would put it, the cycle of accumulation had entered its downward phase). The Heath Government at the time was portrayed as the most right wing Government since the war when it tried to tackle head on the chronic lack of productivity of British industry (due to a lack of investment, both before and after, the nationalisations of the 1940s). Their solution was simply to make the working class pay by cutting wages (via higher inflation and fewer jobs). It sparked a wave of militancy across all the nationalised industries but particularly in coal. In every case the workers won higher wage rises (even if soon undermined by the going rate for inflation).

In the 1972 strike Arthur Scargill led thousands of miners to blockade the Saltley coking depot and caught the police unawares. This victory of the flying picket was to inspire a similar tactic in 1984. The difference was that the state was ready and in the so-called Battle of Orgreave, for example, the coking works near Rotherham were protected by at least as many police as there were pickets.

However back in 1974 the miners not only succeeded in getting higher wages but even forced the Heath Government to call an election on the issue of “who runs the country”. The fact that the Tory Government of the day narrowly lost indicated a widespread class hostility to capitalist restructuring plans.

Unfortunately class hostility to capitalist restructuring was not the same as hostility to capitalism. At the time members of the CWO often voiced the view that “money militancy” was not in itself leading to any wider consciousness of the issues at stake as the working class gave more and more support to trades union struggles. As we know the unions have never been revolutionary and indeed their existence is bound up with capitalism. Asking for “a fair day’s pay” is not the same as demanding “the abolition of the wages system”.

In the pit areas this was stronger than anywhere though every mining community had its minority of socalled “communists”. But these were those who looked to the Stalinist Soviet Union as their model whilst most miners were content to go down the pit every working day past the sign which had announced since 1947 that this or that pit was “owned by the people”. For miners this was not only the culmination of a century or more of struggle but it also meant that you had a job for life. It seemed to give the assurance that you were taking part in a tough job but for the good of the community.

In fact it was a Labour lie. What they should have put above the pit was “owned by the nation” since this reveals that it was not owned by the workers but by those who had “the greatest stake” in the nation - those who really owned the land, the newspapers, the factories, mines and fisheries. The post-war nationalisation of “the commanding heights” of the British economy by a Labour Government is often portrayed as a step towards socialism, by all sides of the ruling class. It was in fact the exact opposite. The state became the collective capitalist in the interests of the bourgeoisie as a whole. The position of the workers was not altered by replacing individual capitalists with the state. The individual capitalists did not of course like it (though they got hefty compensations for their clapped out plant) but this was a ruling class in deep crisis. It had “won” a war which had destroyed its overseas markets (gobbled up by its American ally), three quarters of its merchant marine and was on the brink of losing the Empire which it had entered the war to defend. In this crisis the ruling class also had another weapon to deploy - the Labour Party, itself founded by the trades unions at the beginning of the century. By setting up the welfare state and nationalising loss-making industries the Labour Party conceded the demands of those who thought they had fought the war for “democracy”. But their nationalisations were not about “common ownership of the means of production” as the Durham miners in the 1950s and 1960s found out.

Nationalisation was but a prelude to rationalisation. Thousands of jobs were lost as Durham pit villages were turned into “category C or D” (which meant you had no hope left). The Labour Party’s service to British capitalism has never been in doubt from the moment they (and their union backers) supported the First World War in 1914 right down to the 1970s but the 1940s was “their finest hour” as they established a social state which saved capitalism from even more extreme demands from the workforce.

The Tories narrowly lost both elections in 1974 but the drive to restructure did not end there.

Obsessed by balancing the books in a way which looks almost laughable now, the Labour Government called in the IMF in 1976. Prime Minister Wilson, who once promised to use “the white heat of technology” to modernise Britain, resigned presumably because the IMF medicine was too hard to administer.

This brought Callaghan and Healey (as Chancellor of the Exchequer) to power and they carried out the cuts demanded by the IMF as a condition for its loans. The decline of the fight of the working class against the crisis began from that moment (and not from Thatcher’s arrival in power in 1979). The Labour Government not only used troops to break the fireman’s strike but made cuts in health and social security spending as well as imposing a “Social Contract” (widely dubbed the Social con trick) which tried to introduce a wage freeze at a time of high inflation. The “winter of discontent” (1978-9) it provoked spelled the end of Old Labour as a useful tool for the British ruling class and ushered in 18 years of Tory rule.

Background to the Strike

When the Tories arrived in power in June 1979 they had no master plan for solving the capitalist crisis but they had learned from the debacle of the Heath Government. They also had a plan to deal with the miners. This was the Ridley Plan (after Nicholas Ridley who would become a minister in Thatcher’s Government) which was no secret since The Economist announced it in May 1978. It summarised the essence of this plan thus;

...Mr Ridley and some of his coauthors have been pondering how to counter any “political threat” from those they regard as the enemies of the next Tory Government... they would like a five part strategy for countering this threat:

- Return on capital figures should be rigged so that an above-average wage claim can be paid to “vulnerable” industries.

- The eventual battle should be on a ground chosen by the Tories, in a field they think could be won (railways, British Leyland, the civil service or steel).

- Every precaution should be taken against a challenge in electricity or gas. Anyway, industries in those industries are likely to be required. The group believes that the most likely battleground will be the coal industry. They would like the Thatcher Government to a) build up maximum coal stocks, particularly at power stations; b) make contingency plans for import of coal; c) encourage the recruitment of non-union lorry drivers by haulage companies to move coal where necessary; d) introduce dual coal oil firing in power stations as soon as possible.

- The group believes that the greatest deterrent to any strike would be “to cut off the money supply to the strikers and make the union finance them”. But strikers in nationalised industries should not be treated differently from strikers in other industries.

- There should be a large mobile squad of police equipped and prepared to uphold the law against violent picketing. “Good non-union drivers” should be recruited to cross picket lines with police protection.”

In the end all of this came to pass but not quite according to the schema of Ridley and Co. Thatcher’s 1979 election victory was a narrow one.

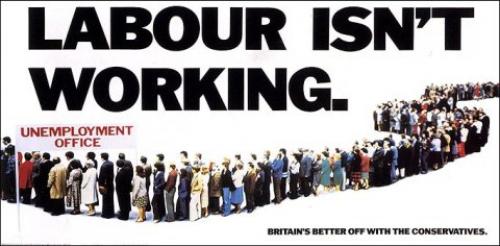

The Tories had won largely because the level of unemployment had tripled to 1.5 million under Labour (an issue made much of in Tory propaganda viz the “Labour isn’t working” posters of the Saatchi brothers reproduced on this page).

However under Thatcher this was to double again at a time when inflation peaked at 22%. The Thatcher Government became the most unpopular since Neville Chamberlain’s in 1940. However the Tory Government pressed on with socalled anti-trades union legislation which, by outlawing wildcat and solidarity strikes as well as mass picketing actually strengthened the hand of union leaders over the membership. In short the legislation was anti-working class and antistruggle than anti-union per se. Such legislation though gave the legal framework for what would happen in the miners’ strike. However the first clash was not with the miners but with the steelworkers who were initially offered a derisory 2% wage rise (i.e. a large wage cut since inflation was at 20% at that point) in the autumn of 1979. After negotiations only saw the offer raised to 6% (with job losses on top) the steel strike broke out in December 1979. For over thirteen weeks the steel workers struck and carried out many flying pickets to try to stop the movement of steel. In this they were supported by the miners who sent masses to reinforce pickets of private steelworks.. They were not so well supported by their own union (later the ISTC) led by Bill Sirs who did everything he could to get the strike ended on the bosses terms. When the deal was finally announced of a 16% wage rise, but only on condition that thousands of jobs would go, steelworkers in Sheffield publicly burned their union cards en masse.

The steelworkers defeat emboldened the Government. Ian Macgregor was brought in from the US to close much of the steel industry down and make it ready for privatisation (150,000 jobs in both the old British steel and private steelworks went over the next 20 years). And in 1981 the Thatcher Government thought it would take on the miners by announcing the closure of 23 pits. This provoked a spontaneous walkout of pit after pit starting in South Wales and then spreading across the country. The Tories were not yet ready to take on the miners so after a week of hesitation the shutdowns were shelved. This relatively easy victory for the miners was to induce a false sense of security that the miners could win on their own.

Things were also changing on the political front. The Thatcher Government’s unpopularity was at a historic low when a diplomatic failure was turned into military victory by the Falklands War. Encouraged by British apparent willingness to let them have the Falklands Islands the Argentine military junta of General Galtieri decided they could be seized without resistance. Galtieri’s regime, like Thatcher’s was in deep trouble economically and socially so this act of war was intended to divert national attention towards this great achievement. Lord Carrington, the British Foreign Secretary resigned over the diplomatic blunder, and there was some debate amongst the ruling class as to whether the Falklands were worth fighting for. But the Thatcher junta was desperate to copy Galtieri. Plans to scrap naval vessels were hastily abandoned and an expeditionary force was put together to recapture the islands. It was the political turning point of the 1980s. The “short victorious war” (1) against a weak enemy allowed the British ruling class to swell out their nationalist chests and to claim that Britain was once again a great player in the world. We wrote about the consequences as follows:

The failure of the working class to substantially oppose the Falklands War in 1982 led to a new wave of confidence in ruling class circles. This was reflected in the capitalist press. Until then the bourgeoisie had grave doubts about the open civil war tactics of the Tories. After the riots of the unemployed youth throughout Britain’s cities Thatcher was being described as the worst British Prime Minister since Neville Chamberlain . Today there has never been a better prepared offensive by the bourgeoisie than that being carried out by the present Conservative Government.

The Miners’ Strike and the Tasks of Communists in Revolutionary Perspectives 22, Third Series

The press played their part to the full. The Daily Mail (which had opposed giving asylum to “dirty” Jews in 1938) carried the headline “Smash ASLEF” as a rail strike began at the end of the Falklands War. All the papers pictured a returning troop ship with a banner hung over the side reading “Call off the rail strike or we’ll call an air strike”. A wave of jingoism not seen for decades swept Britain.

Much of the ruling class’ preparation was foreseen in the Ridley Plan but some went beyond even that. The police were militarised and centralised so that they could deploy large numbers to any area and the tactics learned in Northern Ireland were now part of their arsenal. Many of the coal fired power stations were modified to burn oil as well. The workers in the power generation industry and the police were both awarded large pay rises just before the strike broke out. As a result of oil huge stockpiles of coal built up at power stations and a work to rule by miners throughout the winter of 1983-4 to try to reduce it did not make significant inroads. And just to make sure the transport of coal was moved from the “unreliable” railways (since the railworkers would show class solidarity) to private coal firms staffed either by self-employed lorry drivers or non-union workers. Now the only provocation needed was to make Ian Macgregor who had “butchered” the steel industry head of British Coal.

As the ruling class prepared their position the situation had been moving against the miners in other ways. Once again attacks came from their supposed friends. The Minister for Energy in both Labour Governments had been Tony Benn.

He not only shut down 200 pits (with the connivance of the NUM leadership) between 1964-70 but in his second term of office in 1977 introduced a productivity scheme which offered big bonuses for miners in modern mines and nothing for those in older pits. The miners spotted this divisive game and rejected it in a national ballot. Joe (Later Lord) Gormley, the President of the NUM then implemented it area by area thus breaking the national unity of the miners. During the miners strike the miners went on strike area by area, and were roundly condemned in the capitalist press for not holding a national ballot but in 1977 no-one noticed this same “lack of democracy” when Gormley first introduced it. Neither did anyone remember Benn’s role as a Labour Minister when he shared platforms with Arthur Scargill during the miners’ strike! However the lack of a national ballot was a propaganda gift to the capitalist press. There is also no doubt that it helped undermine class solidarity since the fact that the Nottingham pits (foolishly believing promises that they would not be closed) not only stayed at work but produced a split in the miners’ ranks.

Union leaders also used it as propaganda to support their own capitalist interests. Bill Sirs (ISTC leader) rewarded the solidarity the miners had shown the steelworkers in 1979-80 by refusing any suggestion of solidarity with the words. “We are not going to sacrifice ourselves on someone else’s altar”.

The Great Strike

As it was the NUM leaders did not provoke the confrontation. It can even be argued that, as they had already negotiated the closure of half the 23 pits the Tories had wanted to shut in 1981, they were doing all they could to avoid a strike. In fact the spontaneous way in which the strike started and spread was not something the NUM leadership could control, and was more like that of the 1981 confrontation. Even before Cortonwood came out miners in Barony and Killoch pits in Scotland and Manvers and Wath in South Yorkshire had been on strike for three weeks. What made Cortonwood (and Bulcliffe Wood) different was that the miners there produced a leaflet which they took to other pits and then proposed a strike ballot in the Yorkshire area NUM. It was about this time that the disastrous slogan “Coal, not Dole “ was adopted.

It sounds clever but it posed the struggle as one for the miners alone when, as we wrote at the time, the miners were actually fighting for everyone. But “Coal not Dole” made it look as though this was simply a trade dispute and made it more difficult to get other workers to see the need for solidarity. In short it had the effect of isolating the miners from real solidarity (and we are not belittling the attempts of the various support groups to keep financing the miners to keep them going but the real solidarity that was required had to come from transport workers, dockers and other strategicallyplaced workers). However speaking to young miners during the strike we found that they thought that they could win on their own and had enormous confidence in the power of their union. Partly this stemmed from the structure of the NUM which was much more run by its members (as the Cortonwood initiative confirms) and less bureaucratic than any other union. But the NUM was still a union and the fact that this was seen as trades dispute and not for what it really was - the future of the working class in Britain, and beyond, played into the bosses hands.

In one of the many leaflets we gave out at the time we called for a generalisation of the struggle

No amount of militant fight by the miners alone will defeat the bosses, who have ranged the whole of the might of the capitalist state against the miners; they have spent more on defeating the miners, than in fighting the whole Falklands War, and turned whole regions of the country into mini-police states. The key to victory lies in the spread of the struggle to other sections of the working class. Instead of token support, the miners need more active help, like the kind briefly given by some dockers over moving scab coal to Ravenscraig, or the London printworkers who stopped production of The Sun for its attacks on the miners. But more important is for other workers to launch their own struggles, to open up other fronts in the fightback, and to link these fights with those of the miners, through joint picketing, demonstrations etc. Everywhere workers are facing the same problems as the miners; threats of redundancy, falling real wages, infernal increases in exploitation...

But the same leaflet went on to point to the role of the unions.

Any attempt to generalise and unite the struggles leads to conflict with the trades unions, which divide the workers section by section, and restrain any struggle within the bounds acceptable to capitalism. Thus the TUC has passed meaningless motions in support of the miners which are designed to leave them isolated. The ISTC has openly supported the use of policeescorted scab lorry convoys, and the EEPTU has indicated that it will call upon power workers “to work on” to defeat the miners. These were not “betrayals” as the Trotskyists at the time tried to maintain but the unions playing their real role for the capitalist state. The miners suffered the biggest onslaught in terms of state violence that we have ever seen since the General Strike of 1926. In the mini-police states we referred to above the police were restricting travel, carrying out arbitrary arrests of workers, beatings, photographing, finger printing, telephone tapping. At the same time the bosses have used their courts and laws to cut off money and food to striking miners. Strike funds have been seized and the strike declared illegal. Shipments of food from workers abroad have been turned back at ports or destroyed. Thousands of miners have received savage sentences on the flimsiest of charges. The entire bourgeois media, press and television have been united in a chorus of hatred and lies against the miners in the name of democracy and freedom. In fact so-called “democratic freedoms” have been wiped out and the present society revealed for what it is, the dictatorship of the capitalist class over the workers.

Break the Miners’ Isolation in Workers Voice 85, January 1985

There are many, many, aspects we could go into and many already have.

We could highlight how the so-called battle of Orgreave in the summer of 1984 was one of the biggest diversions from the real picketing of the power stations and steelworks at a time when the ruling class was itself beginning to doubt the wisdom of fighting on. We could show how the miners passed from passive picketing towards real class violence when faced with an obdurate and violent enemy. The defeat was not inevitable and there were times when the Tory Government’s nerve was shaken (naturally when the pound and the stock market tumbled). We could also point to the incredible sense of community which the strike revealed. The Tories thought that by getting a lot of workers to buy their council houses they would trap them in the so-called “property-owning democracy” where paying the mortgage outweighs any tendency to militancy. It may have worked elsewhere but in mining villages the building societies did not dare foreclose on mortgage arrears whilst the strike was on. This apparently made Thatcher incandescent with rage as she had already pronounced that there was “no such thing as society”. She certainly destroyed the mining communities in pursuit of that piece of dogma.

The Lessons

But what the miners strike really showed was that militancy alone is not enough to win a battle on this scale. For the British bourgeoisie restructuring the old state- owned industries was absolutely vital but to achieve it they had to impose the most draconian of cuts on the bulk of the working class. The issue was never about modernising Britain - it was always about exploitation. And the evidence of their victory is all too apparent. Today families are more likely to exist on two low paid jobs (where they have them) rather than on one wage which can support all.

Real wage rates have fallen continuously since 1973 whilst the ruling class have transferred industrial production to areas across the globe where they can exploit workers on minimal wages. They have been able to use the profits to indulge in the financial speculation which artificially gave the idea that real growth in the economy has taken place over the last two decades. At the same time they have tried to reduce the working class in Britain and all the advanced capitalist countries to the status of plebians, given enough bread (social security) and circuses to maintain them as consumers of the commodities produced by the quasi-slave labour of the “emerging nations”. The speculative bubble has now ended in tears and once again as in the 1970s and 1980s the working class will be asked to pay for it. Where we go from here depends on the response of the working class everywhere. So far we have seen violent resistance in China and Korea and workers occupying factories and kidnapping managers in the advanced countries.

However these are as yet not the stuff of a generalised class movement.

The miners’ strike proved for all time that our collective resistance is not just economic and social but has also to be political. We can put it whichever way round you like. There was not enough consciousness so there was no workers’ party or there was no workers’ party so there was insufficient awareness of the stakes to play for. At the time of the miners’ strike the workers were not really conscious that what they were fighting for was a bigger stake than just the survival of one industry.

They had little realisation that they themselves would have to forge a new society. And this is why there was no political party of the working class which had an alternative vision of the society we need. Politically the capitalists understood what was at stake in 1984-5 and this is what we have to understand now. Whilst our daily resistance to exploitation is the basis for the future of the unity of workers actions it won’t be through a spontaneous outburst here or there alone that we will achieve the understanding that we need a programme which envisages a different kind of society.

It is likely that the current crisis will be managed by the state so that we are in for a gradual worsening of living conditions world wide. In this period communists need to explain that the only future this system has to offer is one of permanent wars, declining living standards for the majority and environmental degradation to the point where the existence of humanity is threatened.

This means we have to help develop the consciousness of the working class to an awareness that it alone, as the one collectively exploited producing class, has the capacity to solve humanity’s problems. This means going beyond struggles in this or that workplace, and to raise our sights for the struggle for a society based on human needs and not capitalist profits. We can still do it - but only if we learn the lessons of our own history.

Jock(1) The phrase is from the Russian Interior Minister Plehve who suggested to the Tsar of Russia in 1904 when faced with mass strikes that what he needed was a “short victorious war” to play the nationalist card. Unfortunately for “Nicholas the Bloody” Russia chose to fight a newly emerging Japan and lost thus provoking the 1905 War. The British Government had no such problems when faced with the decrepit dictatorship in Argentina (which was duly overthrown after the war).

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #51

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.