You are here

Home ›Capitalism's Economic Foundations (Part VI)

You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows

Bob Dylan, Subterranean Homesick Blues, 1965

Our analysis of capitalism’s underlying driving force which gives rise to periodic economic crises (the falling rate of profit and capital’s efforts to offset it) has brought us to the contemporary world and it’s now time for us to draw this study to a close. In the real world, of course, there is no closure. If there was some doubt amongst revolutionaries about capitalism’s inbuilt tendency to crises and, in the era of global capitalism, to devaluation of capital through a world war, there is much less scepticism about this today, for obvious reasons. We are about to wind up this economic overview as an increasing number of states appear to be rapidly moving, from primarily economic rivalry to military rivalry, with the prospect of a third world war being openly talked about. It is important that revolutionaries have at least a basic understanding of the economic crisis that is driving capitalism towards potential catastrophe in order to recognise that there really is only one alternative: war or revolution, for which we have to try to prepare the working class. Yet it is hardly enough, and less than convincing, to depict (or predict) present-day economic and political trends as simply heralding a repeat of the run to the Second World War, or even the First, with only a change of major dramatis personae. This series itself (based on what we originally wrote in 1975) is testimony to the unprecedentedly long, drawn-out nature of the world crisis which dawned in the early 1970s and eventually led to the globalised capitalism we know today. Half a century on, as globalisation appears to be on the brink of retreat, as the space for financial engineering is perceptibly narrowing, and as spending on ‘defence’ budgets rise while cuts are made elsewhere, it is essential to examine the way the wind is blowing for capitalism more carefully.

Traditionally capitalism’s cyclical crisis was marked by a growing number of firms going bust (bankrupt) in the face of declining profitability which made it no longer worthwhile investing (i.e. no longer profitable, the fundamental raison d’etre of capitalism). After a period of write-offs and takeovers of bankrupt firms a new round of capital accumulation could take place, albeit at a generally lower rate of profit than previously for the now-larger firms ready to supplant traditional domestic handicrafts and encompassing a wider geographical area. Eventually this process, though hardly a period for outright celebration by the growing class of wage workers whose unpaid labour was the basis of capitalist society’s burgeoning though inequitable material wealth, created the social and material potential for a new world order. Collectively the working class had created the basis for a stateless (because classless) world of material plenty which, once freed from its inequitable capitalist frame with its inbuilt cyclical crises, could lay the basis for the peaceable existence of the whole of humanity. However, the concrete realisation of this potential demands more than establishment of the economic conditions. It demands the revolutionary will, political consciousness and organisation of the international working class: essential elements which do not spring altogether ‘naturally’ from the material situation and are outside the frame of this article, though not of course, from our wider concerns. Suffice it to say here that, without political revolution, decaying global capitalism will continue its infernal cycle whereby war serves to devalue capital, possibly destroying the bulk of humanity in the process.

Keynes thought he had found the answer to this cycle with state management via deficit financing to prevent bankruptcies in key industries. Governments became adept at conjuring up ways to spend more than their income via taxation in order to support ‘the economy’, either directly or indirectly via tax breaks and so on, to avoid mass unemployment and industrial recession. By the 1970s, however, the fall in the rate of profit made this strategy increasingly costly and ineffective. Ironically, the clearest example of deficit financing is something Keynesians generally abhor: spending on war, where governments resort to the printing press and the yardstick of profitability makes way for a whole economy geared to the ‘waste’ of war production. The destruction of capital values in war does, however, lay the basis for a recovery of the rate of profit, thereby providing the basis for economic reconstruction ... assuming, that is, there is something left to reconstruct after the next war.

In fact the advanced economies, from which the crisis re-emerged in the 1970s, were already supported by deficit spending. As the crisis wore on, concerns over mounting levels of government debt were a major factor in the adoption of the monetarist policies advocated by the likes of Milton Friedman. Far more significant, however, in terms of the evolution of the crisis, are the myriad steps that have been taken to ease financial speculation.

Interest bearing capital is always the mother of every insane form, so that debts, for example, can appear as commodities in the mind of the banker(1)

Marx

‘De-regulation’ of banking, famously begun by Reagan in the United States and Thatcher in Britain, turned an ever-increasing share of ‘profit realisation’ simply into returns from gambling via financial speculation, without the inconvenient and unnecessary worry of calculating the cost of machinery/raw materials/wages in the estimation of the likelihood of monetary profit or loss. In the process, ‘ordinary people’, i.e. the working class, were also drawn into the whole dodgy business of financial speculation. Enticed to put their savings into high interest rate/high risk bank accounts and extend their mortgage borrowing, wage workers were even encouraged to engage directly in stock market speculation, notably, but not only, via the company shares employees of de-nationalised industries were allocated on privatisation. Of course financial gain in itself does not indicate the creation of new value since speculation is hazarding a bet on already existing values. One speculator’s gain is another’s loss unless, however, fresh money flows into the system via quantitative easing or other state created schemes. In the longer term this in effect resembles a vast Ponzi scheme which is likely to collapse as it did in 2008. The real problem is a growing shortage of surplus value to reinvest in productive industry. However, so long as the nominal worth (the buying power) of the currency in which speculation is occurring (usually the dollar, but also other major currencies, viz the euro and pound sterling) holds up, the winners from financial ‘risk taking’ are generally happy enough regardless of the focus of their investments. (For the financier the target for financial speculation in itself is of no matter: tar sands or wind farms, drones or a wonder drug to combat Alzheimer’s or future prices of oil, future interest rates, sub-prime property or whatever else they can think of … the key factor to consider is the rate of return on capital outlay).

Still, since de-regulation, regular financial crashes have plagued the world economy: 1990, 2001, 2008 and 2020 (coinciding with the Covid crisis and state measures to offset its economic impact, including trillions of US dollars and Chinese deficit financing on vast Keynesian-style building projects). William White, former economic adviser at the Bank for International Settlements, has pointed out that each crisis had its origins in monetary stimulus intended to foster recovery from the previous recession but each one ended in financial bust and a new recession.(2) Moreover, the very low interest rates adopted after the 2007-09 financial crisis encouraged a huge rise in borrowing.

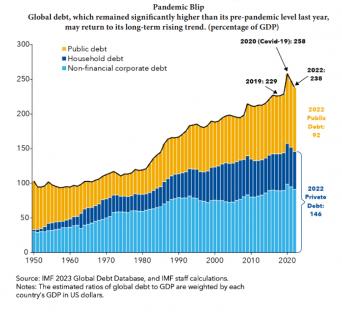

The trend of global debt up to 2022 is shown by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) graph below. Today, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), global debt is even higher than the IMF calculates. The IIF calculates, global debt rose from 280% of GDP in 2008 to nearly 360% in 2021 as a ratio of GDP. At the same time the IIF also noted that this increase coincided with diminishing productivity growth (dare we suppose that this is due to the high organic composition of capital?) and declining prospect for GDP growth across major economies as ‘the search for yield’ has driven European and Japanese savings into US assets.

As one Financial Times commentator, John Plender, succinctly puts it: "We are now left with an intractable debt problem that acts as a drag on consumption and investment, and the world is at risk of severe financial instability whenever central banks raise rates.”(3)

Previously seen as a solution by the economic pundits, borrowing and financial speculation are now regarded as the problem. The debts have interest attached to them which is the cause of the drag Plender speaks about and is often significant. The interest of the US sovereign debt, for example, was $875bn in 2023 which is now more than the vast US military budget. The debt itself is now $35.4 trillion. For the most part this interest simply results in the creation of even more debt. Printing money (or rather, allocating nominal amounts of currency to relieve debt), however, can only be done by countries who have debt in their own currencies, a possibility not open to most countries which have borrowed in dollar loans organised by the IMF or World Bank. Instead the interest will go into further speculation. All this can only inflate further financial bubbles leading to further explosions like that of 2008. In the world of finance capital, however, this neither means the end of speculation, nor of competition amongst the biggest players on the global and financial markets over ‘management’ of funds from all over the world (who thereby get their own financial rake-off). Needless to say, the UK as well as the EU is losing ground to the United States with the nominal value of “assets under management by US groups” increasing from $2.1 trillion in 2014 to $4.5tn by September 2024.(4) Last year was particularly bad for the London Stock Exchange which saw its biggest outflow of listed companies (88, with only 18 replacements) since the 2007/8 financial crisis. Now, London is even losing out to stock markets in India and Dubai, something which is making Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, consider encouraging the UK’s “vast sprawling” pension funds to invest in “higher risk equity assets”— hardly a reassuring thought for the workers who will depend on some of the proceeds of those funds in their retirement.

While sterling loses what little remains of its old imperial standing in financial markets, the US dollar apparently reigns supreme with the US stock market recently described by the Financial Times as “a global behemoth, comprising 75% of the MSCI world index at the end of 2023”.(5)

Nonetheless, stock markets are not the be all and end all of world domination, especially in this uncertain world where recent financial crashes have wiped out billions of dollars’ worth of share values. More fundamentally, the US, once the post-war world’s economic super-power, has been losing ground in regard to the rest of the world ever since the 1960s when its share of global GDP peaked at 40%. Today that share stands around 26% and, according to some measures, China’s share is now higher.(6)

In this context the dominant position of the US dollar, like sterling before the Second World War, is inevitably being challenged. Given US-imposed trade sanctions as a consequence of the war in Ukraine, the challenge is even more urgent for Russia. China and Russia have almost completely phased out the dollar from their bilateral trade which reached a record high of over $200 billion in 2023 or 2024 (depending on the source). Russia has also begun replacing its dollar reserves with yuans and euros. Between 2013 and 2020, the Russian central bank halved its dollar-denominated reserves.

In the wider world too there is undoubtedly a growing urge to get out of the grip of the dollar. Last October the IMF and World Bank convened for their annual meeting in Washington, marking the 80th anniversary of their creation and the post-war order they had helped establish. Significantly for the outlook of this order, the thirty-six BRICS countries, led by China, Russia, India, Brazil and South Africa, with Egypt, Iran, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates joining for the first time, were meeting separately for their annual summit in Kazan, Russia. Under discussion, naturally, was the question of how to establish a new international payments framework to circumvent the US dollar-dominated system. Significantly too, beyond the immediate concern of the summit, Xi Jinping announced a new era of “turbulence and transformation” whilst suggesting to Narendra Modi, that as leaders of the world’s two most populous countries, they should promote the “multipolarisation of the world and the democratisation of international relations”. (That’s rich given the wariness and constant border skirmishes between the two states.) Typically too, Turkey’s president Erdoğan chose to attend, despite being leader of a NATO member state never mind candidate for EU membership, whilst Egypt and the UAE are also western military allies.

This open challenge to the US-controlled post-war order was made even more clear a few weeks later by Putin, two days after Trump’s election. In his opening address to an annual conference in Sochi entitled, “Lasting Peace on What Basis?”, Putin drew a historical parallel to the Russian Revolution of 1917, reminding the audience how past revolutions reshaped societal and political frameworks worldwide. Similarly, today:

Before our eyes an entirely new world is emerging … and what is at stake is the West’s monopoly which emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union.(7)

This is at the source of soon-to-be-inaugurated President of the USA, Donald Trump’s recent warning to BRICS’ economies on the dollar.

We require a commitment from these countries that they will neither create a new BRICS currency, nor back any other currency to replace the mighty U.S. Dollar or, they will face 100% Tariffs, and should expect to say goodbye to selling into the wonderful U.S. Economy.(8)

Although the dollar is increasingly avoided by BRICS members in direct trade with each other, so far they have failed to create a credible alternative for wider global trade. Significantly though, last June Saudi Arabia did not renew its 50 year old agreement to trade its oil only in dollars. This is a major blow to the dollar’s dominant role in world trade and, as Trump’s rantings suggest, a further step towards all-out trade wars.

Which brings us back to tariffs and trade wars and the apparent similarity with the world following the Wall St crash prior to the Second World War.

Here, we must be careful. Even if capitalism is fundamentally subject to economic cycles, history is not a revolving circle with only the identity of the participants changing. As Engels explained in regard to the evolution of capitalist competition in the late nineteenth century,

most of the former breeding grounds of crises and occasions for crisis formation have been abolished or severely weakened. Competition in the home market is also retreating in the face of the cartels and trusts, while on the foreign market it is restricted by the customs tariffs with which all major industrial countries except England surround themselves. But those tariffs themselves are nothing less than the weapons for the final general industrial campaign to decide supremacy on the world market. And so each of the elements that counteracts a repetition of the old crises, conceals within it the nucleus of a far more violent future crisis.(9)

In other words, we should not expect a straightforward repeat of the run-up to the Second World War with simply a change of dramatis personae.

This is not to deny that the world is in a very dangerous place today. As Engels recognised, the very measures being taken by capital to avoid a repetition of the previous world crisis have ensured that the next crisis will be even more damaging and extensive. Today the tail-end of capitalism’s cyclical crisis involves dangers which extend far beyond strictly economic grounds, notably the potentially cataclysmic effects of climate change. The prospect of capital seriously turning its technological ability and scientific know-how to the task of combatting this is diminishing with the rate of profit.

Meanwhile globalisation has left the world with a complicated web of supply chains which, if they are to be rejigged, means a dearth of raw materials and technological/industrial infrastructure in some key places which, if not impossible to redress, will take time for reshaped power blocs to reorganise.

Reshaping Global Trade

In fact, however, the global expansion of free trade had already begun to wane when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. By 2011, after years of negotiations, the WTO’s Doha Round failed to agree on lower agricultural and textile subsidies. Between 2016 and 2020 the United States and China imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of each other’s imports. Trump has already announced that his new administration will place tariffs at the forefront of negotiations on a wide range of issues starting in 2025. However, it is not only Trump and the Republicans who are working against the logic of the free market. Biden’s blatant state support measures via the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 which allocated $400bn in tax incentives, loans, and grants is essentially a programme of state subsidies. No matter that about 40% of them were delayed or put on hold, the point is that the stronghold of the free market is resorting to state subsidisation of industry, and not just the arms industry. More directly Biden, like Trump before him in the White House, had no compunction about slapping on tariffs. Moreover, in May 2024, just over a year since US Treasury secretary, Janet Yellen publicly stated that Washington was not trying to decouple from China, and that a “full separation” of the economies would be “disastrous” for both countries, Biden sharply raised tariffs on imports of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean energy products and said he would keep all of Trump’s previous China tariffs. Unsurprisingly Beijing accused Biden of reneging on Yellen’s pledge. Hypocrisy of politicians aside, it is evident that whoever is in the White House the United States will be protecting its own immediate economic interests. What is significant is that free trade is viewed as not in the interests of the US manufacturing industry, not just the old rust belt kind, but contemporary items such as solar panels, batteries and EVs which cannot be produced as cheaply as in China. For US consumers the effect will be to raise the price of EVs, solar panels and so on, while China, ceteris paribus, continues to sell its cheaper products to the rest of the world. Eventually, that is. As one Financial Times journalist ironically notes, “Almost two years after the IRA was passed, the US has only installed seven new EV charging stations covering a total of 38 spots for drivers. This would be insufficient to cover a suburb in Luxembourg.”(10)

In the wider world too trade barriers are increasing. While the European Union is itself testimony to the existence of trade walls and tariff barriers, we hardly need to mention the obstacles and increased costs for post-Brexit trade between the UK and the EU, nor the embargoes on Russian exports in the wake of the war against Ukraine (embargoes that are deliberately circumvented and a blind eye turned when it comes to critical grain supplies from the world’s biggest exporter to places like Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Algeria.)

At this point it is worth noting that in historical terms, that is by contrast with the 1930s, the various trade barriers being erected today in the world are miniscule and often no obstacle to closer internationalisation. In 1981, for example, the US imposed a ‘voluntary restraint agreement’ limiting Japanese car exports to the US to 1.68 million per year. One of the consequences of this was that Japanese firms began assembling cars in the US and entering into partnerships with American car companies to get around the export restrictions.

By contrast, after the Wall St stock market crash in 1929, the United States increased almost 900 tariffs by 20%, sparking tit-for-tat retaliation from other countries in the form of more tariffs. As a result, global trade contracted by two-thirds within five years and although Roosevelt somewhat reduced US tariffs the trade walls were well up and the road to world war clearly defined. The average tariff rate today is 2.5%, down from 3.6% in 1993.

That said, the mutual trade barriers between the United States and China are much higher than the average, and getting higher. Biden’s so-called “small yard, high fence” approach introduced in 2021, which was supposed to restrict exports to China of technological equipment “related to national security”, quickly expanded to include just about any equipment and ‘virtual services’ that can conceivably be used for military as well as civilian purposes.

By May 2024 the Biden administration was still arguing that they were pursuing a policy of “de-risking” over national security items, not decoupling from China, when import tariffs on Chinese EVs and other clean energy products, including batteries, were sharply raised. (For example the tariff on Chinese semiconductors was doubled to 50%.) No matter whether there was an element of pandering to the ‘blue collar’ vote here, the fact is the measures were taken and were not the last to be implemented by Biden. Moreover, despite all the criticisms he had had of Trump’s tariffs on $300bn worth of Chinese goods, they remained in force under Biden’s presidency.(11)

The New Year opened with the tail-end of yet more restrictive measures of the Biden regime coming into force. US investors in Chinese venture capital funds are racing to comply with new rules banning them from backing companies that develop artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies used by the People’s Liberation Army.

As one person in the know about investing in China, an executive at an American endowment fund, put it:

US dollar foundations are done committing to China, period…The hurdle for making new commitments on the private side is 50,000ft high(12)

If the Biden administration last year could still pretend that raising the height of the US trade wall with China was a strategic and political tweak to protect military and national security, this only confirms that the game is really a much wider one, about ‘de-coupling’ of the two economies. This, despite the ties that yet bind together certain elements of the two economies.

Meanwhile, although China is being careful to avoid blatant transgressing of US ‘sanctions,’ its ties with Russia after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have accelerated. And not just China; other countries are also still trading with Russia. India buys Russian oil, the UAE enables financial transactions, and Kazakhstan, Belarus and Turkey provide hubs for Russia’s parallel imports — goods shipped through third countries outside the US trade embargo. But China is the most important, not only until recently ramping up exports to its neighbour but also buying Russian oil. Russia last year surpassed Saudi Arabia to become China’s biggest supplier of oil.

In 2023, 60% of Russia’s imports of dual-use high technology goods, as defined by the EU’s trade regulations, came from China, according to a Financial Times analysis of Russian trade data.

More generally too, China’s economic clout continues to mount. As the same perceptive piece in the Financial Times noted:

The world’s second-largest economy claims to be the biggest trading partner of 120 countries, doing business with most nations regardless of their politics. This gives it a growing role as an economic enabler of a large range of countries, including those antagonistic to the US-led west, such as Russia, Belarus, Iran, North Korea and Venezuela.(13)

The gloves are off and it’s not just about trade and being the world’s biggest exporter. China is bent on challenging US imperialism and the ‘rules based order’ it gave itself after the Second World War just as much as the US is determined to hold onto, and fight to retain, its own supremacy. From the South China Sea, through the Indian Ocean to a burgeoning list of interventions in Africa,(14) China is demonstrating its long-held military/strategic ambitions. Meanwhile in the USA global defence companies are recruiting workers at the fastest rate since the end of the Cold War. There is now a scramble amongst the world powers for once little-known metals and rare earths that are crucial for up to the minute technology, including on the military front — the importance of which China has long been aware. China produces about 60% of rare earth elements, and processes close to 90%. Now the US and the rest of the world are running to catch up.

There is no happy ending under capitalism. Global capitalism’s inbuilt tendency to self-destruction has brought us to an all-too familiar place. The best hope, the only hope for humanity, remains the one force whose interest it is to see an end to all factions of capitalism: the global working class, the fruits of whose labour power have been stolen by the capitalists ever since the days of the power loom and the spinning jenny.

ERCommunist Workers’ Organisation

Notes:

(1) Capital Vol 3, Ch 27 p.596 (Penguin 1992), ‘The Role of Credit in Capitalist Production’

(2) John Plender, Central banks need escape route from boom bust cycle, Financial Times, 1.11.24

(3) ibid.

(4) Harriet Agnew and Brooke Masters, 'The relentless advance of American asset managers in Europe', Financial Times, 17.12.24

(5) Philip Coggan, 'The zero-sum game investors are betting on', Financial Times, 28.12.24. The MSCI referred to here is a global stock market index that tracks the performance of around 1,500 large and mid-cap companies across 23 developed countries. It is maintained by MSCI, formerly Morgan Stanley Capital International.

(6) According to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook’s ranking of GDP according to purchasing power parity, China’s GDP is the world’s highest at $35.29 trillion while the US stands 2nd, with $28.8 trillion.

(7) Quote from Financial Times piece by Gideon Rachman, 'The birth of a new world order', 28.12.24; plus information fromValdai Discussion Club website: valdaiclub.com

(8) Variously reported, see for example, 'Trump threatens 100% tariff on Brics nations if they try to replace dollar', 1.12.24: bbc.com

(9) Engels’ note in Capital Vol 3 p.620

(10) Edward Luce, 'America is pulling up the drawbridge', Financial Times, 15.5.24

(11) Demetri Sevastopulo, ‘Are the US and Chinese economies really about to start ‘decoupling’?’, Financial Times, 19.5.24

(12) Tabby Kinder and George Hammond, 'US investors in China venture funds race to comply with new tech rules', Financial Times, 1.1.25

(13) Joe Leahy, Kai Waluszewski and Max Seddon, ‘China-Russia: an economic ‘friendship’ that could rattle the world’, Financial Times, 15.5.24

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #25

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.