You are here

Home ›Centre of steelmaking shifts to Asia

We are publishing below a discussion text on the Tata takeover of Corus. The text deals with some of the consequences of globalisation and its implications for imperialism and the working class. The conclusions both explicit and implicit are the subject of discussion in the CWO. More will be published on this issue in future editions of RP.

Tata Takes over Corus

In February the Indian steelmaker “Tata” took over the Anglo Dutch steelmaker Corus, paying £6.7bn for the company. This takeover represents a further consolidation of the global steel industry and continues the trend set in 2006 by Mittal Steel’s takeover of the European steel giant Arcelor. It also illustrates the gradual shift of the main centres of steelmaking and control of the industry from Europe and the US to Asia. However, in addition, this takeover also represents a significant export of capital from a country on capitalism’s periphery to countries at its centre.

Global consolidation of steelmaking

Tata’s takeover of Corus is the latest step in a long process of concentration and rationalisation of the steel industry which has been underway since the 1960s. As with other major industries this process has been driven by the struggle of the capitalist class against declining profitability. There has been a constant need to restructure the older sections of the industry and introduce new plant and working conditions to achieve the average global profitability levels set by the newer producers. In addition to this, steel production has also been considered a strategic national industry which needed state protection, because, without a national steel industry, it would be difficult to project imperialist power and impossible to fight significant wars. The vital role played by steelmaking in industrial economies is shown by the fact that it has previously been considered as an index of economic power and economic progress.

The creation of Corus and also Arcelor represented restructuring of the steel industry on a pan European level. Corus was formed from an amalgamation of British Steel and the Dutch steelmaker Koninklijke Hoogovens in 1999, while Arcelor was formed from a merger of 3 European steelmakers in 2001. The latest takeovers will increase the scale of operations enormously. Mittal/Arcelor is now the largest steelmaker in all markets, apart from Asia, and Tata/Corus is now the 6th largest global producer. Restructuring and rationalisation on a global scale can be expected. Tata, for example, has promised £350m of savings from reorganisation, low cost steel from India, cheaper Indian marketing and shipping. This consolidation is only the latest step in a long process of restructuring which, at each stage has entailed plant closures and massive reductions in the workforce. The scale of this process can be appreciated by briefly examining the history of British Steel.

The British Steel Corporation (BSC) was created in 1967 by the nationalisation of the 14 main steelmaking companies in Britain which together constituted 90% of the steelmaking in the country. At this time steelmaking was considered strategically vital and a 10 year development strategy was drawn up. This entailed closure or many plants, concentration of steelmaking in 5 main areas (1) and a £3bn investment plan under which new plant would be installed. At the time of nationalisation there were 268 500 workers in the steel industry. The economic crisis of the 70s meant BSC again started to lose money and this brought a programme of massive plant closures. These started in 1975 under the Labour government. However, these closures were not sufficient, and in 1980 BSC was still losing £300 million annually. The new Conservative government provoked a strike by demanding speed ups and offering a 2% wage rise at a time of 16% inflation. The strike, which was the first steelworkers had conducted since the 1926 general strike, lasted 13 weeks. It was, however, defeated and this defeat opened the path for more swingeing plant closures and redundancies. By the end of 1980 the workforce had been cut to 130 000, which meant that half of all the jobs which existed in 1967 had been axed. By the mid 80s BSC was able to boast that there had been a threefold improvement in productivity since 1980 and a tonne of steel was produced by only 4.7 man hours of labour. (2)

By the end of the 80s BSC was once again profitable. (3)

This was the prelude to privatisation which was carried out in 1988. The new company, now called British Steel, was heavily dependent on the demand in the British economy and did not generate profits until the economic upturn at the end of the 90s. Its weakness precipitated the merger with Koninklijke Hoogovens to form Corus. Today Corus has only 41 000 workers, 25 000 of whom work in the UK. This means that in the 4 decades since 1967 the workforce has been cut over 90%.

Capital flows

Tata’s acquisition of Corus represents a significant flow of capital from India to the EU. It is not the only example of Foreign Direct Investment coming from capitalism’s peripheral countries to the central countries. For example, Korean electronic companies have invested $2.5bn in electronics factories in the UK; Korean Car manufacturers are setting up plants in the Czech Republic and Slovakia; Mexican concrete manufacturers have taken over part of the concrete industry in the UK investing $5.8bn in it, while Chinese car manufacturers bought up UK’s Rover car plant. Nanjing Automobile Corporation (NAC) is reopening the Rover car factory in Birmingham and plans to produce 50 000 cars in the UK within 2 years. While these capital flows to the central countries are relatively small, worldwide the export of capital from peripheral countries is increasing.

| Group receiving FDI | FDI $bn | % Total |

|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | 542 | 59 |

| To developing countries | 334 | 36 |

| S/E Europe & CIS (ex Soviet Union) | 37 | 4 |

| Total inflow of FDI | 916 | - |

.

| Country | FDI $bn | % Total |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 165 | 18 |

| US | 100 | 11 |

| China | 72 | 8 |

| EU | 422 | 46 |

.

| Group/Country | FDI $bn | % Total |

|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | 647 | 83 |

| Developing countries | 133 | 17 |

| China | 33 | 4 |

| Total FDI provided (+) | 779 | - |

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (4) which monitors worldwide Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) reported that in 2005 $133bn, or 17% of global FDI, originated in developing countries. Some of the conclusions of the report are shown in Table 1 above.

These figures are provided by bourgeois economists and do not directly show movements of new capital invested. Tata’s takeover of Corus was a Merger and Acquisition (M&A). This type of operation only changes the ownership of the capital and does not represent a flow of investment capital. Flows of investment capital are lumped together with operations such as M&As and even capital reorganisation within multi nationals. Such accounting can produce anomalies such as the reporting of the UK as the largest recipient of FDI. (5)

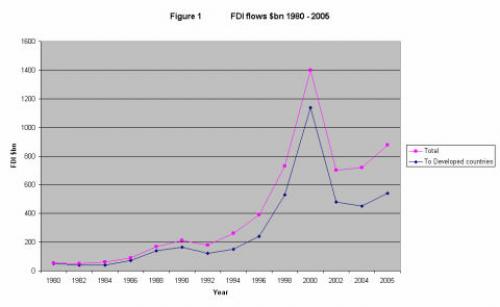

UNCTAD reports that 78% of the capital movements they record are M&As, which means that less than 22% are movements of capital for new investment. However, despite these reservations the figures do indicate trends in global capitalism. It can be seen from Table 1, for example, that in 2005, 59% of all FDI went to the central, or in UNCTAD’s terminology developed, countries, whereas only 36% went to peripheral, or developing countries. These figures are, however, massively changed from the 80s as can be seen from Figure 1.

In 1980, 96% of all FDI went to the central capitalist countries with only 4% going to peripheral countries. By 1990 the ratio had shifted to approximately 80% to the central and 20% to the peripheral, and today it is 59% to 36%. The other trend illustrated by Figure 1 is the massive increase in FDI during the last 25 years. In 1980 only about $50bn of FDI was recorded whereas in 2005 it had become $ 916 bn; which means it has increased by a factor of 17. The increase in FDI points to the changes which globalisation of production is bringing about. One of these is the shift in economic power towards Asia and the rise of China and India as industrial powers.

According to the International Steel Statistics Bureau (ISSB) (6), China is now the world’s largest producer and exporter of steel and accounts for 34% of the world’s steel production with the USA now only accounting for 8%. The production of the world’s main steelmakers is shown in Table 2. (7)

| - | Million metric tonnes | % Change | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 China | 418.8 | +18% | 34 |

| 2 EU25 (+) | 198.7 | +6% | 16 |

| 3 Japan | 116.2 | +3% | 9 |

| 4 USA | 98.6 | +6% | 8 |

| 5 Russia | 70.6 | +7% | 6 |

| 6 South Korea | 48.4 | +1% | 4 |

| 7 India | 44.0 | +8% | 3.5 |

| 8 Ukraine | 40.8 | +6% | 3 |

| 9 Brazil | 30.9 | -2% | 2.5 |

| 10 Turkey | 23.3 | +11% | 2 |

The Chinese economy is now larger than the UK economy and the Indian economy is expected to overtake the UK’s by 2016. Goldman Sachs, the US investment banker, predicts, from its model of the global capitalist economy, that the Chinese and Indian economies will be larger than the US economy in the 2030’s and 2040’s respectively. Seismic shifts of economic power are taking place. The question is whether the present framework of imperialist relationships will allow such shifts to occur without opposing them militarily.

New imperialist rivalry and war lie ahead

While the centre of gravity of industrial production is shifting to the countries on the periphery of capital, the majority of the capital remains in the hands of the central countries. According to the UNCTAD report there is a total $10 770bn of capital invested abroad worldwide. The central capitalist countries, predominantly US, EU, Japan, own 87% of this, while the peripheral countries own only 13%, or $1400bn. (8)

Lenin writing at the time of the First World War envisaged a situation where European imperialism could shift production to peripheral countries and live off the income from their capital. He quotes Hobson, the English Liberal, who in his book “Imperialism” wrote,

We have foreshadowed the possibility of even a larger alliance of Western States, a European federation of great powers... whose upper classes drew great tribute from Asia and Africa, with which they supported great tame masses of retainers, no longer engaged in the staple industries of agriculture and manufacture, but kept in the performance of personal minor industrial services under the control of a new financial aristocracy... The influences which govern the imperialism of Western Europe today are moving in this direction, and unless counteracted make towards some such consummation... (9)

Lenin remarks “the author is quite right; if the forces of imperialism had not been counteracted they would have led to what he has described.” Lenin saw the workers political movement, namely the Social Democratic Parties, as countering the tendencies of imperialism and was attempting to explain why they had supported the war and had not, in the event, counteracted the forces of imperialism. In fact the alliance envisaged by Hobson and later theorised by Kautsky as “ultraimperialism” proved impossible as the imperialist powers were never prepared to divide the spoils with each other as Hobson envisaged. The outcome was an attempt to divide the spoils by force, which resulted in the First and Second World Wars.

The present situation does, however, bear some resemblances to the “consummation” described by Hobson, in that manufacture is shifting to the periphery while the bourgeois class of the central countries hold the bulk of the world’s capital which allows them to extract surplus value from workers worldwide. The workers in the periphery are becoming an ever more important source of this surplus value. The Tata takeover of Corus, for example, like the majority of mergers and acquisitions, was only partly financed by Tata itself. Over 60% of the capital, or £4.3bn, was provided by the European banks, Credit Suisse, ABN Ambro and Deutsche Bank. (10)

The interest on these loans will be paid out of the profits made by Corus/Tata. This is today’s equivalent to the tribute which Hobson describes the financial aristocracy as extracting from Asia and Africa. The bourgeois class today also has its retainers in service industries who ensure that the supply of surplus keeps flowing in and others who provide minor industrial services. These retainers are, as Hobson notes, definitely not engaged in staple industries of agriculture or manufacture. However, today’s situation is different from that described by Hobson, in that the most dynamic sections in capitalism’s periphery are generating and accumulating capital themselves. This means they are arising as imperialist centres in their own right. As the Tata deal shows they are becoming able to export capital themselves, exploit workers of the central capitalist countries and divert some of the surplus to the periphery. The competition for surplus value, which the more successful peripheral countries are mounting, will inevitably bring these countries into conflict with the older imperialist powers. China, for example, is searching for sources of raw materials and energy, in Asia, in the Middle East, in Africa (11) and elsewhere and is coming into conflict with the US. The situation in which the dominant imperialist powers of the 20th century hold the bulk of the global capital and use this to maintain their global economic dominance, while primary manufacturing is carried out in peripheral countries, can only be maintained by force, and it will ultimately be challenged by force.

The first signs of growing conflict between the US and China can be seen in various parts of the world. In the Middle East, for example, Chinese oil companies are investing $100bn in Iranian liquefied gas projects over a 25 years period, while the US has a policy of sanctions against the Iranian regime and any foreign companies which engage in the Iranian oil sector. China’s interests in Iran mean that it is protecting Iran against the US attempts to impose UN sanctions over Tehran’s nuclear policy. This is considered in more detail in the article on Iran in this edition. The dispute over Sudan and Darfur is also at root a conflict between China and the US over control of Sudanese oil. As in the case of Iran, China is protecting Sudan from sanctions in the UN. A further indication of growing friction is the fact that the US government, despite its professed love of open markets, blocked a takeover of the US oil company UNOCAL by the Chinese national oil company CNOOC. At present these are straws in the wind but indicate a new axis around which imperialist politics is beginning to turn. Such conflicts are the outcome of the capitalist system of production; they are the 21st century’s equivalent of the conflicts which brought Germany into conflict with Britain and France at the start of the 20th century. They are absolutely irresolvable within capitalism and are leading down a path towards further wars.

An international working class against international capital

One of the consequences of the process of globalisation which has occurred in the last 3 decades has been a redistribution of the working class globally. The industrial working class in the central capitalist countries has been decimated. The example of the disappearance of jobs in the UK steel making industry given above is only one example of a general process. The industrial working class in the UK, as defined by the bourgeoisie, has shrunk from about 40 % of the total workforce at the start of the 70s to approximately 15% today. The same has occurred in the US where, in the last 5 years alone, 2.9 million manufacturing jobs have disappeared12. This represents 17% of the total manufacturing workforce. At the same time, however, the industrial proletariat in the peripheral countries has grown massively. The working class has not been abolished, as some bourgeois commentators love to imagine, it has merely been reorganised globally. It still exists as a potentially revolutionary force.

A further consequence of globalisation is that production is more international than ever before. Part of a product may be made in Japan, another part in Europe and the various bits assembled in China. The concept of national capitalism and national industries is thus being eroded. Instead workers today are confronted by capital which is far more international than ever before. The capital which employs workers in the UK, for example, is as likely to be US, Japanese, German as British, it may even be Chinese or Indian. Often the ownership of the capital changes every few years as mergers and acquisitions are for ever concentrating and reorganising global capital. Workers are confronted by capital in general without all the trappings of national flags and patriotism. The situation is in reality a confrontation between the global working class and global capital. The demands of capital, however, are utterly independent of the ownership of the capital. Capital demands profits and it has to extort them out of the working class. This is translated into demands for increased productivity, longer working hours and reduction of benefits. All this can only change with the ending of the capitalist system and the establishment of socialist production.

Charlie(1) The areas where steelmaking was to be concentrated were, South Wales, Sheffield, Scunthorpe, Teesside and Scotland.

(2) By the mid 90s this figure had been reduced to 3.7 man hours/tonne and BS could boast that its productivity was of the same order as that of Germany and Japan.

(3) In the year 89/90 the BSC made £733 million profit.

(4) See UNCTAD report unctad.org .

(5) One such anomaly was the internal reorganisation of the capital of Shell which involved a transfer of $74bn of capital from the Netherlands to the UK. This resulted in the UK becoming the largest recipient of FDI in 2005 and the Netherlands being the largest provider of FDI. The operation appears to have been nothing more than moving numbers from one account to another.

(6) See ISSB issb.co.uk .

(7) Global steel production has increased 6.5 times since 1950. In 1950, 190 million metric tonnes (Mt) were produced, in 1960: 340 Mt, 1970:603 Mt,1980: 712 Mt, 1990:766 Mt, 2000: 851 Mt, 2005: 1133 Mt, 2006: 1250 Mt.

(8) See UNCTAD report unctad.org .

(9) Imperialism the highest stage of capitalism pg 124. Hobson was writing in1902

(10) See Business World businessworld.in .

(11) See article on Zimbabwe in this issue, and, RP 41 Another war in the horn of Africa.

(12) See Craig Roberts counterpunch.org .

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #42

Summer 2007 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.