You are here

Home ›Global Capitalism in Crisis

The More it Grows, the More Unequal it Gets

For billions, especially in Africa and the Islamic world, poverty is spreading, and per capita income is falling. This growing divide between wealth and poverty, between opportunity and misery, is both a challenge to our compassion and a source of instability.

President George Bush, speech to Inter-American Development Bank, prior to Monterrey summit on Financing for Development, March 2002

-

The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses as opposed to the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as though only the absolute consuming power of society constituted their limit.

Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 3 p.484

Lies, Damn Lies and ... IMF Reports

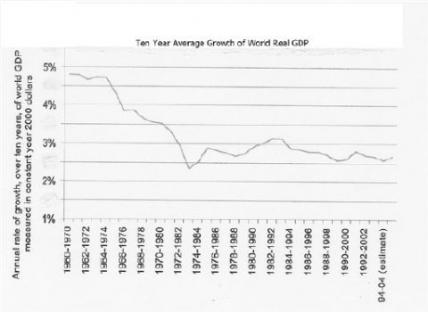

According to the latest pronouncements from those guardians of capitalist economic order, the IMF and the World Bank, the world is becoming increasingly prosperous. In April, the IMF predicted a fifth consecutive year of strong economic growth, at 4.9% “the highest sustained rate since the early 1970s”. We are in no position to query the basis of the figures. However, we are also not obliged to accept the IMF’s interpretation of them at face value. Since capitalism is a system which depends on “growth”, i.e. expanded production of commodities and the further accumulation of capital, a five year spell of continuous growth hardly appears of great significance. The fact that the IMF is reading so much into the last five years - the highest sustained rate of growth since the beginning of the 1970s - not only shows the short-termism of present-day capitalist perspectives, it also betrays anxiety about the sustainability of capital accumulation altogether. Over the last few years, the capitalist world has basically been recovering from the bursting of the high tech stock market bubble which brought down the official growth rate of world GDP to 1.4% in 2001. The “strong growth rates” the IMF is boasting about today therefore have to be seen in the context of a very low starting point: in fact, the fourth very low starting point in a series of mini-booms and serious “downturns” that characterise the long-running crisis of profitability. Put in this longer-term perspective, it is clear that the outlook is far from rosy. On the contrary, for all the economic restructuring, the globalisation of production, the so-called liberalisation of trade and the opening up of financial and money markets, the slowdown in growth persists and the tendency to outright collapse continues to assert itself. The truth is that the collapse of Bretton Woods and the devaluation of the dollar way back in 1971 and 1973 marked a watershed. They signalled the beginning of the downturn in the post-war accumulation cycle and it is an indication of how far that crisis has bitten that the IMF should hail a return to the growth rates of the Seventies as a positive sign.

As one critical re-interpreter of the official figures notes,

Even in the rocky seventies, world growth fell below 4% in only two years: 1974 when it dropped to 1.1%, and 1975 when it reached 1.0%. At the time, such growth rates were regarded as catastrophic, and the 1974 downturn is generally held not only to be the world’s worst since the 1930s but a major reason for the economic policies of the 1980s, with their intense concentration on financial and trade liberalisation. (1)

In short, the revival of world economic growth in the last five years comes nowhere near re-establishing pre-crisis growth rates. The graph here, which traces ten-year averages, shows this. Although the graph only starts with the 1960s-70s decade, thus omitting the first fifteen years of the post-war “long boom” period, the early Seventies’ trough and the subsequent low level of recovery is clear. This graph is based on the official annual averages of global GDP growth. As with all average estimates, the highs and lows tend to be ironed out, and yet the early Seventies’ low point remains apparent.

This low point would undoubtedly be even more apparent if we were able to chart the course of average GDP growth of the world’s richest countries alone, i.e. without including the higher average growth rates of the rest of the world, who of course are starting from a lower base. The figures for such a calculation are difficult to find but, for example, an estimated average for six countries - the USA, Japan, West Germany, France, UK, Italy - for 1974 and 1975 comes out as minus 0.6 and minus 2.25 respectively. (2) In other words, average growth rates disguise the fact that the world’s richest economies went into recession during the Seventies, as was the case in 1981-82, and again in 1991-92 and 2001-02, at least for the US, the euro zone, the UK, and Japan (whose growth has been hovering around nil for the last decade).

Capitalism’s unequal Wealth of Nations

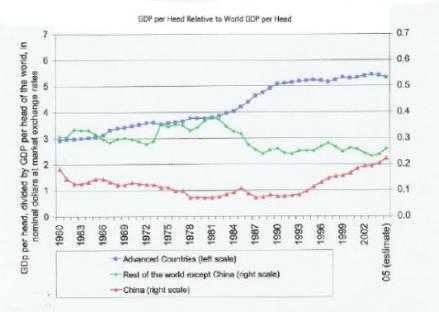

Given the lower growth rates of the world’s richest economies it might be supposed that over decades the poorer countries of the world, with their higher average growth rates, would be managing to increase their share of global GDP. This, after all, is what lies behind the concept of “developing” countries in the post-colonial epoch. Interestingly enough this has never really happened. When there was a significant increase - during the declining growth years of the 1970s, at the start of the capitalist crisis - the trend did not last. After increasing their share of world GDP to an unprecedented 22% by 1980 (due to higher oil and raw material prices), that portion slumped dramatically with the arrival of the 3rd World debt crisis and the accompanying decline in raw material prices. By 1990, the “3rd world” share of global GDP was less than 15%. The IMF’s structural adjustment programme accordingly became part of the wider process of globalisation which has kept capitalism afloat on the basis of the cheapening of commodities (including labour power) and the massive increase in opportunities for financial speculation and gain. Needless to say, “non-advanced” capital’s share of world GDP has yet to regain the heights of the 1980s. Any “catching up” that has happened is largely due to China and to a lesser extent India (10.5% and 8.5% growth respectively in 2006). Substantially, however, there has been no catching up. Although the “3rd world” states enjoy a slightly higher share of global GDP than in 1960 this is more than offset by a doubling of their population over the last half century. Thus, in 1960 the advanced states, with 22% of the world’s population accounted for more than 80% of global GDP. By 2005, the advanced world accounted for only 14% of world population yet still held 75% of global GDP. (3) In terms of GDP per head of population this translates into an even more unequal division of the world’s wealth. Apart from China, GDP per head in the “developing” world is now lower than in 1960. Moreover the gap has opened up recently, under the impact of globalisation which works to the benefit of the capitalist strongholds. As Freeman’s study shows:

The high point was reached in 1982 when average income in the poor countries was 40% of the world average. During ten years of financial liberalisation, this fell to around 25% , where it has remained ever since. In contrast, the average income of the one-seventh of the world living in the advanced countries has risen from three times the world average in 1960, to five and a half times in 2005. (4)

There are plenty of other studies showing more or less the same disproportion between the world’s wealthiest and the poorest states. What they don’t point out is the glaringly obvious: that this is an imperialist relationship where the rich states decide the rules on the basis of their own interests. And the interests of one rich state in particular take precedence over all the rest. In 1948 the administrators of US capital were quite clear about what their post-war mission should be:

We have about 50% of the world’s wealth, but only 6.3% of its population ... our real job in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which permit us to maintain this position of disparity. (5)

Even though the US could not maintain this huge disparity, which reflects its enormously strong position in the aftermath of the destruction of European and Japanese capital after World War Two, the USA still controls a disproportionate share of the world’s wealth. Extrapolating from 2006 GDP and population figures (supplied by the CIA!), the USA now has approximately 4.6% of the world’s population and 27.2% of global annual income. (6)

Within states class divisions are sharpening

Capitalism’s inequitable distribution of wealth is not just about the power struggle between states. There is not a country in the world where GDP is distributed evenly. For all the talk of democracy, capitalism the world over remains a class system of exploitation based essentially on those who own and control the means of production amassing wealth created by the unpaid labour power of the working class. Just how the wealth is distributed within states is the result of the class struggle, both contemporary and historical, as well as the point capitalism itself has reached in the accumulation cycle. (7) Marx argued that the very process of accumulation reduces the variable component of capital so that:

accelerated accumulation is needed to absorb an additional number of labourers, or even to keep employed those already functioning ... (8)

Even so, the increasing productivity of labour power that comes with the development of capitalist production ensures a permanent tendency towards the creation of relative “surplus population” - i.e., the famous industrial reserve army which capitalism has permanently at its disposal.

For Marx, the tendency towards a relative surplus population, is a general law of capitalistic accumulation which takes “now an acute form during the crisis, then again a chronic form during dull times” (9) when the rate of accumulation slows. Until recently this general law was scoffed at by bourgeois social scientists and economists who pointed to the supposed full employment obtaining in the advanced capitalist heartlands during the post-war period. (“Full employment” being defined as less than 1 million unemployed). Now that it is more difficult to claim full employment levels for the heartlands of capital and now that globalisation of production puts wage workers everywhere in direct competition with each other it is more difficult for them to scoff. During the downturn, or crisis stage of the cycle, capital is obliged to further reduce the cost of labour power in its attempt to cut costs and remain competitive. Wages are slashed. Takeovers and mergers become common as capital becomes more concentrated. The threat of unemployment makes it easier for capital to attack the working class. Even so the capitalists find it more and more difficult to find profitable places to invest productively (of surplus value). Financial speculation grows and with fewer productive outlets for their capital, the rich increase their spending on personal luxuries.

It is true that the expansion of the reserve army of unemployed is not just a question of the last twenty years or so. As we have seen, the whole of the post-war period has seen a relative increase in the population of the “Third World” and a relative decrease in their share of the wealth generated by the accumulation of capital. Mounting numbers of increasingly impoverished under- and unemployed have been constantly generated by Third World “development”. However, at the present stage of the accumulation crisis, the grotesque disparity between those who live behind guarded walls and the majority of the rest of the population has become acute and overwhelming. Globalisation, with its structural adjustment programmes on the one hand and injunctions to open up production, trade and financial markets to world capital on the other, has bought a lease of life for capital but has only exacerbated the impact of the crisis on the mass of the population in the capitalist periphery.

More people now live in towns than the countryside. Despite the fact that a growing proportion of migrants to the cities of the “Third World” find no work at all in the formal economy, the exodus to the cities of people forced by wars, the impossibility of subsistence farming, environmental disasters, personal debt, continues. According to a United Nations report in 2002 more than 78% of urban-dwellers in the world’s poorest countries, or 1 billion people, live in slums. This is a conservative estimate. A “slum” for the UN means “overcrowding, poor or informal housing, inadequate access to safe water and sanitation, insecurity of tenure”. Apparently, all these conditions must have to be met for the UN to classify someone as a slum-dweller since, for example, 2.6 billion urban dwellers officially lack sanitation. Not surprisingly, the UN reports 1.8 million children dying each year from diarrhoea and other water-related diseases. Or, as another researcher puts it,

Every day, round the world, illnesses related to water supply, waste disposal, and garbage kill 30 000 people and constitute 73% of the illnesses that afflict humanity. (10)

As for just what “insecurity of tenure” means for people living in makeshift boxes, often in highly polluted or physically precarious zones where there is the danger of the ground collapsing through landslips or flooding, it is difficult to imagine. Yet, every year,

... hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of poor people - legal tenants as well as squatters - are forcibly evicted from Third World neighbourhoods. (11)

In Shanghai and Beijing, for example, 1.5 million and 1 million people respectively were evicted between 1991-97 to make way for new retail developments. Rarely do these events make the news, but earlier this year the BBC news reported the blowing up of a police station by “Naxalites” resisting eviction from their legal dwellings on the outskirts of Calcutta (a prime site for the local government to designate a Special Economic Zone).

| - | Slum % urban pop. | Number (millions) |

|---|---|---|

| China | 37.8 | 193.8 |

| India | 55.5 | 158.4 |

| Brazil | 36.6 | 51.7 |

| Nigeria | 79.2 | 41.6 |

| Pakistan | 73.6 | 35.6 |

| Bangladesh | 84.7 | 30.4 |

| Indonesia | 23.1 | 20.9 |

| Iran | 44.2 | 20.4 |

| Philippines | 44.1 | 20.1 |

| Turkey | 42.6 | 19.1 |

| Mexico | 19.6 | 14.7 |

| South Korea | 37.0 | 14.2 |

| Peru | 68.1 | 13.0 |

| USA | 5.8 | 12.8 |

| Egypt | 39.9 | 11.8 |

| Argentina | 33.1 | 11.0 |

| Tanzania | 92.1 | 11.0 |

However, whether or not the urban poor of the world officially live in slums, they exist in increasing numbers and not always in the periphery. (6% of slums are in the capitalist heartlands, with the biggest population - 100 000 - going to Los Angeles.) Yet, at the same time as the IMF was singing the praises of our wonderful world, the World Bank announced that the number of people living on less than $1 a day had dropped to below 1 billion for the first time! This is the good news! With the purchasing power of the dollar declining all the time, it is a miracle that anyone can survive on less than $1 per day. This is, in fact, a testimony to the number of people who are surviving outside capitalism’s formal economy. These days a $2 (£1) a day yardstick for poverty is hardly an over-estimate. With this measure, even George Bush acknowledged (in the speech quoted at the top of this article) that “Half the world’s people still live on less than $2 a day”. This is an astonishing statement. Together with an item from the CIA’s 2002 World Factbook, stating that:

By the late 1990s a staggering one billion workers representing one-third of the world’s labor force, most of them in the South, were either unemployed or underemployed... (12)

we can begin to get a picture of the extent of 21st century capitalism’s relative surplus population.

The success stories of globalisation, China and India, contribute their share. In China alone, 36 million workers were made redundant between 1996 and 2001 while well over 2 million rural migrants swell the ranks of the urban poor ready to join the super-exploited workforce in the coastal belt’s special economic zones. According to information on the China section of the Worldwatch website (13), China’s National Economic Research Institute reports that in 2006:

the average net income of China’s farmers has increased at a rate of 6.2%, far below the 9.6% growth witnessed in urban areas. Experts note that the income gap within China’s urban areas is even greater than that between urban and rural regions, and is the major culprit behind overall disparities between rich and poor. ... The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences reports that the disposable income of some 60% of urban residents is lower than the national average.

The sharpening of wealth divisions is by no means limited to the world’s poorest states. On the contrary, it is difficult to find a country with greater disparity of wealth than the United States. Officially the US admits to 37 million “poor” - i.e. people living below the average earning rate. But we have seen what calculations based on averages can do. A recent United Nations study, using calculations of household and individual assets (property and financial) rather than just annual income found that the Gini value of wealth inequality - a standard way of calculating wealth distribution - for the United States is 80%. Such a degree of inequality is equivalent to one person in a group of ten taking 80% of the total pie and leaving the other nine to share the remaining 20%. (14)

This statistical illustration may prove to be an underestimation of the real situation. Recent reports, this time of income distribution, reveal the opening up of a huge economic divide. Based on 2005 tax returns, it appears that the 300 000 richest Americans declared an income equivalent to the poorest 150 million (or half the population!). While overall national income increased by 9% (15), the income of the majority of citizens, or 90%, went down by 0.9%. The whole of the increase was thus taken up by the remaining 10%. Such a level of inequality has not been seen since 1928, just before the Great Depression. (16)

It is the latest point in an accelerating process of the rich getting richer as the poor get poorer. The widening gulf between the haves and the have nots that began in the 1970s, grew wider under Reagan until between 1998 and 2005 the richest 0.1% of the population increased their share of the total by 50%.

No wonder Ben Bernanke, chairman of the US Federal Reserve, was led to say in a speech last February,

These days the long term tendency towards greater inequality represent a major challenge for economists and policymakers.

Far from the rosy picture of the IMF and World Bank, the future for the bulk of humanity is clear. Capitalism has absolutely nothing to offer because

ERThe accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole, i.e. on the side of the class that produces its own product in the form of capital. (17)

(1) Alan Freeman, In Our Lifetime: Long-run Growth and Polarisation Since Financial Liberalisation, abstract from paper for Historical Materialism conference, December 2006. countdownnet.infor

(2) From a table based on OECD and EEC figures, in Fitt, Faire and Vigier, The World Economic Crisis, p155, Zed Press, 1980.

(3) The figures are from Freeman’s article, cited above. They are based on IMF statistics and therefore exclude the old East European bloc for 1960 and the so-called transition states for 2005.

(4) Freeman, op.cit., p8.

(5) US State Department Planning Study no. 23, 1948, quoted by us in “The World Trade Organisation, Another Imperialist Agency”, Revolutionary Perspectives 5, Winter 1996-97.

(6) From CIA World Factbook, where US GDP is recorded as $13.2 trillion, c.f. world GDP of $46.66 trillion and US population = 301 million, c.f. a world population of 6.6 billion.

(7) For example, after the 2nd World War the capitalist class were eager to begin a new cycle of accumulation and used the post-2nd World War settlement of a “full employment” policy and the expansion of social welfare measures to buy social peace from a working class demanding recompense for the sacrifices they had made in the war. For an analysis of how the crisis has eroded these conditions for the present-day aristocrats of labour, see our translation of “From Worker Aristocracy to Insecurity”, from Prometeo 14, December 2006, on the IBRP website.

(8) Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, p590, Lawrence and Wishart edition.

(9) Ibid, p600.

(10) Quoted from Eileen Stillwaggon, “Stunted Lives, Stagnant Economies” in Mike Davis, Planet of Slums, [pub. Verso], p142. Unless otherwise stated, the information on slum dwelling comes from this book.

(11) Ibid p98.

(12) Quoted ibid p199.

(14) UNU Press Release on The World Distribution of Household Wealth December 2006. wider.unu.edu

(15) This is a higher figure than for GDP growth.

(16) Marco d’Eramo, L’America dei super-ricchi.

(17) Marx, ibid p604.

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #42

Summer 2007 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.