You are here

Home ›The Crisis is Not Going Away

Second Editorial for Revolutionary Perspectives 05

Our previous issue in June 2014 appeared as the bubble in world commodity prices peaked. When 2014 closed that bubble had well and truly burst. As we suggest in our article on oil and imperialism in this issue, the consequences will be more than economic. 2014 was also the year in which Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century was hailed as the financial book of the year despite an initial volley of withering attacks upon its scholarship (which seem to have withered themselves). Now “orthodox” capitalist economists are rushing to endorse its major conclusion – that capitalism, just as Marx said it would, thrives on inequality. Piketty differs from Marx in that the author of Das Kapital located the contradictory mechanism of capitalism which leads to periodic crises firmly in the process of production (as our article in reply to Gilles Dauvé in this issue argues) whilst Piketty analyses the unequal distribution of wealth which derives from that. Whilst Marx sought to reveal the underlying laws of the system which were not easy to discover, Piketty sticks to the superficial phenomenon of differential wealth for which there are oceans of statistics.

What has made the issue of inequality such a burning one is the clear evidence that since the speculative bubble burst in 2007 the disparity in wealth between the world’s wealthiest and the rest of us has multiplied. Whilst executive pay is 180 times the median wage, wages for all workers have fallen 8% in UK and at the most optimistic estimate claims it will not achieve 2007 levels until 2019.

Piketty, and others, have though looked at the wider historical issue. They point out that after 1945, thanks to workers’ struggles and the need to avoid class struggle in the Cold War, Western states introduced welfare payments and in some cases a state health scheme. In the post-war boom they became increasingly capable of funding a wider social safety net. This reduced inequality. However, when the post-war boom ended in 1971-3 the state was forced to renege a little on this. At first workers organised in large workplaces were able to resist early attempts to make them pay for the crisis and in the middle of the 1970s even managed to push workers share of the national income to record levels. At this point the bourgeoisie were simply printing money and running up a deficit to buy off the struggle. However this only worsened the crisis and brought both inflation and unemployment. The Keynesian consensus in the ruling class collapsed, as did working class resistance under the hammer blows of mass unemployment. As a consequence workers’ wages as a share of national income fell from over 60% when the crisis hit at the start of the 70s to 53%[1] when the bubble burst. Today it is closer to 50%. In the broader historical picture the disparity in wealth has now returned to what it was in 1920 and more austerity is to come. A million public sector jobs are to go in the next Parliament to reduce the deficit and both major parties have committed themselves to doing just that. Whoever wins next May the future is bleak for the working class.

Amongst economists there is much wringing of hands because they can see that the continued drive to austerity will have both social and economic consequences which threaten the very existence of capitalism. No or little growth means that the world’s debt will continue to grow astronomically and reducing the cost of wage labour will continue to be the norm. People on part-time, zero hour and precarious working contracts increasingly have nothing to lose. More and more capitalist pundits are voicing fear that the political and economic alienation of those with nothing to lose will threaten the stability of the system. Yet in truth none of them have a solution to the crisis. Some suggest spending money on infrastructure as an alternative to financial engineering. This would create short-term jobs but the historical record of such projects is patchy. In Roosevelt’s New Deal the USA spent millions of dollars in trying to kick start the economy (1933-6) but the crisis still came back in 1937. It was only the build up to the Second World War and rearmament which really turned the USA (and much of Europe) around. In the end it was only the massive devaluation of capital in the Second World War which enabled a new cycle of accumulation (the post-war boom) to begin.

We have been in an era of permanent low-growth since 1973 and only the various interventions of the capitalist state have managed to prolong, but not solve, this global crisis. They have tried everything from deficit financing to neo-liberalism, from nationalisation to privatisation, from wage freezes to deregulation. They have dismembered old industries and replaced them with a microprocessor revolution which, unlike previous technological revolutions, has had no spin-off in new industries (in fact it has reduced jobs). We have had globalisation and financialisation as capitalism has chased the bottom line by extracting more and more value from workers paid less and less. And to finish it off, globalised capitalism gave us a long speculative boom which ended in financial collapse in 2008. The economists told us at every stage the system would correct itself. Today they mumble that this or that micro-policy might work but are almost as discredited as bankers. Piketty himself says that the only solution is a permanent wealth tax plus a progressive income tax reaching 80% for higher earners. He admits that politically this is utopian as the ruling class will never agree to such a decline in income. We would argue that economically it won’t work any better than the other neo-Keynesian schemes he correctly rejects but like social democracy in the past it would ensure greater social stability for the capitalist system.

What capital really needs is a massive devaluation of current values. However no capitalist is prepared for this to happen to their own capital although they are quite happy to see it happen to their rivals. And this lies behind the current imperialist encounters from Ukraine to the Pacific. The ultimate capitalist solution is war no matter what individual capitalists might desire. The only alternative is for the sleeping giant of the world’s working class to begin to fight for its own interests again. Accepting austerity is not just a short-term burden but can only lead to worse consequences in the long-term. If the capitalists impose their agenda on the world then humanity itself will be threatened.

But fighting austerity is only the start. Only a conscious working class which has regrouped and reorganised itself politically with a clear revolutionary programme can stand in capitalism’s way. This means we have to learn from our own past. This is why the publication of Onorato Damen’s reflections on the political failure of Italian revolutionaries to found a Communist Party at the Bologna Congress in 1919 is neither a simple act of homage nor a piece of historical nostalgia. It is part of our contribution to the theoretical fight for a new international organisation of the world working class. As 1919 showed, even an extremely militant class cannot win unless it gives itself the right tools. Only by understanding our past defeats will we prepare the way for future victory against a system which brings only exploitation, terrorism, poverty, and war.

The two articles here are editorials from Revolutionary Perspectives 05. It contains further articles on the fall in the oil price and what it means for imperialist rivalries, a reply to Gilles Dauvé on the problems of the transition to communism, and an article by Onorato Damen on the failure of the Bologna Congress of 1919. The issue will eventually be posted online but for those wishing to read the articles now or wishing to support our work it can be purchased for £4 (postage included) by mailing us here for details of payment.

Footnotes

[1] tuc.org.uk

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #05

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

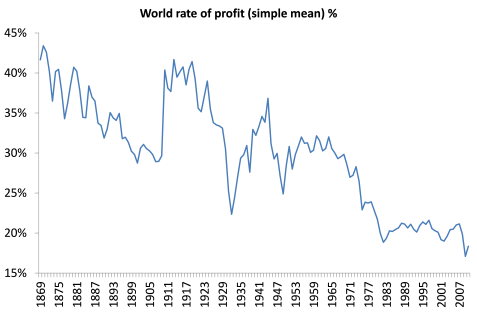

Id like to ask a couple of questions about the start of the article. Firstly, it say "When 2014 closed that bubble had well and truly burst" - this is quite a strong statement but i dont think its meaning is clarified. What are you expecting to happen in consequence?

Also i would like to know a bit more about the stats used to prepare that graph on FROP. Obviously it has to be an approximation but on what are these figures is it based?

Link

Thanks for the questions. This is an editorial which is referring to the other articles in RP05 which is just out (the one in question is on the oil price collapse). We are at this point talking about the global collapse in world industrial commodity prices in the second half of 2014 in general (only nickel has bucked the trend). The full article explains how speculation kept a commodity price bubble going even when there was no increase in consumption (demand and consumption turn out to be different). The full article will be up at the end of the month but subscribers have it now. The graph is for illustration purposes only but is taken from Michael Roberts Blog (well worth a visit). We don't know who he is but he has a whole series of articles demonstrating the case behind the graph.

Thanks for the reply. Ive have a look at the article now but need to re read. Also found the link to Michael Roberts and, phew, plenty of reading for me their too. This should keep me quiet for a while cheers.