You are here

Home ›Oil and the Shifting Sands of Imperialism

The collapse in oil prices represents a significant blow for global speculation and thus a further intensification of capitalism’s crisis. It also heralds an increase in imperialist tensions with as yet untold consequences for the struggles, not just in the Middle East and the Ukraine, but in an increasingly competitive and aggressive wider world. The following article examines the meaning of this collapse and the developments which brought it about. The key question is whether lower oil prices could lead capitalism out of its present crisis. We think this will not occur. The text also contrasts the position of OPEC in the 1970s to that today. The attempt by the Saudis to regain market share by bankrupting “tight oil” production, which is mostly in the US, through sustained lower prices sees the Saudis acting against the interests of their imperialist master for the first time. This can only represent a symptom of a more general US loss of hegemony in the Middle East. This has been most clearly visible in its contradictory position in Iraq and Syria and its withdrawal from Afghanistan. The biggest beneficiary of lower oil prices is likely to be China but as we also argue here it is not without its own problems. 2015 will thus be a year of crisis and increasing international tension which will bring misery to millions, once again revealing that the capitalist system is not the final resting place of history.

The Oil Price Collapse

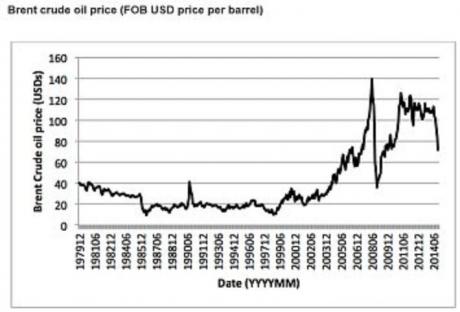

The dramatic 50% drop in the world oil price in the second half of 2014 has sent shockwaves through the world economy. However, when you think about it, the fall is not so strange. What is really odd is that in the face of a global recession the price has remained so high for so long in the first place.

After a brief blip in 2009, following the bursting of the speculative bubble, oil prices continued to surge to levels never seen before. In fact it appears that demand has never faltered. In the third quarter of 2012 world output reached 90 million barrels a day. It has not gone below this ever since and, according to the International Energy Agency is currently close to 94 million barrels a day (1). This continual “demand” and hence high price is in itself slightly mysterious given the decline in production growth in the developed world.

The answer appeared to lie in the appetite for more oil from the “developing world”, in particular China and India. Or at least that’s what they kept telling us. In fact it gives an extremely misleading impression. Even for China and India, economic growth has slowed down. Both had double digit growth before 2008 but now they have slipped to 7% and 4.5% respectively. For China the slowdown came quite quickly in the wake of the 2008 puncturing of the global speculative bubble. In fact what happened was that the Chinese Communist Party recognised that economic disaster beckoned if they did not act. As a result they used the 4 big state banks to lend record sums of money to stimulate the economy mainly through a housing bubble in China itself (2). In India the trajectory was slightly different with as much as 12% growth as late as 2012. However in 2013 this nosedived to around 4% and has only reached about 5% under the new Modi government, despite the great hopes that were pinned on his ability to free up the private sector. Now both countries have revealed deeper economic problems.

In the third quarter of 2014, China’s gross domestic product expanded 7.3 percent year-on-year, slumping to a five-year low. The slowdown was driven by lower property investment, dwindling credit growth and weakening industrial production (3).

And India is no better off as this report from the Financial Times makes clear.

Indian companies, furthermore, were heavily indebted and more than a third did not make enough money to cover their interest payments … The banks, in turn, were exposed to high levels of bad and doubtful debt - 11 to 12 per cent of total assets (4).

This signalled that the great commodities boom in the so-called BRICS since 2000 was coming to an end and not just for oil. The iron ore price fell more than oil in 2014 and only nickel amongst industrial commodities has avoided a sharp drop. But why is the commodity boom only ending now and not in 2008-9? The answer lies largely in speculative activity. In some respects with commodity trading there always is speculation.

Speculation and Debt

Oil is typical. Oil prices which are fixed on the NYMEX (West Texas Intermediate (WTI) index) for the US or for the world in the more important ICE (Brent Crude Index) in London have long since been unconcerned about present needs (5) but only with future prices. They in fact establish what the price will be in 18 months to 2 years time. The complication does not stop here. As the price contractors are basically gambling on a prediction they also have to ensure that they have not got it completely wrong so they engage in hedging (6) (just like a bookmaker who finds they have taken in too much money on one horse and lay the bets out with other bookmakers) by parcelling out that risk to others.

And this is only the simplified beginning of the process since the world financiers keep coming up with more and more elaborate ideas for pooling this risk as well as sharing the benefits. Credit derivatives, default swaps and all the other fancy names they have given to bundles of debt are the result. Over the last few years financial speculation has not stopped but they have discovered, or rather renamed, some of these instruments. What used to be called junk bonds are now sanitised as “High Yield bonds” (i.e. high risk bonds) and instead of CDOs (collateralised debt obligations) we now have collateralised loan obligations. CLOs are a type of bond that bundles together cash flows from loans made to highly indebted companies with safer investments and then slices them according to risk. Both have played a major role in the speculators’ strategies. In truth there is nothing new here.

What is different is that there is a new element in this speculation. Until 2002 only 5-10% of commodity trading was “attributable to investors” (i.e. managers of investment funds who have no real interest in long-term productive investment only in the amount of revenue they can acquire in the shortest time via the various equities and bonds issued) but after this the figure suddenly leaps to 30% and with it the rapid boom in commodities. And where better to speculate than in the one commodity that is the backbone of nearly all economic activity on the planet?

The vehicles of this increased speculation have been the traded equities and bonds used to finance shale oil and gas exploration and production in US. This is particularly noticeable in the category of “tight oil” which includes fracking, horizontal drilling, deep water drilling and heating up oil sands with steam to extract usable crude as they do in Alberta, Canada. They are “tight” because they are not as cheap and easy as conventional methods for extracting the crude and have lower profit thresholds. The rise in oil prices gave the green light to private equity firms which were sitting on piles of capital but, given the low global rate of profit, with few places to invest. As the Wall Street Journal put it:

For the most part, private equity has been a friend to shale drilling, which emerged about a decade ago. Wildcatters combined sideways drilling done miles beneath the surface with a rock-cracking process called hydraulic fracturing to unlock vast reserves of fuel. Private-equity firms were poised to profit. At the time, major oil companies had turned away from the U.S. in pursuit of far-flung prospects, and bank financing all but dried up during the recession. The financiers, meanwhile, had piles of cash raised before the financial crisis for buyouts (7).

As a result of this investment the US alone has added 4 million new barrels of crude oil per day to the global market since 2008. And yet until last June it seemed to have no effect on prices. Some have tried to argue that the politico-economic conditions in 2014 suddenly changed. They point to the renewal of Libya’s oil exports as the rebels have opened up a couple of ports but with IS seizing Syrian and Iraqi oilfields, with a continuing dispute between the Kurdish Regional Government and Baghdad over oil revenue (and thus oil flow) (8), with Iran still hampered by sanctions, it is difficult to see how things have improved much here either.

The initial fall has to be the result of doubts amongst the speculators. In the first place they based their gamble on forecasts for an increased future demand. In 2013 the financial magazines were full of articles about how oil production would never keep up with Chinese demand. But halfway through 2014 it was clear that this was not picking up as they had expected. The recovery was not happening. Those dealing in the futures markets began to notice that though a lot of oil was getting sold this was because the countries pursuing energy security were stockpiling it. This becomes clear when you analyse the difference between “demand” and “consumption”. Even though China and India’s demand was increasing they were not actually using it all but increasingly storing it (largely for energy security reasons). According to the US Energy Information Administration’s Short Term World Outlook Report (Douglas-Westbrook analysis) their actual consumption began to stagnate and then decline during 2013 even though demand continued to increase. Initially oil, finance and other energy organisations paid little attention. Those involved in oil investment had a vested interest in not noticing and pretending that oil was still on the up.

However in 2014 when they saw that crude oil was increasingly ending up in storage tanks at key locations, not just on the other side of the world but in the USA itself, then warning signals were triggered. The West Texas Intermediate (WTI) index for sweet American crude takes its lead from the oil storage facilities at Cushing, Oklahoma which were the largest in the world when built, taking about 41 million barrels. However the facility has been expanded and now holds something like 69 million barrels. By the end of 2013 oil analysts were noticing that the reserves were mounting and getting close to a critically high level (i.e. the tanks were almost 80% full – and they always try to keep 20% free). This sparked the original price drop last June but was not the main cause of the steep decline that followed. For the answer to this we have to turn to Saudi Arabia and OPEC.

Saudi Arabia, OPEC and 1973

In the history of oil production and pricing since the 1970s one factor stands out. This is the role played by Saudi Arabia and OPEC in maintaining relative price stability. The bedrock of this system dates back to 1945 when Roosevelt was on his way back from Yalta. Sailing on the USS Quincy in the Suez Canal he met with Abdal Aziz, the Saudi monarch (9). It was not the first contact between the two sides. US-Saudi relations began in 1937. In that year the discovery of oil by the US firm, Standard Oil, set the US on course to an understanding with the Wahhabite autocracy of the Saud family in the Arabian peninsula. It was the only Middle East oil country where the US had managed to muscle in over the British (who had assisted the Saud’s rise in the 1920s until they finally set up the kingdom in 1932). As Standard Oil (soon to become the Arab-American Oil Company (Aramco), and sharing profits with the Saudis) began to find more oil during the Second World War the significance of Saudi Arabia to US imperialism had become obvious. The deal was that the US would give unstinting military support and a secure market to the Saudi regime in return for an assured supply of cheap oil. And cheap it was throughout the post-war boom. In fact the oil price fell in real terms as a gentle but continuous inflation increased costs in almost every other aspect of economic life. By the end of the 1950s the US was in a relatively luxurious position. In 1960 it encouraged the formation of OPEC (the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) of 12 of its international oil-producing friends (including Iraq, Venezuela and Iran) (10). At this point the world had not taken much notice of these countries getting together.

The picture changed with the end of the post-war boom as the immanent laws of capitalist production once again began to assert themselves. We have explained many times how they operate specifically in response to the tendency of the rate of profit. Anyone wishing to investigate further can start with the links cited here (11). All we will say here is that the reappearance of the crisis of accumulation was the most significant turning point in world history since the Second World War. All the cosy assumptions that the longest secular boom capitalism had ever seen would go on for ever (as Keynesian economists believed at the time) were shattered. The clearest signal that the party was over was Nixon’s abandonment of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971. At Bretton Woods in 1944 the US had agreed that the US dollar would be always equivalent to $35 an ounce. It was thus as “good as gold” and would be the fixed currency of the so-called “free world”.

However, US GDP plunged by 4.2% in 1970 (12) and the economy went into recession. US Treasury outlays increased, as did both the budget and trade deficits. As more and more dollars were printed to cover the deficit (a fact made worse by the mounting costs of the Vietnam War) the US state realised that it could no longer cover all the promissory notes it had issued with its gold reserves. Hence in 1971 the US abandoned the gold standard and floated the dollar. With flotation came devaluation and Nixon realised that the US was “over a barrel” economically in another sense too. In 1945 the US had been the biggest producer and trader of oil in the world. This peaked in 1970. In that year US oil production stopped growing and the US Government’s secret survey of the prospects (carried out by James Akins who after 1973 became US Ambassador to Saudi Arabia) concluded that new wells were unlikely to come onstream in the short term, especially if oil prices remained relatively low. The US Government thus faced a double whammy. Not only was the US likely to import more and more oil over the foreseeable future but a devaluing dollar would make this more expensive. The dollar was the bedrock of US dominance of world markets because of its guaranteed statutory value. Now other states (including oil producing states) might find they could no longer rely on the dollar. The fear was that they would turn to other currencies thus further reducing the value of the dollar. This would have been calamitous for US domination of the world economy.

Nixon thus proposed a new military alliance with the Saudis in return for them permanently making all oil transactions in dollars. King Faisal agreed and what came to be known as “petrodollars” were born (13). US policy ever since has been to try to ensure that the world continued to use these dollars for most of its transactions. This has allowed the US Treasury to print money which need not circulate in the US and thus create inflationary pressures. In effect the rest of the world would be paying for the crisis in the USA. And as John Authers pointed out in the Financial Times

… ever since the postwar version of the gold standard ended in 1971, with President Richard Nixon’s decision to end the dollar’s fixed price in gold, oil has been its closest replacement as a store of value in the world economy (14).

This has no doubt encouraged Saudi Arabia to remain true to its word, not only by sticking to the dollar in pricing, but even investing massive amounts of the dollars it receives in the US economy.

The Oil Crisis of 1973

Despite the mythology Saudi Arabia was still sticking to the deal in 1973. 1973 was an important year in global history. Whilst the popular press has it that in that year the Arab oil embargo created the economic crisis that brought the post-war boom to an end, in reality it was the other way round. The oil producers had been cheated for years in the boom. While nominal oil prices remained roughly the same despite runaway demand, oil revenues were actually declining in real terms due to annual inflation of 1 or 2% in the world economy. The oil embargo may initially have been politically motivated but it morphed into a demand for fairer oil prices. The same demand was being made by all commodity producers in the so-called developing world but only the oil producers had such a strategic weapon in their hands to do anything about it. This was when the world first took notice of OPEC.

The great problem for US imperialism in the Middle East was that its policy rested on unquestioning support for two states, Israel and Saudi Arabia locked in opposite sides over the dispossession of the Palestinians. Throughout the Cold War the US managed it fairly well by playing on the Saudi monarchy’s fear of communism. However after the Israelis won the Six Day War in 1967 they continued to occupy parts of Egypt and Syria as well as Gaza and the West Bank. By 1973 the Arab pressure for Israel to withdraw had mounted and one weapon that Faisal of Saudi Arabia deployed was the threat of an embargo. He began threatening at the beginning of the year but did not actually impose it until a meeting of OPEC in Vienna after the Yom Kippur War began in October. For once, Israeli intelligence had failed and Syrian and Egyptian forces caught the Israeli Army by surprise. However as the Israelis began to recover lost ground the US delayed a UN resolution on a ceasefire and this became the provocation for the calling the embargo. At the same time other Arab states in OPEC like Kuwait and Iraq, announced that they would reduce production by 5% a month until Israel withdrew from occupied lands.

The panic this caused in the West is legendary, with unemployment rising, short-time working and long queues at petrol stations. But in truth this was not the result of the embargo. There had been long queues earlier in the year in the US due to Federal Government measures to reduce oil consumption in the wake of falling US production (15).

The embargo itself lasted only 5 months and was never properly carried out. No other significant oil producer (especially Iraq and Iran) ever stopped supplying the US with oil. Even Saudi oil continued to discreetly flow to the US via tankers from Bahrain (from where the US Army in Vietnam was supplied). And in any case, given how the oil markets worked, an instant embargo was impossible, since much oil was already in tankers on its way to the States. Even the threatened reductions of 5% a month by other Arab states were abandoned after only two months (mid-December 1973).

Whilst Nixon’s envoy Henry Kissinger recorded in his memoirs that his failure to believe that the oil embargo was for real was a “blunder”, many commentators have challenged this interpretation. According to the famous Saudi Oil Minister and OPEC negotiator Sheikh Yamani, the US actually wanted a price rise at that time. Then, as now, a higher price for oil would give them sufficient profit to invest in “tight oil” production in the States. Yamani had at first not really believed that the US were comfortable with this but was told to visit the Shah of Iran who told him that the Americans wanted a price rise. In an interview with two Guardian journalists in 2001 he stated that in 1973,

‘I am 100 per cent sure that the Americans were behind the increase in the price of oil. The oil companies were in real trouble at that time, they had borrowed a lot of money and they needed a high oil price to save them.’ He says he was convinced of this by the attitude of the Shah of Iran, who in one crucial day in 1974 moved from the Saudi view, that a hike would be dangerous to OPEC because it would alienate the US, to advocating higher prices. ‘King Faisal sent me to the Shah of Iran, who said: “Why are you against the increase in the price of oil? That is what they want? Ask Henry Kissinger - he is the one who wants a higher price”.’ Yamani contends that proof of his long-held belief has recently emerged in the minutes of a secret meeting on a Swedish island, where UK and US officials determined to orchestrate a 400 per cent increase in the oil price (16).

No-one has seen these minutes but there is circumstantial support for Yamani’s view. In an OPEC meeting in Algeria in 1972 Nixon’s energy advisor James Akins had already suggested a rise to $4 or $5 a barrel (equivalent to a 40% increase at the time). The Shah of Iran, the US strongest supporter in OPEC, actually advocated pushing the price to $20 and it was Yamani himself who fixed the “compromise” figure of over $11 or a rise of about 400%.

The problem for the US is that today it has few friends able or willing to do this now. In past periods when the oil price has fallen the Saudis have always been the first to cut. After all, the Kingdom has 25% of the world’s oil reserves and 85% of spare production capacity. Previously it has used, or not used, the latter to keep prices relatively steady. However, in 2001 Saudi Arabia cut production to keep prices up only to find their market share was simply taken by other producers without it raising the oil price. Saudi Arabia thus is no longer prepared to be the reservoir to stabilise prices to satisfy the US. It is no longer worth it. However this time it has gone further. Not only has it not cut its production but ever since the prices started to fall it has accelerated that fall by increasing output. This is clearly a policy and in November, Saudi Arabia succeeded in getting the rest of the OPEC club to go along with it, despite the fact that all of them would prefer higher prices to balance their budgets. OPEC output has been above its stated quota limits for most of the last six months. Ironically the policy is reminiscent of US monopolies like Rockefeller’s Standard Oil who in the US oil boom spent their reserves to force down prices to bankrupt rivals and then bought up their production at knock down prices. Saudi may not be planning on buying anyone else’s productive capacity, but they are making a decisive and strategic attempt to destroy “tight oil” in the US (including shale) once and for all, even if this means a sustained period of low prices.

The Consequences for Oil Producers

Other OPEC members have little choice but to follow them. Many commentators describe OPEC as a cartel but this it has never been since it has never included all major oil producers (the USA and USSR/Russia for example). It is a club which was set up in entirely different circumstances to today when the world economy was booming. In fact many of the commentators who still call it a cartel then go on to say it is ineffectual. They don’t seem to see the contradiction. In fact the OPEC producers have realised for some time that they are no longer in the same fortunate position as they were in 1960 or even 1973. However they have no option but to follow the Saudi insistence that if OPEC producers cut production to increase prices other non-OPEC producers will simply fill the gap as they have increasingly done over the last 20 years. In short, OPEC can do nothing but agree to keep on producing the same quotas despite the strain this will cause for many.

Low prices are not painless for Saudi Arabia itself. Since 2005 King Abdullah, worried about threats to the monarchy from his own youth, has done more than any previous monarch to establish schemes to give Saudis jobs (rather than rely on foreign workers as in the past). He spent $112 billions on social programmes in 2011 alone (17). This was partly a recognition that many unemployed Saudi young men were heading off to the jihadists movements around the world (see the editorial in this issue) and partly also a recognition that there has to be something beyond oil to sustain the Kingdom in the future. This means that state expenditure is higher than it has ever been which is why as late as June 2014 oil minister, Ali al Naimi, was loudly proclaiming that $100 a barrel was a fair price. Saudi Arabia has huge financial reserves (these are estimated at anywhere between $500 billion and $900 billion). The Saudi rulers are thus prepared to run a budget deficit which is predicted to be 14% if oil is at $60 a barrel for some time, in order to cause even more pain to their rivals. The Riyadh regime has no sovereign debt so obtaining loans from international financial markets would be no problem. In a remarkable volte-face oil minister, Ali al Naimi, is now saying he is prepared to carry on producing the same amount of oil even if the price falls to $20 a barrel (18). This is no piece of bravado as Saudi production costs are less than $10 a barrel. Few can match that (19).

This means that the graph at the top of this article (which is only one version of the oil price that each country needs in order to balance its budget – there are others and they don’t all agree on the precise figures) needs to be interpreted carefully. However as a rough guide this it shows that not one oil producer can be said to be happy with a price under $60.

Low prices do have a disproportionate impact on some rather than others. Nigeria and Venezuela are so much more dependent on oil revenue that the crisis will be much more profound in those places. Nigeria’s economy so recently proclaimed itself as the largest in Africa but the declining oil price has hit export earnings (oil accounts for 90% of export earnings), government revenues (60% of which come from oil) and the currency (the naira) is falling rapidly despite an 8% devaluation. In Venezuela, where social welfare programmes are based on the previous high price there is a sense that something has to give. Oil accounts for 96% of export earnings and estimates are that every dollar drop in the oil price costs Venezuela $700 million). Some analysts suggest that Venezuela needs a higher oil price ($130) than the table above suggests. In addition, the economic mismanagement of the Maduro Government over inflation and basic supplies means it looks like there are tough times ahead for the so-called “Bolivarian Revolution” (20).

Despite the evidence presented here, there are some who do not believe that the motives of the Saudi regime are simply economic. The most vociferous of these is David Gardner in the Financial Times. He argues that the main target is Iran, and the motive, religion.

The Wahhabi nation’s visceral hatred of its Shia rivals should be factored into the equation … the more threatening regional rival to the House of Saud and its absolutist brand of Sunni Islam is Iran – which, since the 2003 US-led Iraq invasion installed a Shia government there, has forged an Arab Shia axis from Baghdad to Beirut, with influence, too, in Saudi neighbours Yemen and Bahrain.

This is undeniable and the fact that the US and Iran are now fighting the same Wahhabist-Sunni enemy in Syria and Iraq in IS will not have been lost on the Saudi regime. But the ruling elite are not so stupid as to think that lowering the oil price will bring down the Iranian regime (although it might give the ayatollahs pause for thought over the massive financial aid they are sending to their allies in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon). And it might even be counter-productive.

If Iranian options are restricted due to falling oil revenues then this could force the Iranian regime to do a nuclear deal with the West and thus have sanctions lifted. This would then lead to Iran getting investment from the West and greatly strengthen its imperialist position. The Iranian “reformists” (i.e. those seeking a deal with the West) also think that Saudi oil policy is aimed at them. President Rouhani denounced the drop in the oil price as “treachery” (without specifying the traitor or the deed) and there is no doubt it will make the position of his government weaker (He has been carrying out economic reforms to undo some of the stupidities of the previous Ahmedinejad presidency but the new oil price will undermine this as the table above shows). In short, it could go either way. Rouhani might cut a deal with the US but equally he might be paralysed for lack of revenue and this would open the door to the hardliners (in the Pasdaran or Revolutionary Guards) (21) who are just waiting for the chance to get rid of him. Iran wants and needs the oil price to go back up, but for the moment is also a prisoner of the OPEC decision, and any break with OPEC would only make things worse for the Iranian oil industry.

The Threat to Russian Imperialism

Beyond OPEC there is the particular case of Russia. The Russians at first also seem to have increased oil production and through Lukoil, the main oil company, gave discreet diplomatic support to the OPEC states’ stance in not reducing supplies in the summer. It seems that they too saw a long-term threat from shale oil in the US so were initially prepared to go along with the Saudi policy of not ceding ground to other producers. Economically though this was a dangerous game for the Putin regime. Russia is much more dependent on oil exports (as opposed to gas the price of which, in any case, has now also fallen to a record low on the NYMEX) for its revenues than is sometimes supposed. It gets 33% of its foreign exchange from sales of crude and also sells about half as much again in refined petroleum products. Russia is already facing enough economic problems thanks to sanctions which were said to be causing a loss of $40 billion a year in November (22). The economic pressure from sanctions and falling oil revenues is leading to flight from the rouble which has only been floating on foreign exchange markets for a couple of months. Much of this is because rich Russians are selling them for dollars. The central bank has reserves but is not prepared yet to use them to support its own currency. Instead it decided to raise interest rates to 17% but this did little to arrest the decline of the rouble which fell to 50% of its October value in December 2014.

Rosneft, the heavily indebted Russian oil company, has asked to borrow $40 billion from Russia’s sovereign wealth fund but was not given it. Instead it has issued rouble denominated bonds worth $11 billion which it is believed were only bought by the largest state banks. According to Sergei Guriev this has been accompanied by some dubious financial practices. Not only did the investors charge Rosneft a ridiculously low interest rate but they were then allowed to use the bonds as collateral to borrow even more money from the central bank (23). Russia has no current account deficit but it does have historic debt. With $120 billion of that debt due for repayment in 2015 it is not surprising that the rating agencies have downgraded Russia’s sovereign credit rating to junk. Little wonder that in November the Russians had changed tack over the oil price and tried to sound out the OPEC meeting about some sort of production cut agreement but without success (24).

According to Putin the whole business has less to do with economics than it has with a Western plot (along with sanctions) to once again reduce Russian power and influence. Only last June Putin signed into being the Eurasian Economic Union in Astana (capital of Kazakhstan) with Kazakhstan and Belarus. This was one response to the sanctions imposed by the West. Theoretically allowing free movement of labour, capital and goods between member states it is believed that it will mainly benefit Russia given its overwhelming economic clout (25). But Russia’s standing as an imperial power in the states of the former USSR have taken a hammering as their currencies have fallen dramatically in the wake of the rouble’s decline. Belarus, which has 59% of its imports and 35% of its exports with Russia, was already a victim of Putin’s retaliatory ban on western food imports. Now as the Russian rouble falls it has been forced to raise interest rates to 50% and impose a 30% tax on buying foreign currency to try to hold its own currency up. Despite these drastic measures it still fell by 13.3%. It was not alone. All the “stans” apart from Turkmenistan lost heavily with the Kazakh tenge leading the way in a 15.2% fall. The Moldovan leu fell the most to 17.1%. The only consolation for the Kremlin was that hostile states such as Georgia (8.7%) and Ukraine (47.9%) also got sucked into the vortex of currency falls.

There is no question that 2015 looks bleak for Russia. Even a (former?) Putin ally, Alexei Kudrin, has forecast that Russia will face a “full-blown economic crisis next year”. He predicted that if the price of oil stayed at $60 a barrel the Russian economy would contract by 4% (the Russian central bank actually forecasts 4.7% at this price). Already the central bank has had to bail out Trust Bank (so far injecting $2 billion into it) and is planning an $18 billion recapitalisation of the whole financial sector next year (26). Putin continues to put a brave face on it even as those impoverished London-based oligarchs squeal about the hundreds of millions they have lost with the fall in the rouble. The poor things though would be better to remain silent as in the particular state capitalist regime which is now Russia the loss of state patronage (and Putin’s support) can be costly, as Mikhail Khordokovsky’s years in gaol prove. Putin is still popular, riding on the fact that life in Russia has improved dramatically since the disastrous Yeltsin years. His nationalist narrative in restoring Russian pride by his interventions in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and now the annexation of the Crimea has reversed years of Russian retreat in the face of an ever more arrogant advance by Western states. There is no question that this policy, as well as his support for the breakaway entities in Eastern Ukraine, has boosted his popularity. And he will continue to play on this by blaming all the impending economic problems on the West. He set the tone in a recent press conference;

… he compared Russia with a bear .. “They will always try to put it on a chain,” he said. “As soon as they succeed in doing so they will tear out its fangs and claws.” That, he said, would leave it nothing but a “stuffed animal” (27).

Desperate sounding stuff but it represents a kind of truth for the Kremlin. Putin cannot back down from the game of brinkmanship that he is playing, either politically or economically. He counts on disunity between the EU and the USA for ultimate success but increasingly he is driving his opponents together. It is a dangerous game and the oil price collapse might threaten to bring down the entire economic edifice. Still when faced with estimates of a 5% economic contraction next year (with a further 3% the year after), pro-Putin spokesmen just give a shrug and say that the Russians have suffered worse in the past. This gathering economic storm will do nothing to halt the war in Eastern Ukraine or give much scope for negotiations. And with a global economic slowdown leading to all political leaders seeking refuge in increasingly nationalist rhetoric, tensions can only mount in 2015.

And Consequences for the Global Economy?

As the main Saudi aim is to reduce US shale production, just how dangerous is the Saudi/OPEC policy for shale producers? Journalists have speculated about as much as the financiers on that one. With some there is almost a sense of ideological bravado as they argue that shale production can still be profitable at $50 a barrel due to new (but unspecified) technological advances. Others insist that the game is up for shale at under $80 or whatever price they think. Our own view as expressed in our previous article on this subject takes us back to the speculation we mentioned at the beginning of this piece.

Even the much-trumpeted energy independence, which according to the most optimistic forecasts would be achieved at the earliest by 2050, appears to be more a mirage than a hope. It is much easier to see shale gas as yet another speculative bubble in the US. In fact, thanks to the interest of speculative financial capital on Wall Street, data on US reserves of shale gas may have been exaggerated 400%.

Almost certainly hidden behind the euphoria about the exploitation of shale gas deposits lies the fact that current production comes from just two deposits of shale oil (the Bakken Shale in North Dakota and Montana and the Eagle Ford deposit in Texas), whose production peaks are concentrated in very limited areas, and five other fields of shale gas (28).

In short the shale revolution is neither as wide nor as deep as its promoters maintain (29). There seems to be a recognition by the more involved pundits that there will be blood (i.e. some bankruptcies amongst shale producers) but in the good old US tradition this will only allow their less-indebted competitors to buy up their capital cheaply.

In the US shale oil industry, where growth has been fuelled by borrowing, Pearce Hammond of Simmons & Co, the investment bank, says “companies that have good assets but that don’t have good balance sheets” will likely fall to acquisitions. Large oil companies are already reviewing potential targets, hoping to use their financial strength to pick up assets and companies at attractive prices (30).

In other words we are in for the next round in the historical game of oil monopoly capitalism. The big oil companies will attempt to pass on the pain to the oil services industry. The great thing about being an oil major (monopoly) is that you contract out the real work to lots of smaller companies and then pull the plug on them when times are bad. The UK should expect a lot of redundancies and wage cuts in places like Aberdeen where many of these contractors are based. This will also trigger some concentration and centralisation of capital in the supply companies.

Many are talking up the benefits of an oil price fall. Leading the way is the IMF’s Christine Lagarde. She argues that the economic benefits of the lower oil price will boost global growth by 0.6% for the next two years (with beneficiaries including non-oil exporting nations like India and China as well as Western “consumers” who will face lower inflation) as happened the last time oil prices fell in 2008-9 or back in 1986. However, there are some who recognise that things could be different this time. In fact, if the world goes into a period of stagnant or falling prices generally in the wake of commodity price falls in 2014, then there is no incentive to spend, as is the norm when inflation will eat away at savings. If that happens there will also be little economic growth and little investment. As it is the amount of debt washing round the world since 2007 has not diminished but has actually almost doubled to $60 trillion (31). With no inflation and little growth (the financial markets have now realised that much of China’s current growth is based on unsustainable financing of technically bankrupt firms) it is difficult to see how this trend can be reversed.

Which brings us back to the original question about speculation. Given that the fundamental crisis of the falling rate of profit can only be addressed by a massive devaluation of capital and this no owner of capital naturally wants to do (but wants everyone else to do) there are few outlets for profitable investment. Hence capital shifts from one category to another trying to achieve the maximum return. This explains why the stock markets have remained ridiculously high even though there is no economic performance in real terms to justify the current index. Shale production is already beginning to register a downturn.

Many investments remain in the black. But the nearly 50% drop in oil prices since this summer has wiped at least $12.7 billion of value from private equity’s holdings, based on the stock moves of nine exploration and production companies that represent some of firms’ largest publicly traded energy positions (32).

So much for direct investment, but what are the wider consequences for the collapse of the oil price on this latest speculative bubble?

The shale surge has been built by borrowing: companies have typically spent more on drilling and completing wells than they have generated in cash flows and over the past decade about $163bn worth of high-yield debt has been issued by US oil and gas producers. Some have relied much more heavily on debt than others, however (33).

High yield debt is as we explained above the new name for “junk bonds”. The question will be who will pick up the tab for the ones that do fail. As banks have been reluctant to further endanger their existences by backing shale it has been left to private equity and hedge funds to take up the challenge.

Some hedge funds were already in trouble before the oil price registered.

Hedge funds are shutting at a rate not seen since the financial crisis, with 461 closing in the first half of the year, according to Hedge Fund Research Inc. (34).

And much of this is related to speculation in energy extraction.

Speculative grade-rated energy debt has recorded a total return of minus 5.27 per cent so far this year.

As a result

Big bond investors are cutting their exposure to energy companies in the $1.3tn US market for junk-rated debt as the year ends with little sign of oil prices stabilising (35).

And that was on 3 December before the oil price fell even further. Given the level of indebtedness more selloffs and write-offs are likely to follow, as Tracy Alloway explains.

Investors have been rushing to analyse their holdings of collateralised loan obligations. CLOs are a type of bond that bundles together cash flows from loans made to highly indebted companies and then slices them according to risk.

Commercial mortgage-backed securities, which pool loans secured by commercial properties such as offices and industrial facilities, are also under scrutiny. Some 25 CMBS deals worth $251m have loans on properties in the Bakken formation of North Dakota — where shale drillers have been scaling back — according to Morgan Stanley estimates.

Pressure to identify and potentially offload energy-related debt is likely to intensify as the end of the year approaches and asset managers prepare portfolios for review by investors — a process known as window-dressing.

In short they are trying to present a picture which is brighter than it really is. In fact the inter-connectedness of the energy companies, hedge funds, private equity and institutional investors that is the stuff of modern financial capitalism suggest that we might be talking about a wider financial crisis. As Ralph Atkins put it

What might seem a local squall is spreading. As an asset class, high-yield bonds have already given up this year’s gains. The danger is of a broader shift that spills into equities and other assets (36).

The world derivative market stands at $236.8 billion of which about one sixth is in energy-related high yield bonds. The returns on these that shale was supposed to bring cannot but lead to default. How serious the consequences for wider financial disaster is a matter of debate but one thing is clear. There is no universally rosy scenario for global capitalism arising out of the oil price fall. And with the world plagued by mounting debt and minimal growth there are few options for manoeuvre amongst the imperialist powers. Saudi Arabia and its Arab followers have to stand firm on keeping up oil production and Putin cannot back down in the Ukraine. The US Congress don’t appear ready to do a nuclear deal with Iran any more than the Iranian hardliners want one. With the Middle East in turmoil we can also expect to see more of the same humanitarian catastrophe that we have seen since the Arab Spring began in 2011. Oil may now be cheaper but the continuing existence of capitalism comes at an increasingly higher price for humanity.

Jock, 14 January 2015(1) iea.org Some analysts don’t appear to accept this figure (see Brad Plumer at vox.com oil-prices-falling) and put it as low as 75 million barrels a day but the former appears to be confirmed by almost all other sources including other articles by the same Brad Plumer!

(5) If you want to buy oil now you pay the “spot” price. This is the actual price for immediate delivery and fixed on these exchanges. “Fixed” is probably the right word as the oil majors like BP and Shell have been accused of rigging the price in a cartel-type agreement. See theguardian.com

(6) There is also hedging by big oil users like airlines to ensure they guard against the very price fluctuations we are analysing but that is different from the spread-betting of the financial speculators.

(9) See leftcom.org

(10) The full list is Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela.

(15) This is from the right-wing US think tank the Cato Institute. They have an almost touching nineteenth century belief that laissez-faire capitalism can still work well even in the epoch of imperialism. Nevertheless this article is not only a useful source of information on 1973 it also underlines how imperialist policy in oil is driven more by future fears than current realities. cato.org For a more radical take on 1973 see the following video (unfortunately commentary only in French and German) youtube.com The interview with Akins is particularly revealing.

(18) See “Opec leader vows to maintain oil output even if price hits $20” in the Financial Times 23 December 2014.

(19) See Lex Column _Financial Times_24 December 2014.

(20) Figures in this section from Chris Giles “No guarantee of a magic stimulus in new low price era” _Financial Times_16 December 2014.

(21) As we go to press Rouhani accuses them of corruption (indirectly of course) and has suggested that there is a referendum on the nuclear issue to undermine the Pasdaran’s opposition.

(22) Last two figures from uk.finance.yahoo.com

(23) Sergei Guriev (Professor of Economics at Science Po Paris) “Russia is heading into an economic storm with no captain” _Financial Times_17 December 2014.

(24) Loc cit.

(25) See Jack Farchy “Primary Colours” in Financial Times 10 June 2014.

(26) "Putin ally predicts a full-blown economic crisis next year and urges improved ties with the West" Financial Times 23 December 2014.

(27) Financial Times, 19 December.

(28) See leftcom.org

(29) We are obviously not dealing here with the appalling ecological consequences of all forms of “tight oil” extraction such as shale and tar sands or even deepwater extraction. The disaster at Deepwater Horizon was just waiting to happen and will not be the last. See leftcom.org bp%E2%80%99s-deepwater-horizon-capitalism-is-the-disaster

(30) ft.com. html#axzz3N2E53AeU

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #05

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

Jock "hits the jackpot" with this remarkable article - if I may express my appreciation in words appropriate to capitalism. Such meticulous analysis; such economic insight; such grasp of bourgeois nationalistic competitive motivation. It seems that oil is king and all depends on his continual financial triumph. But overall the article points with a kind of quiet but almost an awesome inevitability to shattering economic meltdown not so far away now.

Thanks for this article. I've been reading the bourgeois financial publications in the US and they all seem to be in a state of denial that there is anything going wrong with their shale oil industry. Even though workers are being laid off throughout the entire industry supply chain. It was as if as soon as the price of oil began to drop the Wall Street Journal and other publications rushed to assure people that the good times were still going to last forever, when the lights could literally start going out in Bakken, ND.